We found 174 results that contain "inclusivity"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Lessons Learned Launching a University-Wide Initiative in a Remote Environment

In Fall 2020, the My Spartan Story team launched campus-wide My Spartan Story and the Spartan Experience Record, MSU's new co-curricular record. This session will explore successes and challenges in launching a new initiative during the pandemic, and will also explore introductory data on how we have been able to expand recognition of co-curricular learning and engagement of undergraduate Spartans.To access a PDF of the "Lessons Learned Launching a University-Wide Initiative in a Remote Environment" poster, click here.Description of the Poster

Lessons Learned Launching a Campus-Wide Initiative in a Remote Environment Poster Outline

Introduction

My Spartan Story, Michigan State University’s new co-curricular record, planned to launch to undergraduate Spartans and the MSU community in a traditional campus environment for the 2020-2021 academic year. Significant strategy, resources, and collaboration defined a launch that soon became incongruent to the campuses needs pivoting to remote learning. The My Spartan Story Team shifted strategy to solely virtual methods to grow awareness and education of My Spartan Story and the Spartan Experience Record (a new customizable record displaying learning in non-credit bearing experiences that can be requested alongside the transcript through the Registrar’s Office). Several tactics planned had to be eliminated, and communications and programming methods rethought. Thankfully, time spent investing in website updates, resources and guides, and other methods simply became more invaluable.

Methods

All

Email communications sent to faculty, staff, administrators, and undergraduate students co-created with Provost Communications Team.

Downloadable resources and guides created to assist with workflows and utilization of the My Spartan Story platform.

Faculty/Staff

Strategic outreach to campus community, presenting at unit meetings, and large monthly meetings such as Undergraduate Assistant/Associate Deans and Directors of Undergraduate Affairs (UGAAD).

My Spartan Story Faculty/Staff Workshops held 2-3 times monthly, welcoming organic connection to My Spartan Story.

Students

Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter accounts created; posts organized through Hootsuite. Content regularly shared by campus colleagues and students.

My Spartan Story 101 Workshops offered as well as Registered Student Organization Workshops in partnership with MSU Student Life.

My Spartan Story Week held in collaboration with platform partners Undergraduate Research and Center for Community Engaged Learning.

Contests and giveaways promoting engagement with the My Spartan Story platform held throughout the year.

Regular emails sent to students with a validated position on their Spartan Experience Record.

Virtual attendance at events such as Sparticipation and Spartan Remix.

Results

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Successes

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Challenges

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Future Steps

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Figure Descriptions

Position increase chart

3,556: Potential students who can have a validated position on their record by end of 2020-2021 academic year from Fall 2020 submissions

Social media platforms have significantly driven student engagement, specifically tagging students and organizations in posts.

Colleges & Divisions with Opportunities in My Spartan Story as of Fall 2020

Associate Provost for Teaching, Learning and Technology

Associate Provost for Undergraduate Education

Associate Provost for University Outreach & Engagement

College of Agriculture & Natural Resources

College of Arts & Letters

College of Communication Arts & Sciences

College of Education

College of Engineering

College of Natural Science

College of Osteopathic Medicine

College of Social Science

Division of Residential & Hospitality Services

Eli Broad College of Business

Executive Vice President for Administration

Honors College

International Studies & Programs

James Madison College

Libraries

Office of Civil Rights & Title IX Education & Compliance

Provost & Academic Affairs

Vice President for Research & Graduate Studies

Vice President for Student Affairs & Services

Lessons Learned Launching a Campus-Wide Initiative in a Remote Environment Poster Outline

Introduction

My Spartan Story, Michigan State University’s new co-curricular record, planned to launch to undergraduate Spartans and the MSU community in a traditional campus environment for the 2020-2021 academic year. Significant strategy, resources, and collaboration defined a launch that soon became incongruent to the campuses needs pivoting to remote learning. The My Spartan Story Team shifted strategy to solely virtual methods to grow awareness and education of My Spartan Story and the Spartan Experience Record (a new customizable record displaying learning in non-credit bearing experiences that can be requested alongside the transcript through the Registrar’s Office). Several tactics planned had to be eliminated, and communications and programming methods rethought. Thankfully, time spent investing in website updates, resources and guides, and other methods simply became more invaluable.

