We found 832 results that contain "experiential learning"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Spartan Studios: High-Impact Practices and Resources for Experiential Learning

Topic Area: Information Session

Presented by: Ellie Louson, Caroline Blommel, Aalayna Green, Nick Young

Abstract:

This workshop shares how instructors can design, implement, and assess experiential, interdisciplinary, and/or project-based learning in courses. This approach empowers and equips instructors to leverage high-impact practices in their own teaching. We introduce an evidence driven framework for these complex learning experiences and share stories from students and faculty about how it works from the past 3 years of the Spartan Studios project in the Hub. A key outcome of this work is our Playkit: a combination playbook and toolkit that is a resource for faculty members. In this pedagogical framework coaching was a critical feature of the success of these courses. Participants will learn the strategy of pivoting to a coaching role, the gains for student autonomy and ownership, the value of not solving students’ problems, and how students experience this new way of teaching. Another key feature of this framework is the use of reflection at multiple points throughout the course experience, benefiting both student learning and teaching approaches. Through facilitated conversations, participants will apply this framework to design their own experiential, project-based, and/or interdisciplinary courses. Participants can also implement à la carte one or more of these elements into their teaching practice without developing an entirely new experiential course and still obtain benefits for student learning outcomes. Participants should bring a syllabus or course-level topic to develop during the workshop.

Session Resources: Spartans Studio Playlist - Introduction

Presented by: Ellie Louson, Caroline Blommel, Aalayna Green, Nick Young

Abstract:

This workshop shares how instructors can design, implement, and assess experiential, interdisciplinary, and/or project-based learning in courses. This approach empowers and equips instructors to leverage high-impact practices in their own teaching. We introduce an evidence driven framework for these complex learning experiences and share stories from students and faculty about how it works from the past 3 years of the Spartan Studios project in the Hub. A key outcome of this work is our Playkit: a combination playbook and toolkit that is a resource for faculty members. In this pedagogical framework coaching was a critical feature of the success of these courses. Participants will learn the strategy of pivoting to a coaching role, the gains for student autonomy and ownership, the value of not solving students’ problems, and how students experience this new way of teaching. Another key feature of this framework is the use of reflection at multiple points throughout the course experience, benefiting both student learning and teaching approaches. Through facilitated conversations, participants will apply this framework to design their own experiential, project-based, and/or interdisciplinary courses. Participants can also implement à la carte one or more of these elements into their teaching practice without developing an entirely new experiential course and still obtain benefits for student learning outcomes. Participants should bring a syllabus or course-level topic to develop during the workshop.

Session Resources: Spartans Studio Playlist - Introduction

Authored by:

Ellie Louson, Caroline Blommel, Aalayna Green, Nick Young

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Spartan Studios: High-Impact Practices and Resources for Experiential Learning

Topic Area: Information Session

Presented by: Ellie Louson,&nb...

Presented by: Ellie Louson,&nb...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, May 3, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Making Something Out of Nothing: Experiential Learning, Digital Publishing, and Budget Cuts

The Cube (publishing - process - praxis) is a publishing nexus housed in Michigan State University's Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC). The Cube supports, promotes, and produces open-access works created by diverse members of the mid-Michigan and Michigan State communities. Our publishing focuses on messages of social justice, accessibility, diversity, and inclusion. We provide a space for diverse voices to publish and advocate for their work and engage with audiences they would otherwise have difficulty reaching. This Poster, featuring The Cube's director, its graduate assistant, and its lead undergraduate web developer, will provide an overview of the work the Cube does, from brainstorming to final product, and show how we faced adversity and thought creatively in the wake of massive budget cuts to the humanities.

To access a PDF of the "We Are The Cube" poster, click here.

Description of the Poster

This poster is made using something similar to a mind map, with bubbles named “high-impact experiential learning,” “people,” “mentorship and community,” “projects,” “process,” and “skills.” Surrounding those bubbles are smaller bubbles with descriptions (described below).

We are The Cube.

Publishing - Process - Praxis

We are a publishing nexus that supports, promotes, and produces open-access work created by diverse members of the mid-Michigan community, focusing on messages of social justice, accessibility, diversity, and inclusion through high-impact experiential learning. We provide a space for diverse ranges of persons, places, and communities to publish and advocate for their work and to engage with audiences they would otherwise be unable to reach.

High-Impact Experiential Learning Circle:

Mentorship is key. Project proposals come to The Cube via our website; from there, we review projects and hire paid undergraduate and graduate interns to complete the work. At any given time, The Cube has between twelve and twenty interns, and our entire budget is dedicated to labor.

Throughout our processes, students are mentored by faculty members, encouraged to take risks and make mistakes, praised for their good work, and given credit for that work. For a full list of our mentors and interns, see our website: https://thecubemsu.com/.

Experiential learning programs allow students to take risks, make mistakes, and learn from those mistakes in a safe and supportive environment.

There are two goals. One is to learn the specifics of a particular subject, and the other is to learn about one’s own learning process.

Experiential learning works in four stages:

concrete learning,

reflective observation,

abstract conceptualization, and

active experimentation.

All of these are key for developing both hard and soft skills, which students will need to be ethical pioneers in their fields and in their communities.

Representative People Circle:

Catherine Davis, User Experience and Design Intern

Shelby Smith, Writing and Editing Intern

Grace Houdek, Graphic Design Intern

Jaclyn Krizanic, Social Media Intern

Jeanetta Mohlke-Hill, Editorial Assistant

Emily Lin, Lead UX Designer

Mitch Carr, Graduate Assistant and Project Coordinator

Kara Headly, Former Social Media Intern

Community & Mentorship Circle:

Dr. Kate Birdsall, Director

Dr. Alexandra Hidalgo, Editor-in-Chief

Dr. Marohang Lumbu, Editor-in-Chief

The Writing Center at MSU

Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC) at MSU

Projects Circle:

The Current, digital and print magazine

JOGLTEP, academic journal

Constellations, academic journal

Agnes Films, feminist film collective

The Red Cedar review, literary journal

REO Town Reading Series Anthology, digital book

Superheroes Die in the Summer, digital book

Process Circle:

Brainstorming

Collaboration

Client Relations

Consistent Voice and Branding

UX Design and Engineering

Skills Circle:

Confidence

Editing and Writing Style Guides

Professional Development

Risk Analysis

Develop Professional Portfolio

Human Centered Design

Developmental and Copy Editing

Poster by: Dr. Kate Birdsall, Mitch Carr, and Emily Lin (Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC) Department))

To access a PDF of the "We Are The Cube" poster, click here.