Methods

All

Email communications sent to faculty, staff, administrators, and undergraduate students co-created with Provost Communications Team.

Downloadable resources and guides created to assist with workflows and utilization of the My Spartan Story platform.

Faculty/Staff

Strategic outreach to campus community, presenting at unit meetings, and large monthly meetings such as Undergraduate Assistant/Associate Deans and Directors of Undergraduate Affairs (UGAAD).

My Spartan Story Faculty/Staff Workshops held 2-3 times monthly, welcoming organic connection to My Spartan Story.

Students

Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter accounts created; posts organized through Hootsuite. Content regularly shared by campus colleagues and students.

My Spartan Story 101 Workshops offered as well as Registered Student Organization Workshops in partnership with MSU Student Life.

My Spartan Story Week held in collaboration with platform partners Undergraduate Research and Center for Community Engaged Learning.

Contests and giveaways promoting engagement with the My Spartan Story platform held throughout the year.

Regular emails sent to students with a validated position on their Spartan Experience Record.

Virtual attendance at events such as Sparticipation and Spartan Remix.

Results

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Successes

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Challenges

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Future Steps

Within Fall 2020, 87 new positions were submitted for review and inclusion in My Spartan Story, an 89% increase from Fall 2019 (46 positions).

9% of positions (8) received were represented by two new colleges and one new division that previously did not have any submissions.

91% of Fall 2020 submissions received from colleges/divisions we had an established relationship through 2019-2020 soft launch.

The potential number of students who could have a position validated to their Spartan Experience Record increased by 137.5% compared to Fall 2019 (1497 to 3556).

Increased engagement on social media platforms, with nearly 700 collective followers.

Figure Descriptions

Position increase chart

3,556: Potential students who can have a validated position on their record by end of 2020-2021 academic year from Fall 2020 submissions

Social media platforms have significantly driven student engagement, specifically tagging students and organizations in posts.

Colleges & Divisions with Opportunities in My Spartan Story as of Fall 2020

Associate Provost for Teaching, Learning and Technology

Associate Provost for Undergraduate Education

Associate Provost for University Outreach & Engagement

College of Agriculture & Natural Resources

College of Arts & Letters

College of Communication Arts & Sciences

College of Education

College of Engineering

College of Natural Science

College of Osteopathic Medicine

College of Social Science

Division of Residential & Hospitality Services

Eli Broad College of Business

Executive Vice President for Administration

Honors College

International Studies & Programs

James Madison College

Libraries

Office of Civil Rights & Title IX Education & Compliance

Provost & Academic Affairs

Vice President for Research & Graduate Studies

Vice President for Student Affairs & Services

Authored by:

Sarah Schultz

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Lessons Learned Launching a University-Wide Initiative in a Remote Environment

In Fall 2020, the My Spartan Story team launched campus-wide My Spa...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Monday, May 3, 2021

Posted on: Educator Stories

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Featured Educator: Kate Sonka

This week, we are featuring, Kate Sonka, Assistant Director of Inclusion & Academic Technology in the College of Arts and Letters. Kate was recognized via iteach.msu.edu's Thank and Educator Initiative! We encourage MSU community members to nominate high impact Spartan educators (via our Thank an Educator form) regularly!

Read more about Kate's perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by Kate's responses!

In one word, what does being an educator mean to you?

Connection

Share with me what this word/quality looks like in your practice?

This looks like connections between educators and students, connections between learners and course content, connections among students, connections among faculty, and so forth. In that way, I continually keep these possibilities for connections and collaborations in my mind as I work to support teaching and learning in the College of Arts & Letters (CAL) and the broader MSU community. Some of this appears through faculty professional development opportunities I help create and facilitate and it also appears through the grad and undergrad courses I teach. And in a broader sense, it very much features in the work I do as Executive Director of Teach Access.

Have your ideas on this changed over time? if so how?

If anything each day I find more and expansive ways to connect people to ideas and to each other. I’m definitely a life-long learner myself, so as I take in and learn new information or new pedagogies I want to share those out.

Tell me more about your educational “setting.” This can include, but not limited to departmental affiliations, community connections, co-instructors, and students.

I’m situated in the CAL Dean’s office and I report to both the Assistant Dean for Academic and Research Technology AND the Associate Dean of Academic Personnel and Administration. Beyond that, I spend a lot of my time working with colleagues in a variety of colleges and units across MSU.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role?

A challenge I experience is one we all face – how do we meet students where they are and ensure we’re creating inclusive learning spaces for everyone in our class.

Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

Making sure we take the time to actually listen to students. I always include surveys to collect anonymous feedback before the semester, mid-way through, and at the end asking about how inclusive (or not) I’ve been as an educator and recommendations on how to help them meet their learning goals. And wherever I can, I try to incorporate that feedback while I still have students in the class, and/or use that feedback to improve the course the next time I teach it.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

Certainly the student surveys I mentioned above help me understand if I’m being successful, but also any sort of additional feedback I can get from students or colleagues also helps.

What topics or ideas about teaching and learning would you like to see discussed on the iteach.msu.edu platform? Why do you think this conversation is needed at msu?

I would love to see more conversations about how people are creating accessible learning environments and how considering students with disabilities improves their overall teaching practice. We’ve made some progress in this area since I’ve been at MSU, but the more we could share with each other, the more I think other educators would be energized to try in their own classes.

What are you looking forward to (or excited to be a part of) next semester?

I’ve been doing more work with the CAL Inclusive Pedagogy Initiative, and we were just considering a two-part workshop series on topics of inclusion. Excited to see how this work expands in our college and beyond!

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature! Follow the MSU Hub Twitter account to see other great content from the #iteachmsu Commons as well as educators featured every week during #ThankfulThursdays.

Read more about Kate's perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by Kate's responses!

In one word, what does being an educator mean to you?

Connection

Share with me what this word/quality looks like in your practice?

This looks like connections between educators and students, connections between learners and course content, connections among students, connections among faculty, and so forth. In that way, I continually keep these possibilities for connections and collaborations in my mind as I work to support teaching and learning in the College of Arts & Letters (CAL) and the broader MSU community. Some of this appears through faculty professional development opportunities I help create and facilitate and it also appears through the grad and undergrad courses I teach. And in a broader sense, it very much features in the work I do as Executive Director of Teach Access.

Have your ideas on this changed over time? if so how?

If anything each day I find more and expansive ways to connect people to ideas and to each other. I’m definitely a life-long learner myself, so as I take in and learn new information or new pedagogies I want to share those out.

Tell me more about your educational “setting.” This can include, but not limited to departmental affiliations, community connections, co-instructors, and students.

I’m situated in the CAL Dean’s office and I report to both the Assistant Dean for Academic and Research Technology AND the Associate Dean of Academic Personnel and Administration. Beyond that, I spend a lot of my time working with colleagues in a variety of colleges and units across MSU.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role?

A challenge I experience is one we all face – how do we meet students where they are and ensure we’re creating inclusive learning spaces for everyone in our class.

Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

Making sure we take the time to actually listen to students. I always include surveys to collect anonymous feedback before the semester, mid-way through, and at the end asking about how inclusive (or not) I’ve been as an educator and recommendations on how to help them meet their learning goals. And wherever I can, I try to incorporate that feedback while I still have students in the class, and/or use that feedback to improve the course the next time I teach it.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

Certainly the student surveys I mentioned above help me understand if I’m being successful, but also any sort of additional feedback I can get from students or colleagues also helps.

What topics or ideas about teaching and learning would you like to see discussed on the iteach.msu.edu platform? Why do you think this conversation is needed at msu?

I would love to see more conversations about how people are creating accessible learning environments and how considering students with disabilities improves their overall teaching practice. We’ve made some progress in this area since I’ve been at MSU, but the more we could share with each other, the more I think other educators would be energized to try in their own classes.

What are you looking forward to (or excited to be a part of) next semester?

I’ve been doing more work with the CAL Inclusive Pedagogy Initiative, and we were just considering a two-part workshop series on topics of inclusion. Excited to see how this work expands in our college and beyond!

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature! Follow the MSU Hub Twitter account to see other great content from the #iteachmsu Commons as well as educators featured every week during #ThankfulThursdays.

Authored by:

Kristen Surla

Posted on: Educator Stories

Featured Educator: Kate Sonka

This week, we are featuring, Kate Sonka, Assistant Director of Incl...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Feb 15, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

How Video Length Affects Student Learning – The Shorter, The Better!