Description of the Poster

This poster is made using something similar to a mind map, with bubbles named “high-impact experiential learning,” “people,” “mentorship and community,” “projects,” “process,” and “skills.” Surrounding those bubbles are smaller bubbles with descriptions (described below).

We are The Cube.

Publishing - Process - Praxis

We are a publishing nexus that supports, promotes, and produces open-access work created by diverse members of the mid-Michigan community, focusing on messages of social justice, accessibility, diversity, and inclusion through high-impact experiential learning. We provide a space for diverse ranges of persons, places, and communities to publish and advocate for their work and to engage with audiences they would otherwise be unable to reach.

High-Impact Experiential Learning Circle:

Mentorship is key. Project proposals come to The Cube via our website; from there, we review projects and hire paid undergraduate and graduate interns to complete the work. At any given time, The Cube has between twelve and twenty interns, and our entire budget is dedicated to labor.

Throughout our processes, students are mentored by faculty members, encouraged to take risks and make mistakes, praised for their good work, and given credit for that work. For a full list of our mentors and interns, see our website: https://thecubemsu.com/.

Experiential learning programs allow students to take risks, make mistakes, and learn from those mistakes in a safe and supportive environment.

There are two goals. One is to learn the specifics of a particular subject, and the other is to learn about one’s own learning process.

Experiential learning works in four stages:

concrete learning,

reflective observation,

abstract conceptualization, and

active experimentation.

All of these are key for developing both hard and soft skills, which students will need to be ethical pioneers in their fields and in their communities.

Representative People Circle:

Catherine Davis, User Experience and Design Intern

Shelby Smith, Writing and Editing Intern

Grace Houdek, Graphic Design Intern

Jaclyn Krizanic, Social Media Intern

Jeanetta Mohlke-Hill, Editorial Assistant

Emily Lin, Lead UX Designer

Mitch Carr, Graduate Assistant and Project Coordinator

Kara Headly, Former Social Media Intern

Community & Mentorship Circle:

Dr. Kate Birdsall, Director

Dr. Alexandra Hidalgo, Editor-in-Chief

Dr. Marohang Lumbu, Editor-in-Chief

The Writing Center at MSU

Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC) at MSU

Projects Circle:

The Current, digital and print magazine

JOGLTEP, academic journal

Constellations, academic journal

Agnes Films, feminist film collective

The Red Cedar review, literary journal

REO Town Reading Series Anthology, digital book

Superheroes Die in the Summer, digital book

Process Circle:

Brainstorming

Collaboration

Client Relations

Consistent Voice and Branding

UX Design and Engineering

Skills Circle:

Confidence

Editing and Writing Style Guides

Professional Development

Risk Analysis

Develop Professional Portfolio

Human Centered Design

Developmental and Copy Editing

Poster by: Dr. Kate Birdsall, Mitch Carr, and Emily Lin (Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC) Department))

Authored by:

Kate Birdsall, Mitch Carr, Emily Lin

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Making Something Out of Nothing: Experiential Learning, Digital Publishing, and Budget Cuts

The Cube (publishing - process - praxis) is a publishing nexus hous...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Monday, Apr 26, 2021

Posted on: Teaching Toolkit Tailgate

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Make Better Experiential Courses

This card describes how to make better experiential courses, the GORP model of experiential learning, and resources including how to get in touch with the Hub for Innovation to get support for your experiential activities in courses.

Authored by:

Ellie Louson and Bill Heinrich

Posted on: Teaching Toolkit Tailgate

Make Better Experiential Courses

This card describes how to make better experiential courses, the GO...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Friday, Aug 21, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Spartan Studios: GORP for High Impact Experiential Teaching

GORP for High Impact Experiential TeachingThis is the third article in our iTeach.MSU playlist for the Spartan Studios Playkit.

🔧 Earlier phases of the Studios project developed a framework for experiential learning with the acronym GORP: Gravity, Ownership, Relationship, and Place (Heinrich, Lauren, & Logan, under review). The acronym GORP stands for “good ol’ raisins and peanuts” and emerged from one of the researchers’ background in outdoor education. The GORP framework is a key aspect of how we have designed Studios courses. We have seen how its 4 elements can lead to transformational learning experiences for students in Studios courses. (Heinrich et al. 2021). We encourage you to consider how the following 4 elements of the framework might fit in your own experiential course. They aren’t all-or-nothing, and course instructors can decide in what ways to incorporate them into your course design.

▶️Gravity: Give students a challenge or opportunity that matters to them and they’ll be motivated. The primary motivator for student work in a traditional course is usually the assessment or grade. By organizing your experiential course around a significant challenge, a wicked problem, or an opportunity for students to meaningfully participate in or affect their world, you can offer students an alternative motivator: making a difference to communities affected by these challenges. A course description that includes this gravity can help attract students who are passionate about that issue. Keep gravity central as you design your course and students’ interactions with community partners. A holistic approach to grading, where students are assessed on their overall participation, processes, and reflections about their experience, helps to prevent the course grade from reasserting itself as the gravity. In other words, shift the point of gravity for students away from the grade.

▶️Ownership: Give students autonomy throughout the experiential course, from the design of their projects through their implementation. Let them manage their teams and be accountable to each other for their work. Having this ownership movitates high levels of engagement with the course material and assignments and increases participation. In a course with high ownership, students see themselves as creators and contributors to real conversations with the course’s local partners. This could even extend to giving students autonomy over elements of your course design. Include opportunities for emergent outcomes that aren’t predetermined in the course design (for example, be flexible about the kinds of projects that are within the scope of the course, or students being able to pivot their approach based on new ideas) and for students to steer the instruction.

▶️Relationship: Experiential courses give instructors the opportunity to reset the traditional teacher-student relationship. Be a coach in addition to a lecturer. You can support students’ work on their teams and be a resource for them as they solve problems that emerge during their work. This could look like instructors circulating as student teams explain their project plans and giving feedback or suggesting alternatives the students hadn’t considered. Even something as simple as putting yourself at the same literal level as your students, instead of lecturing from the front of the room, can contribute to a more even relationship. Learn from the students outside your discipline, and encourage students to learn from each other. By removing yourself as the gatekeeper of acceptable solutions, you empower students to learn from their choices. These reconfigured relationships require trust within student teams, within the team of co-instructors, and between students and faculty. And although instructors ultimately do have power over students’ evaluations, try to avoid sudden reassertions of that power which can undermine student ownership and trust. Students (and faculty!) may be uncomfortable at first with such a dramatic shift in agency; you should be explicit that this will be a different kind of learning experience. We suggest making reflection on the new relationships part of your classroom culture. Instructors should be empowered to facilitate student-driven learning while also providing the benefits of their expertise, knowledge, and judgement. We offer more advice and examples in “Coaching” below.

▶️Place: Because Studios courses connect to local needs or partners in specific places, you can focus your teaching on those places and connect them to students’ work. These places can be elsewhere on campus, in the local community, or even abroad. Visit it if you can (physically or virtually), and have students experience and reflect on their time outside the classroom. Places resonate, even if they can’t visit in-person. Encourage students to form their own connections with the place: What does it mean to them or to the community impacted by the course’s challenge? Also, think about your teaching space. Early Studios courses were held in the Hub’s flex space, a room with moveable furniture and whiteboard walls that students could reconfigure based on their teams’ needs. A flexible and collaborative mindset open to new and radical student-driven possibilities is part of the conceptual space we want to build in these courses. This flexibility and connection is also possible in virtual classrooms and workspaces. Consider the learning affordances of both physical and virtual spaces that can enhance your students’ experience.Photo by Pratik Bachhav on Unsplash

🔧 Earlier phases of the Studios project developed a framework for experiential learning with the acronym GORP: Gravity, Ownership, Relationship, and Place (Heinrich, Lauren, & Logan, under review). The acronym GORP stands for “good ol’ raisins and peanuts” and emerged from one of the researchers’ background in outdoor education. The GORP framework is a key aspect of how we have designed Studios courses. We have seen how its 4 elements can lead to transformational learning experiences for students in Studios courses. (Heinrich et al. 2021). We encourage you to consider how the following 4 elements of the framework might fit in your own experiential course. They aren’t all-or-nothing, and course instructors can decide in what ways to incorporate them into your course design.

▶️Gravity: Give students a challenge or opportunity that matters to them and they’ll be motivated. The primary motivator for student work in a traditional course is usually the assessment or grade. By organizing your experiential course around a significant challenge, a wicked problem, or an opportunity for students to meaningfully participate in or affect their world, you can offer students an alternative motivator: making a difference to communities affected by these challenges. A course description that includes this gravity can help attract students who are passionate about that issue. Keep gravity central as you design your course and students’ interactions with community partners. A holistic approach to grading, where students are assessed on their overall participation, processes, and reflections about their experience, helps to prevent the course grade from reasserting itself as the gravity. In other words, shift the point of gravity for students away from the grade.

▶️Ownership: Give students autonomy throughout the experiential course, from the design of their projects through their implementation. Let them manage their teams and be accountable to each other for their work. Having this ownership movitates high levels of engagement with the course material and assignments and increases participation. In a course with high ownership, students see themselves as creators and contributors to real conversations with the course’s local partners. This could even extend to giving students autonomy over elements of your course design. Include opportunities for emergent outcomes that aren’t predetermined in the course design (for example, be flexible about the kinds of projects that are within the scope of the course, or students being able to pivot their approach based on new ideas) and for students to steer the instruction.

▶️Relationship: Experiential courses give instructors the opportunity to reset the traditional teacher-student relationship. Be a coach in addition to a lecturer. You can support students’ work on their teams and be a resource for them as they solve problems that emerge during their work. This could look like instructors circulating as student teams explain their project plans and giving feedback or suggesting alternatives the students hadn’t considered. Even something as simple as putting yourself at the same literal level as your students, instead of lecturing from the front of the room, can contribute to a more even relationship. Learn from the students outside your discipline, and encourage students to learn from each other. By removing yourself as the gatekeeper of acceptable solutions, you empower students to learn from their choices. These reconfigured relationships require trust within student teams, within the team of co-instructors, and between students and faculty. And although instructors ultimately do have power over students’ evaluations, try to avoid sudden reassertions of that power which can undermine student ownership and trust. Students (and faculty!) may be uncomfortable at first with such a dramatic shift in agency; you should be explicit that this will be a different kind of learning experience. We suggest making reflection on the new relationships part of your classroom culture. Instructors should be empowered to facilitate student-driven learning while also providing the benefits of their expertise, knowledge, and judgement. We offer more advice and examples in “Coaching” below.

▶️Place: Because Studios courses connect to local needs or partners in specific places, you can focus your teaching on those places and connect them to students’ work. These places can be elsewhere on campus, in the local community, or even abroad. Visit it if you can (physically or virtually), and have students experience and reflect on their time outside the classroom. Places resonate, even if they can’t visit in-person. Encourage students to form their own connections with the place: What does it mean to them or to the community impacted by the course’s challenge? Also, think about your teaching space. Early Studios courses were held in the Hub’s flex space, a room with moveable furniture and whiteboard walls that students could reconfigure based on their teams’ needs. A flexible and collaborative mindset open to new and radical student-driven possibilities is part of the conceptual space we want to build in these courses. This flexibility and connection is also possible in virtual classrooms and workspaces. Consider the learning affordances of both physical and virtual spaces that can enhance your students’ experience.Photo by Pratik Bachhav on Unsplash

Authored by:

Ellie Louson

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Spartan Studios: GORP for High Impact Experiential Teaching

GORP for High Impact Experiential TeachingThis is the third article...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

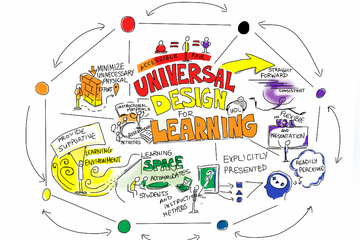

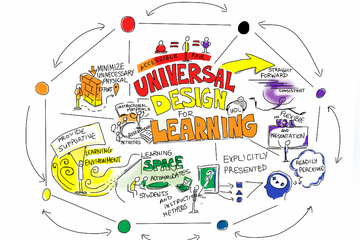

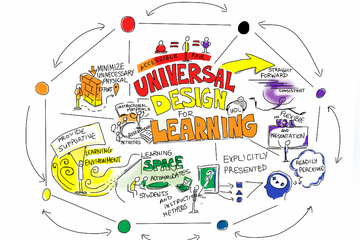

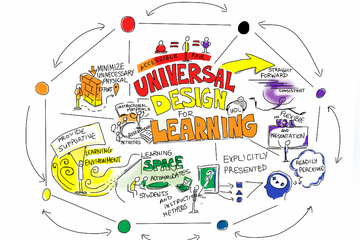

Universal Design for Learning

What is Universal Design for Learning?