In-Person Lectures vs. Online Instruction

Actively engaging students in the learning process is important for both in-person lectures and for online instruction. The ways in which students engage with the instructor, their peers, and the course materials will vary based on the setting. In-person courses are often confined by the fact that instruction needs to be squeezed into a specific time period, which can result in there being a limited amount of time for students to perform group work or to actively think about the concepts they are learning. Alternatively, with online instruction, there is often more freedom (especially for an asynchronous course) on how you can present materials and structure the learning environment.

Currently, many instructors are faced with the challenge of adapting their in-person courses into an online format. How course materials are adapted into an online format are going to differ from course to course – however, a common practice shared across courses is to create lecture recordings or videos for students to watch. The format and length of these videos play an important role in the learning experience students have within a course. The ways in which students engage with a longer video recording is going to be much different than how students engage with multiple shorter videos. Below are some of the important reasons why shorter videos can enhance student learning when compared to longer videos.

More Opportunities for Students to Actively Engage with the Material

Decades of research on how people learn has shown that active learning (in comparison to more passive approaches, such as direct instruction or a traditional lecture) enhances student performance (Freeman et. al., 2014). While “active learning” can often be a nebulous phrase that has different meanings, active learning can be broadly thought of as any activity in which a learner is metacognitively thinking about and applying knowledge to accomplish some goal or task. Providing multiple opportunities for students to engage in these types of activities can help foster a more meaningful and inclusive learning environment for students. This is especially important for online instruction as students may feel isolated or have a difficult time navigating their learning within a virtual environment.

One of the biggest benefits of creating a series of shorter videos compared to creating one long video is that active learning techniques and activities can be more easily utilized and interspersed throughout a lesson. For example, if you were to record a video of a traditional lecture period, your video would be nearly an hour in length, and it would likely cover multiple important topics within that time period. Creating opportunities to actively engage students throughout an hour-long video is difficult and can result in students feeling overwhelmed.

Conversely, one of the affordances of online instruction is that lectures can be broken down into a series of smaller video lessons and activities. By having shorter videos with corresponding activities, students are going to spend more time actively thinking about and applying their understanding of concepts throughout a lesson. This in turn can promote metacognition by getting students to think about their thinking after each short video rather than at the end of a long video that covers multiple topics.

Additionally, concepts often build upon one another, and it is critical that students develop a solid foundation of prior knowledge before moving onto more complex topics. When you create multiple short videos and activities, it can be easier to get a snapshot of how students conceptualize different topics as they are learning it. This information can help both you as an instructor and your students become better aware of when they are having difficulties so that issues can be addressed before moving onto more complex topics. With longer videos, students may be confused on concepts discussed at the beginning of the video, which can then make it difficult for them to understand subsequent concepts.

Overall, chunking a longer video into multiple shorter videos is a simple technique you can use to create more meaningful learning opportunities in a virtual setting. Short videos, coupled with corresponding activities, is a powerful pedagogical approach to enhance student learning.

Reducing Cognitive Load

Another major benefit of having multiple shorter videos instead of one longer video is that it can reduce the cognitive load that students experience when engaging with the content. Learning is a process that requires the brain to adapt, develop, and ultimately form new neural connections in response to stimuli (National Academies of Sciences, 2018). If a video is long and packed with content, developing a meaningful understanding of concepts can be quite difficult. Even if the content is explained in detail (which many people think of as “good instruction”), students simply do not have enough time to process and critically think about the content they are learning. When taking in various stimuli and trying to comprehend multiple concepts, this can result in students feeling anxious and overwhelmed. Having time to self-reflect is one of the most important factors to promoting a deeper, more meaningful learning experience. Unfortunately, long video lectures provide few opportunities (even when done well!) for students to engage in these types of thinking and doing.

Additionally, an unintended drawback of long videos is that the listener can be lulled into a false sense of understanding. For example, have you ever watched a live lecture or an educational video where you followed along and felt like you understood the material, but then after when you went to apply this knowledge, you realized that you forgot or did not understand the content as well as you thought? Everyone has experienced this phenomenon in some form or another. As students watch long video lectures, especially lectures that have clear explanations of the content, they may get a false sense of how well they understand the material. This can result in students overestimating their ability and grasp of foundational ideas, which in turn, can make future learning more difficult as subsequent knowledge will be built upon a faulty base.