According to the CAST website, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is “a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn.” Although UDL is not exclusive to digital accessibility, this framework prioritizes inclusivity and thus inherently lends itself to the creation of courses that are accessible to all students.

UDL is built on an understanding of the term learning as the interaction and layering of:

Recognition, or the “what”

Skills and Strategies, or the “how”

Caring and Prioritizing, or the “why”

The ultimate goal of UDL is to design a course that is accessible to everyone from its very inception and is open to flexibility. UDL can help instructors create accessible goals, methods, materials, and assessments.

UDL proposes the following three principles to upend barriers to learning:

Representation - present material in a variety of ways

Action and Expression - allow students to share what they know in their own

Engagement - provide students with choices

Explore this topic further in CAST’s “UDL at a Glance”:

UDL GuidelinesLearn more about the Guildlines for UDL via the accessible and interactive table on the CAST website.

Instructional Technology and Development’s Incorporating Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into Your Course Design

Further Reading

Michigan Tech’s guide for UDL

Weaver Library’s Research Guide Universal Design for Learning (UDL) & Accessibility for Faculty

Introduction to Universal Learning Design (UDL) by Shannon Kelly

Sources

About universal design for learning. CAST. (2024, March 28). https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

This article is part of the Digital Accessibility Toolkit.

According to the CAST website, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is “a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn.” Although UDL is not exclusive to digital accessibility, this framework prioritizes inclusivity and thus inherently lends itself to the creation of courses that are accessible to all students.

UDL is built on an understanding of the term learning as the interaction and layering of:

Recognition, or the “what”

Skills and Strategies, or the “how”

Caring and Prioritizing, or the “why”

The ultimate goal of UDL is to design a course that is accessible to everyone from its very inception and is open to flexibility. UDL can help instructors create accessible goals, methods, materials, and assessments.

UDL proposes the following three principles to upend barriers to learning:

Representation - present material in a variety of ways

Action and Expression - allow students to share what they know in their own

Engagement - provide students with choices

Explore this topic further in CAST’s “UDL at a Glance”:

UDL GuidelinesLearn more about the Guildlines for UDL via the accessible and interactive table on the CAST website.

Instructional Technology and Development’s Incorporating Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into Your Course Design

Further Reading

Michigan Tech’s guide for UDL

Weaver Library’s Research Guide Universal Design for Learning (UDL) & Accessibility for Faculty

Introduction to Universal Learning Design (UDL) by Shannon Kelly

Sources

About universal design for learning. CAST. (2024, March 28). https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

This article is part of the Digital Accessibility Toolkit.

Posted by:

Katherine Knowles

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Universal Design for Learning

What is Universal Design for Learning?

According to the CAST websit...

According to the CAST websit...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, Apr 24, 2024

Posted on: #iteachmsu

ASSESSING LEARNING

Harmonizing Department and University Level Learning Outcomes and Evaluating Learning Goals

Topic Area: DEI

Presented by: Raphael Auras, Laura Bix, Cimberly Weir

Abstract:

The class learning outcomes (CLO) of the packaging bachelor’s degree at the School of Packaging (SoP) at Michigan State University (MSU) were mapped to competency-based, programmatic learning outcomes (CPLO), which are aligned with the broad learning goals of the University (MSU-LG). Six CPLOs were developed using group consensus building for the core curriculum: CPLO-1: Evaluate packaging systems; CPLO-2: Analyze tradeoffs in packaging systems; CPLO-3: Design innovative and sustainable packaging systems; CPLO-4: Manage projects in diverse teams; CPLO-5: Communicate effectively considering diverse audiences; CPLO-6: Professional and ethical manner. Relationships, from specific to broad, (CLOs to CPLOs to MSU-LG) were mapped during several group sessions with SoP packaging educators utilizing the same consensus-building process. This mapping scheme (class-specific CLOs supporting broader program CPLOs and, ultimately, MSU-LGs) was developed to guarantee alignment of expectations for learning from the course to the packaging program to the University level.Since 2018, assessment tools, including rubrics, questionnaires, and activity/assignments intended to evaluate learning were developed to evaluate core and elective courses offered by the SoP. Data collection of each student’s performance in the core and selective elective courses was conducted and assessed utilizing Watermark’s VIA software.

Assessment of student performance related to each of the CLOs and related CPLO and MSU-LG provided objective evidence of learning across the SoP curriculum as well as how CLOs, delivered and assessed at the individual student level, translate into competence achieved at the programmatic and university levels. As more instruments were implemented to assess students’ performance, areas of improvement became increasingly evident and a path forward for curriculum adjustment and development manifested.

Presented by: Raphael Auras, Laura Bix, Cimberly Weir

Abstract:

The class learning outcomes (CLO) of the packaging bachelor’s degree at the School of Packaging (SoP) at Michigan State University (MSU) were mapped to competency-based, programmatic learning outcomes (CPLO), which are aligned with the broad learning goals of the University (MSU-LG). Six CPLOs were developed using group consensus building for the core curriculum: CPLO-1: Evaluate packaging systems; CPLO-2: Analyze tradeoffs in packaging systems; CPLO-3: Design innovative and sustainable packaging systems; CPLO-4: Manage projects in diverse teams; CPLO-5: Communicate effectively considering diverse audiences; CPLO-6: Professional and ethical manner. Relationships, from specific to broad, (CLOs to CPLOs to MSU-LG) were mapped during several group sessions with SoP packaging educators utilizing the same consensus-building process. This mapping scheme (class-specific CLOs supporting broader program CPLOs and, ultimately, MSU-LGs) was developed to guarantee alignment of expectations for learning from the course to the packaging program to the University level.Since 2018, assessment tools, including rubrics, questionnaires, and activity/assignments intended to evaluate learning were developed to evaluate core and elective courses offered by the SoP. Data collection of each student’s performance in the core and selective elective courses was conducted and assessed utilizing Watermark’s VIA software.

Assessment of student performance related to each of the CLOs and related CPLO and MSU-LG provided objective evidence of learning across the SoP curriculum as well as how CLOs, delivered and assessed at the individual student level, translate into competence achieved at the programmatic and university levels. As more instruments were implemented to assess students’ performance, areas of improvement became increasingly evident and a path forward for curriculum adjustment and development manifested.

Authored by:

Raphael Auras, Laura Bix, Cimberly Weir

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Harmonizing Department and University Level Learning Outcomes and Evaluating Learning Goals

Topic Area: DEI

Presented by: Raphael Auras, Laura Bix,&n...

Presented by: Raphael Auras, Laura Bix,&n...

Authored by:

ASSESSING LEARNING

Wednesday, Apr 28, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Planning for Cooperative Learning

Picture a classroom full of voices, chairs facing not the front but one another, heads leaned close, and pens moving furiously. This image is very different from the traditional university classroom in which a gallery of students listen and watch as a professor recites information. However, an increasing amount of university instructors favor the former example for their classrooms (Smith et al. 2005). Why would undergraduate instructors turn away from tradition and toward this more cooperative learning environment?

Many studies have found there is a fundamental difference in the way students engage with material in cooperative classes. In my personal experience with cooperative learning, I have witnessed students constructing new knowledge based on previous experience, gaining a richer understanding of a concept by explaining it to a peer, and even voicing their insecurities with the material. In this post, I will discuss the benefits of cooperative learning and explore some cooperative learning approaches. I hope to persuade you that cooperative learning is an effective and feasible approach that can be incorporated into your classroom this semester and beyond.

Active Learning vs. Lecturing

Anecdotal evidence aside, the data speak for themselves. In a meta-analysis of over 200 studies, Freedman et al. (2014) found dramatic differences between lecture-based and active instructional strategies (including cooperative learning) in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) classrooms. Students in active learning classrooms are 1.5 times less likely to fail than students in lecture-based classrooms and outperform their counterparts on exams by an average of 6%. These results point to increased retention and higher GPAs of students within the discipline when active learning strategies are implemented.

What drives these increased learning gains? In the transition between lecturing and active learning, the instructor shifts the learning environment from being teacher-centered to student-centered. This shift in focus promotes greater accountability, ownership of ideas, a sense of belonging amongst students, and a more cooperative classroom.

The Cooperative Classroom

Cooperative learning is one active learning approach documented as effective in achieving student learning goals. With a cooperative learning approach, students work together in small groups to accomplish tasks that promote positive interdependence. In other words, learning activities are structured so that achievement is both beneficial to individual students and also to the group as a whole. These activities can last anywhere from five minutes to an entire semester. Successful cooperative learning strategies promote student engagement with the material, individual accountability, and teamwork-building skills. Cooperative learning also promotes regular, formative assessment of student learning, higher order thinking, and builds classroom community (see Smith et al. 2005),

Cooperative Learning in Action

The key to successfully implementing cooperative learning is aligning it with learning objectives. Cooperative learning activities aren’t extras, but essential steps toward optimal learning. Some topics could include concepts that will be emphasized on the exam, big ideas for the day, and items that are difficult for students to master. The better integrated these activities are, the easier it will be to select approaches that meet your overall course objectives.

It may seem like an intimidating task to implement cooperative learning in a lecture-based course. Completely redesigning a course involves significant time and effort, and graduate student assistants often don’t have the freedom to dictate the classroom structure. The good news is that cooperative learning can be incorporated into courses in small, low-stakes ways. The following are three strategies that can be integrated into your curriculum next semester and accomplished within 5-15 minutes. I would suggest starting here:

Think-pair-share

Instructors pose a question or discussion topic (e.g., “Based on what you know about global wind and ocean currents, describe why the wave height in the Southern Ocean is an average of two meters higher than in the Equatorial Pacific”). Instructors then give students individual reflection time to process the question and to think about their answer. Following this silent period, students are then asked to pair up with another student to discuss their answer and to resolve any differences (if there is a correct answer to the question). The class can then come together as a large group once again, and the instructor can call on individual groups to share their discussions. This approach encourages students to explore and demonstrate their understanding of key concepts prior to a high-stakes exam in a way that is not possible in a lecture format.

Bonus: The pair step is a great opportunity for the instructor to walk throughout the room to monitor the discussion groups and connect with students on a more individual basis. The share step can be used to assess the distribution of ideas among students and identify sticky points that may require additional attention. This approach also allows students to speak up in class after vetting their thoughts with another student, which helps to decrease public speaking anxiety.

Minute Paper

Similarly to the think-pair-share activity, instructors pose a question or discussion topic. Instructors then provide time (typically under three minutes) for students to write down their ideas . This could be specified as anything from a “brain dump” (e.g., “Discuss the factors that dictate the growth of algae in the Arctic Ocean”) to a more structured form (“e.g., How would you design an experiment to measure the effect of temperature and light on algal growth in the Arctic Ocean?”). Students can then team up into small groups to discuss their answers and come to a consensus or perspective on the major ideas from the question. Following small group time, a few groups can be asked to report out to the whole class about their discussion. The minute paper approach allows instructors and students to move beyond memorization and into higher order thinking skills such as analysis and evaluation.

Bonus: Positive interdependence can be achieved by assigning group members specific roles (e.g., recorder, checker, task manager, and spokesperson). These roles can be rotated each time the activity is used to allow students to practice each communication skill.

Jigsaw

This learning strategy works well for course concepts that can be split up into separate yet interconnected parts. Each part thus represents a piece of the puzzle, and the complete puzzle requires each individual piece to be complete. The jigsaw approach is split into two steps: the expert group meeting and the jigsaw group meeting. In the expert group meeting, instructors split students into small groups that are each assigned one part of the relevant content. Expert groups are assigned to discuss their “puzzle piece” and to achieve a consensus or mastery of their component. Expert groups are then dissolved and new jigsaw groups are formed, made up of one person from each expert group. In the jigsaw group meeting, each “expert ambassador” has a chance to report to the group about his or her piece of the puzzle. Jigsaw groups are then assigned the task of connecting each component to form a complete picture of the concept. The jigsaw approach encourages students to take ownership of their component of the concept and improve their communication skills when meeting with the jigsaw group.