Long lecture videos are also more prone to having extraneous information or tangential discussions throughout. This additional information may cause students to shift their cognitive resources away from the core course content, resulting in a less meaningful learning experience (Mayer & Moreno, 2003). Breaking a long video into multiple shorter videos can reduce the cognitive load students may experience and it can create more opportunities for them to self-reflect on what they are learning.

More Engaging for Students

Another important factor to think about is how video length affects student engagement. A study by Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014) looked at how different forms of video production affected student engagement when watching videos. Two of their main findings were that (1) shorter videos improve student engagement, and that (2) recordings of traditional lectures are less engaging compared to digital tablet drawing or PowerPoint slide presentations. These findings show how it is not only important to record shorter videos, but that simply recording a traditional lecture and splicing it into smaller videos will not result in the most engaging experience for students.

When distilling a traditional lecture into a series of shorter videos, it is important to think about the pedagogical techniques you would normally use in the classroom and how these approaches might translate to an online setting. Identifying how these approaches might be adapted into a video recording can help create a more engaging experience for students in your course.

Overall, the length of lecture videos and the ways in which they are structured directly impacts how students learn in a virtual setting. Recording short, interactive videos, as opposed to long lecture videos, is a powerful technique you can use to enhance student learning and engagement.

References

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50).

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 43-52.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press.

Actively engaging students in the learning process is important for both in-person lectures and for online instruction. The ways in which students engage with the instructor, their peers, and the course materials will vary based on the setting. In-person courses are often confined by the fact that instruction needs to be squeezed into a specific time period, which can result in there being a limited amount of time for students to perform group work or to actively think about the concepts they are learning. Alternatively, with online instruction, there is often more freedom (especially for an asynchronous course) on how you can present materials and structure the learning environment.

Currently, many instructors are faced with the challenge of adapting their in-person courses into an online format. How course materials are adapted into an online format are going to differ from course to course – however, a common practice shared across courses is to create lecture recordings or videos for students to watch. The format and length of these videos play an important role in the learning experience students have within a course. The ways in which students engage with a longer video recording is going to be much different than how students engage with multiple shorter videos. Below are some of the important reasons why shorter videos can enhance student learning when compared to longer videos.

More Opportunities for Students to Actively Engage with the Material

Decades of research on how people learn has shown that active learning (in comparison to more passive approaches, such as direct instruction or a traditional lecture) enhances student performance (Freeman et. al., 2014). While “active learning” can often be a nebulous phrase that has different meanings, active learning can be broadly thought of as any activity in which a learner is metacognitively thinking about and applying knowledge to accomplish some goal or task. Providing multiple opportunities for students to engage in these types of activities can help foster a more meaningful and inclusive learning environment for students. This is especially important for online instruction as students may feel isolated or have a difficult time navigating their learning within a virtual environment.

One of the biggest benefits of creating a series of shorter videos compared to creating one long video is that active learning techniques and activities can be more easily utilized and interspersed throughout a lesson. For example, if you were to record a video of a traditional lecture period, your video would be nearly an hour in length, and it would likely cover multiple important topics within that time period. Creating opportunities to actively engage students throughout an hour-long video is difficult and can result in students feeling overwhelmed.

Conversely, one of the affordances of online instruction is that lectures can be broken down into a series of smaller video lessons and activities. By having shorter videos with corresponding activities, students are going to spend more time actively thinking about and applying their understanding of concepts throughout a lesson. This in turn can promote metacognition by getting students to think about their thinking after each short video rather than at the end of a long video that covers multiple topics.

Additionally, concepts often build upon one another, and it is critical that students develop a solid foundation of prior knowledge before moving onto more complex topics. When you create multiple short videos and activities, it can be easier to get a snapshot of how students conceptualize different topics as they are learning it. This information can help both you as an instructor and your students become better aware of when they are having difficulties so that issues can be addressed before moving onto more complex topics. With longer videos, students may be confused on concepts discussed at the beginning of the video, which can then make it difficult for them to understand subsequent concepts.

Overall, chunking a longer video into multiple shorter videos is a simple technique you can use to create more meaningful learning opportunities in a virtual setting. Short videos, coupled with corresponding activities, is a powerful pedagogical approach to enhance student learning.