Bonus: Keep in mind that this method, while rich in discussion opportunities, requires the most logistical planning and organizational support of the three strategies outlined. For further reading, see https://www.jigsaw.org.

What are your favorite cooperative learning activities that you use in your own classroom? Do you have a successful strategy to encourage students to embrace cooperative learning? Please share your thoughts in the comments below or use the hashtag #ITeachMSU to further engage in the conversation on Twitter or Facebook.

Additional Reading

Angelo, T., K.P. Cross. 1993. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. Jossey-Bass. ISBN: 1555425003. http://www.amazon.com/Classroom-Assessment-Techniques-Handbook-Teachers/dp/155425003/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1450279809&sr=8-1&keywords=classroom+assesment+techniques

Freedman, S., S.L. Eddy, M. McDonough, M.K. Smith, N. Okoroafor, H. Jordt, and M.P. Wenderoth. 2014. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111(23): 8410-8415. http://www.pnas.org/content/111/23/8410.full.pdf

Johnson D.W., R.T. Johnson, and K.A. Smith. 2006. Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom. Interaction Book Co. ISBN: 978-0939603145. http://www.amazon.com/Active-Learning-Cooperation-College-Classroom/dp/093960314

Smith, K.A., S.D. Sheppard, D.W. Johnson, and R.T. Johnson. 2005. Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-based practices (cooperative learning and problem-based learning). Journal of Engineering Education 94: 87-101.http://personal.cege.umn.edu/~smith/docs/Smith-Pedagogies_of_Engagement.pdf

Originally posted at “Inside Teaching MSU” (site no longer live): Salk, K. Planning for Cooperative Learning. inside teaching.grad.msu.edu

Many studies have found there is a fundamental difference in the way students engage with material in cooperative classes. In my personal experience with cooperative learning, I have witnessed students constructing new knowledge based on previous experience, gaining a richer understanding of a concept by explaining it to a peer, and even voicing their insecurities with the material. In this post, I will discuss the benefits of cooperative learning and explore some cooperative learning approaches. I hope to persuade you that cooperative learning is an effective and feasible approach that can be incorporated into your classroom this semester and beyond.

Active Learning vs. Lecturing

Anecdotal evidence aside, the data speak for themselves. In a meta-analysis of over 200 studies, Freedman et al. (2014) found dramatic differences between lecture-based and active instructional strategies (including cooperative learning) in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) classrooms. Students in active learning classrooms are 1.5 times less likely to fail than students in lecture-based classrooms and outperform their counterparts on exams by an average of 6%. These results point to increased retention and higher GPAs of students within the discipline when active learning strategies are implemented.

What drives these increased learning gains? In the transition between lecturing and active learning, the instructor shifts the learning environment from being teacher-centered to student-centered. This shift in focus promotes greater accountability, ownership of ideas, a sense of belonging amongst students, and a more cooperative classroom.

The Cooperative Classroom

Cooperative learning is one active learning approach documented as effective in achieving student learning goals. With a cooperative learning approach, students work together in small groups to accomplish tasks that promote positive interdependence. In other words, learning activities are structured so that achievement is both beneficial to individual students and also to the group as a whole. These activities can last anywhere from five minutes to an entire semester. Successful cooperative learning strategies promote student engagement with the material, individual accountability, and teamwork-building skills. Cooperative learning also promotes regular, formative assessment of student learning, higher order thinking, and builds classroom community (see Smith et al. 2005),

Cooperative Learning in Action

The key to successfully implementing cooperative learning is aligning it with learning objectives. Cooperative learning activities aren’t extras, but essential steps toward optimal learning. Some topics could include concepts that will be emphasized on the exam, big ideas for the day, and items that are difficult for students to master. The better integrated these activities are, the easier it will be to select approaches that meet your overall course objectives.

It may seem like an intimidating task to implement cooperative learning in a lecture-based course. Completely redesigning a course involves significant time and effort, and graduate student assistants often don’t have the freedom to dictate the classroom structure. The good news is that cooperative learning can be incorporated into courses in small, low-stakes ways. The following are three strategies that can be integrated into your curriculum next semester and accomplished within 5-15 minutes. I would suggest starting here:

Think-pair-share

Instructors pose a question or discussion topic (e.g., “Based on what you know about global wind and ocean currents, describe why the wave height in the Southern Ocean is an average of two meters higher than in the Equatorial Pacific”). Instructors then give students individual reflection time to process the question and to think about their answer. Following this silent period, students are then asked to pair up with another student to discuss their answer and to resolve any differences (if there is a correct answer to the question). The class can then come together as a large group once again, and the instructor can call on individual groups to share their discussions. This approach encourages students to explore and demonstrate their understanding of key concepts prior to a high-stakes exam in a way that is not possible in a lecture format.

Bonus: The pair step is a great opportunity for the instructor to walk throughout the room to monitor the discussion groups and connect with students on a more individual basis. The share step can be used to assess the distribution of ideas among students and identify sticky points that may require additional attention. This approach also allows students to speak up in class after vetting their thoughts with another student, which helps to decrease public speaking anxiety.

Minute Paper

Similarly to the think-pair-share activity, instructors pose a question or discussion topic. Instructors then provide time (typically under three minutes) for students to write down their ideas . This could be specified as anything from a “brain dump” (e.g., “Discuss the factors that dictate the growth of algae in the Arctic Ocean”) to a more structured form (“e.g., How would you design an experiment to measure the effect of temperature and light on algal growth in the Arctic Ocean?”). Students can then team up into small groups to discuss their answers and come to a consensus or perspective on the major ideas from the question. Following small group time, a few groups can be asked to report out to the whole class about their discussion. The minute paper approach allows instructors and students to move beyond memorization and into higher order thinking skills such as analysis and evaluation.

Bonus: Positive interdependence can be achieved by assigning group members specific roles (e.g., recorder, checker, task manager, and spokesperson). These roles can be rotated each time the activity is used to allow students to practice each communication skill.

Jigsaw

This learning strategy works well for course concepts that can be split up into separate yet interconnected parts. Each part thus represents a piece of the puzzle, and the complete puzzle requires each individual piece to be complete. The jigsaw approach is split into two steps: the expert group meeting and the jigsaw group meeting. In the expert group meeting, instructors split students into small groups that are each assigned one part of the relevant content. Expert groups are assigned to discuss their “puzzle piece” and to achieve a consensus or mastery of their component. Expert groups are then dissolved and new jigsaw groups are formed, made up of one person from each expert group. In the jigsaw group meeting, each “expert ambassador” has a chance to report to the group about his or her piece of the puzzle. Jigsaw groups are then assigned the task of connecting each component to form a complete picture of the concept. The jigsaw approach encourages students to take ownership of their component of the concept and improve their communication skills when meeting with the jigsaw group.

Bonus: Keep in mind that this method, while rich in discussion opportunities, requires the most logistical planning and organizational support of the three strategies outlined. For further reading, see https://www.jigsaw.org.

What are your favorite cooperative learning activities that you use in your own classroom? Do you have a successful strategy to encourage students to embrace cooperative learning? Please share your thoughts in the comments below or use the hashtag #ITeachMSU to further engage in the conversation on Twitter or Facebook.

Additional Reading

Angelo, T., K.P. Cross. 1993. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. Jossey-Bass. ISBN: 1555425003. http://www.amazon.com/Classroom-Assessment-Techniques-Handbook-Teachers/dp/155425003/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1450279809&sr=8-1&keywords=classroom+assesment+techniques

Freedman, S., S.L. Eddy, M. McDonough, M.K. Smith, N. Okoroafor, H. Jordt, and M.P. Wenderoth. 2014. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111(23): 8410-8415. http://www.pnas.org/content/111/23/8410.full.pdf

Johnson D.W., R.T. Johnson, and K.A. Smith. 2006. Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom. Interaction Book Co. ISBN: 978-0939603145. http://www.amazon.com/Active-Learning-Cooperation-College-Classroom/dp/093960314

Smith, K.A., S.D. Sheppard, D.W. Johnson, and R.T. Johnson. 2005. Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-based practices (cooperative learning and problem-based learning). Journal of Engineering Education 94: 87-101.http://personal.cege.umn.edu/~smith/docs/Smith-Pedagogies_of_Engagement.pdf

Originally posted at “Inside Teaching MSU” (site no longer live): Salk, K. Planning for Cooperative Learning. inside teaching.grad.msu.edu

Posted by:

Maddie Shellgren

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Planning for Cooperative Learning

Picture a classroom full of voices, chairs facing not the front but...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Friday, Nov 2, 2018

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

MSU Learning Communities are Spaces to Explore Ideas in Education, Teaching, and Learning

"Being a part of the Learning Communities at MSU has been a wonderful experience. Within our community we have had the opportunity to share ideas, brainstorm solutions to challenges commonly faced, and expand our thinking with individuals from a wide variety of departments. I have deeply appreciated being a part of this new campus-wide community and having a space to connect with faculty and academic staff in similar positions to my own. Seeing what the other Learning Communities are doing has helped with inspiration for our own progress," said Mary-Anne Reid co-facilitator of the Sharing Process Improvement Tools in Undergraduate Internships and Experiential Education Learning Community.

Learning Communities are self-organized, safe, and supportive spaces for faculty and academic staff to address complicated questions of curriculum and pedagogy. Michigan State University has supported these initiatives since 2004 and continues to do so through a funding program administered by the Academic Advancement Network in collaboration with the Hub for Innovation in Learning and Technology.

See what Learning Communities are available

Different Aims, Different Practices

Dr. Michael Lockett, the program Director, is quick to point out that the word “safe” is crucial to that statement of purpose, as it conveys the agency members and facilitators of Learning Communities enjoy.

“Once a community is funded, our interventions in their work only take place at the most basic administrative level,” says Lockett. “It’s a space we designed to maximize autonomy and academic freedom.”

Learning Communities at MSU are free to propose their own topics and determine the structures that best support their interests. Accordingly, communities tend to vary greatly in their practices and topics. All communities, however, share three things in common: they meet at least eight times across the academic year, explore important educational themes, and welcome all members of MSU’s instructional staff, regardless of rank or discipline.

“We have approximately thirty communities running. That means approximately three hundred faculty members are contributing to and benefitting from the program. Given that scale, there’s tremendous diversity in terms of topics and methods,” says Lockett. “Broadly defined, the conversations all connect back to ideas of education, teaching, and learning, but not necessarily in a formalized curricular context. We don’t limit their purview to credit-bearing courses at MSU and some communities are invested in educational topics that transcend this campus, or this country, or even this era.”

Dialogues Characterized by Freedom and Safety

Although many Learning Communities do not discuss fraught topics, some do. “Because some groups explore topics related to critical pedagogy, they may require particular community structures,” says Lockett. “Which is to say the community is not closed but carefully defined. All communities are inclusive. But the facilitators (those members responsible for the administration and protocol within the Community) determine the structure and it’s fair for them to ask their membership to commit to certain protocols.”

Some Communities only meet the required eight times during the academic year and encourage members to drop in or out at their discretion. Other Communities are working on highly complex questions of critical pedagogy, and require regular attendance, as the associated dialogues must be sustained and reflected upon. Ultimately, the facilitators decide the protocols for each Community.

The conversations held in the Learning Communities might also involve very personal pedagogical experiences; those kinds of conversations require time, trust, and a sense of open inquiry to make the dialogue supportive and generative. The AAN strives to provide that atmosphere by respecting the autonomy of the facilitators and working diligently behind the scenes to design flexible administrative structures that can support diverse methods. Lockett says, “although it’s not necessarily their primary role, Learning Communities can be therapeutic spaces. There’s an emotional dimension to teaching, particularly in high-pressure contexts. These communities can become a place where people find support, where they can share and hopefully resolve some of the challenges they’re encountering, teacher-to-teacher.”

Why Learning Communities?