Reducing Cognitive Load

Another major benefit of having multiple shorter videos instead of one longer video is that it can reduce the cognitive load that students experience when engaging with the content. Learning is a process that requires the brain to adapt, develop, and ultimately form new neural connections in response to stimuli (National Academies of Sciences, 2018). If a video is long and packed with content, developing a meaningful understanding of concepts can be quite difficult. Even if the content is explained in detail (which many people think of as “good instruction”), students simply do not have enough time to process and critically think about the content they are learning. When taking in various stimuli and trying to comprehend multiple concepts, this can result in students feeling anxious and overwhelmed. Having time to self-reflect is one of the most important factors to promoting a deeper, more meaningful learning experience. Unfortunately, long video lectures provide few opportunities (even when done well!) for students to engage in these types of thinking and doing.

Additionally, an unintended drawback of long videos is that the listener can be lulled into a false sense of understanding. For example, have you ever watched a live lecture or an educational video where you followed along and felt like you understood the material, but then after when you went to apply this knowledge, you realized that you forgot or did not understand the content as well as you thought? Everyone has experienced this phenomenon in some form or another. As students watch long video lectures, especially lectures that have clear explanations of the content, they may get a false sense of how well they understand the material. This can result in students overestimating their ability and grasp of foundational ideas, which in turn, can make future learning more difficult as subsequent knowledge will be built upon a faulty base.

Long lecture videos are also more prone to having extraneous information or tangential discussions throughout. This additional information may cause students to shift their cognitive resources away from the core course content, resulting in a less meaningful learning experience (Mayer & Moreno, 2003). Breaking a long video into multiple shorter videos can reduce the cognitive load students may experience and it can create more opportunities for them to self-reflect on what they are learning.

More Engaging for Students

Another important factor to think about is how video length affects student engagement. A study by Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014) looked at how different forms of video production affected student engagement when watching videos. Two of their main findings were that (1) shorter videos improve student engagement, and that (2) recordings of traditional lectures are less engaging compared to digital tablet drawing or PowerPoint slide presentations. These findings show how it is not only important to record shorter videos, but that simply recording a traditional lecture and splicing it into smaller videos will not result in the most engaging experience for students.

When distilling a traditional lecture into a series of shorter videos, it is important to think about the pedagogical techniques you would normally use in the classroom and how these approaches might translate to an online setting. Identifying how these approaches might be adapted into a video recording can help create a more engaging experience for students in your course.

Overall, the length of lecture videos and the ways in which they are structured directly impacts how students learn in a virtual setting. Recording short, interactive videos, as opposed to long lecture videos, is a powerful technique you can use to enhance student learning and engagement.

References

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50).

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 43-52.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press.

Authored by:

Christopher J. Minter

Posted on: #iteachmsu

How Video Length Affects Student Learning – The Shorter, The Better!

In-Person Lectures vs. Online Instruction

Actively engaging student...

Actively engaging student...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, Sep 2, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

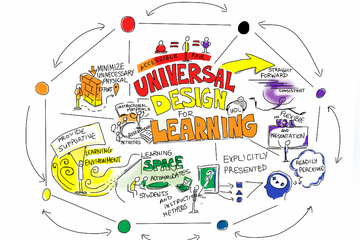

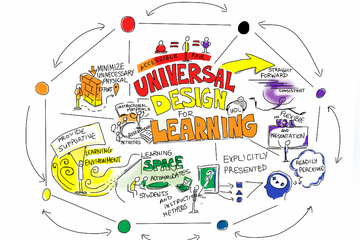

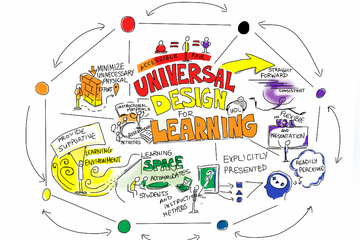

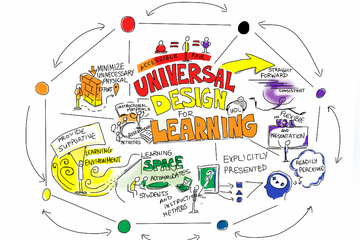

Universal Design for Learning

What is Universal Design for Learning?

According to the CAST website, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is “a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn.” Although UDL is not exclusive to digital accessibility, this framework prioritizes inclusivity and thus inherently lends itself to the creation of courses that are accessible to all students.