Variations on the Learning Communities program exist on many campuses. “Questions of curriculum and pedagogy are always complicated and often best addressed face-to-face,” says Lockett. “You can do a lot of important work through dialogue. When colleagues get together to discuss curriculum and pedagogy, their conversations become nuanced and empathetic and situated in a way they can’t through other discursive forms. They can also be highly creative and generative places where good ideas disseminate swiftly.”

Getting Involved

The Learning Communities at MSU grew over 150% last year, from 12 to 30 groups. Lockett credits the passion of the facilitators and the leadership of Drs. Grabill and Austin (Associate Provost for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, and Interim Associate Provost for Academic Staff Development, respectively). He also applauds the work of his predecessor, Dr. Patricia Stewart, who advocated for the program’s continued existence and provided a vision of success. “We wouldn’t be seeing this level of engagement and success without Patti’s leadership and dedication to the program,” he says.

A full list of Learning Communities and the contact information of their facilitators is available below and on the Academic Advancement Network website, in addition to information on proposing new communities.

"As a co-facilitator of the ANS TLC the past few years, I have been impressed with our cohort’s desire to continue to become better educators. Our learning community focuses on presenting and supplying tools to our members that address their reported concerns of education, including but limited to instruction, assessment, and student engagement. Since the pandemic has rendered our instruction to be “survival mode”, the ANS TLC has reached out to provide tips and tricks to its members for better classroom experiences, in whatever platform is being used. We look forward to hosting monthly “Chitter-chatter What’s the Matter” discussions alongside our continual scaffolding of the ANS curriculum for the Fall 2020 semester." said Tasia Taxis, co-facilitator of the Department of Animal Science Teaching and Learning Community (ANS TLC) Learning Community.

Learning Communities are self-organized, safe, and supportive spaces for faculty and academic staff to address complicated questions of curriculum and pedagogy. Michigan State University has supported these initiatives since 2004 and continues to do so through a funding program administered by the Academic Advancement Network in collaboration with the Hub for Innovation in Learning and Technology.

See what Learning Communities are available

Different Aims, Different Practices

Dr. Michael Lockett, the program Director, is quick to point out that the word “safe” is crucial to that statement of purpose, as it conveys the agency members and facilitators of Learning Communities enjoy.

“Once a community is funded, our interventions in their work only take place at the most basic administrative level,” says Lockett. “It’s a space we designed to maximize autonomy and academic freedom.”

Learning Communities at MSU are free to propose their own topics and determine the structures that best support their interests. Accordingly, communities tend to vary greatly in their practices and topics. All communities, however, share three things in common: they meet at least eight times across the academic year, explore important educational themes, and welcome all members of MSU’s instructional staff, regardless of rank or discipline.

“We have approximately thirty communities running. That means approximately three hundred faculty members are contributing to and benefitting from the program. Given that scale, there’s tremendous diversity in terms of topics and methods,” says Lockett. “Broadly defined, the conversations all connect back to ideas of education, teaching, and learning, but not necessarily in a formalized curricular context. We don’t limit their purview to credit-bearing courses at MSU and some communities are invested in educational topics that transcend this campus, or this country, or even this era.”

Dialogues Characterized by Freedom and Safety

Although many Learning Communities do not discuss fraught topics, some do. “Because some groups explore topics related to critical pedagogy, they may require particular community structures,” says Lockett. “Which is to say the community is not closed but carefully defined. All communities are inclusive. But the facilitators (those members responsible for the administration and protocol within the Community) determine the structure and it’s fair for them to ask their membership to commit to certain protocols.”

Some Communities only meet the required eight times during the academic year and encourage members to drop in or out at their discretion. Other Communities are working on highly complex questions of critical pedagogy, and require regular attendance, as the associated dialogues must be sustained and reflected upon. Ultimately, the facilitators decide the protocols for each Community.

The conversations held in the Learning Communities might also involve very personal pedagogical experiences; those kinds of conversations require time, trust, and a sense of open inquiry to make the dialogue supportive and generative. The AAN strives to provide that atmosphere by respecting the autonomy of the facilitators and working diligently behind the scenes to design flexible administrative structures that can support diverse methods. Lockett says, “although it’s not necessarily their primary role, Learning Communities can be therapeutic spaces. There’s an emotional dimension to teaching, particularly in high-pressure contexts. These communities can become a place where people find support, where they can share and hopefully resolve some of the challenges they’re encountering, teacher-to-teacher.”

Why Learning Communities?

Variations on the Learning Communities program exist on many campuses. “Questions of curriculum and pedagogy are always complicated and often best addressed face-to-face,” says Lockett. “You can do a lot of important work through dialogue. When colleagues get together to discuss curriculum and pedagogy, their conversations become nuanced and empathetic and situated in a way they can’t through other discursive forms. They can also be highly creative and generative places where good ideas disseminate swiftly.”

Getting Involved

The Learning Communities at MSU grew over 150% last year, from 12 to 30 groups. Lockett credits the passion of the facilitators and the leadership of Drs. Grabill and Austin (Associate Provost for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, and Interim Associate Provost for Academic Staff Development, respectively). He also applauds the work of his predecessor, Dr. Patricia Stewart, who advocated for the program’s continued existence and provided a vision of success. “We wouldn’t be seeing this level of engagement and success without Patti’s leadership and dedication to the program,” he says.

A full list of Learning Communities and the contact information of their facilitators is available below and on the Academic Advancement Network website, in addition to information on proposing new communities.

"As a co-facilitator of the ANS TLC the past few years, I have been impressed with our cohort’s desire to continue to become better educators. Our learning community focuses on presenting and supplying tools to our members that address their reported concerns of education, including but limited to instruction, assessment, and student engagement. Since the pandemic has rendered our instruction to be “survival mode”, the ANS TLC has reached out to provide tips and tricks to its members for better classroom experiences, in whatever platform is being used. We look forward to hosting monthly “Chitter-chatter What’s the Matter” discussions alongside our continual scaffolding of the ANS curriculum for the Fall 2020 semester." said Tasia Taxis, co-facilitator of the Department of Animal Science Teaching and Learning Community (ANS TLC) Learning Community.

Authored by:

Gregory Teachout

Posted on: #iteachmsu

MSU Learning Communities are Spaces to Explore Ideas in Education, Teaching, and Learning

"Being a part of the Learning Communities at MSU has been a wonderf...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Friday, Aug 20, 2021