UDL is built on an understanding of the term learning as the interaction and layering of:

Recognition, or the “what”

Skills and Strategies, or the “how”

Caring and Prioritizing, or the “why”

The ultimate goal of UDL is to design a course that is accessible to everyone from its very inception and is open to flexibility. UDL can help instructors create accessible goals, methods, materials, and assessments.

UDL proposes the following three principles to upend barriers to learning:

Representation - present material in a variety of ways

Action and Expression - allow students to share what they know in their own

Engagement - provide students with choices

Explore this topic further in CAST’s “UDL at a Glance”:

UDL GuidelinesLearn more about the Guildlines for UDL via the accessible and interactive table on the CAST website.

Instructional Technology and Development’s Incorporating Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into Your Course Design

Further Reading

Michigan Tech’s guide for UDL

Weaver Library’s Research Guide Universal Design for Learning (UDL) & Accessibility for Faculty

Introduction to Universal Learning Design (UDL) by Shannon Kelly

Sources

About universal design for learning. CAST. (2024, March 28). https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

This article is part of the Digital Accessibility Toolkit.

According to the CAST website, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is “a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn.” Although UDL is not exclusive to digital accessibility, this framework prioritizes inclusivity and thus inherently lends itself to the creation of courses that are accessible to all students.

UDL is built on an understanding of the term learning as the interaction and layering of:

Recognition, or the “what”

Skills and Strategies, or the “how”

Caring and Prioritizing, or the “why”

The ultimate goal of UDL is to design a course that is accessible to everyone from its very inception and is open to flexibility. UDL can help instructors create accessible goals, methods, materials, and assessments.

UDL proposes the following three principles to upend barriers to learning:

Representation - present material in a variety of ways

Action and Expression - allow students to share what they know in their own

Engagement - provide students with choices

Explore this topic further in CAST’s “UDL at a Glance”:

UDL GuidelinesLearn more about the Guildlines for UDL via the accessible and interactive table on the CAST website.

Instructional Technology and Development’s Incorporating Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into Your Course Design

Further Reading

Michigan Tech’s guide for UDL

Weaver Library’s Research Guide Universal Design for Learning (UDL) & Accessibility for Faculty

Introduction to Universal Learning Design (UDL) by Shannon Kelly

Sources

About universal design for learning. CAST. (2024, March 28). https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

This article is part of the Digital Accessibility Toolkit.

Posted by:

Katherine Knowles

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Universal Design for Learning

What is Universal Design for Learning?

According to the CAST websit...

According to the CAST websit...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, Apr 24, 2024

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment in a Synchronous, Flipped Course

The move to online learning in response to COVID-19 brought both challenges and opportunities. An off-campus, flipped section of ANTR 350 has been offered in Grand Rapids during the summer since 2017. When Michigan State University moved to online learning for summer 2020, the class was adapted to a Zoom-based, synchronous model. Students were required to complete online learning modules as preparation for each class. During class, students worked in small groups to complete application activities in Zoom breakout rooms.

Groups were assigned and reconfigured for each unit. The instructor provided recommendations for working effectively in a group and students received feedback after the first and third units regarding their teamwork skills and class performance. Unit exams were two-stage examinations, consisting of an individual exam followed immediately by a group exam. These examinations were timed and proctored over Zoom by faculty and staff.

Students and faculty faced many technological, health, and personal challenges during the semester. However, students demonstrated tremendous resilience and flexibility. Overall, the course was a very positive experience; student performance and SIRS ratings were higher than during previous iterations of the course. The instructor observed improved group work skills, which was mirrored by student feedback. Overall, we were able to retain the flipped approach and emphasis on group work by using Zoom breakout rooms to simulate a collaborative learning environment comparable to that of the in-person experience.

To access a PDF of the "Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment in a Synchronous, Flipped Course" poster, click here.

Description of the Poster

Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment in a Synchronous, Flipped Course

Ryan Maureen Tubbs, Department of Radiology, Division of Human Anatomy, College of Human Medicine

Alexis Amos, Michigan State University, Psychology Major, Senior

ANTR 350 Goes Virtual

ANTR 350, Human Gross Anatomy for Pre-Health Professionalsis an undergraduate course traditionally offered as large, in-person lecture sections on main campus and as a flipped, in-person section in Grand Rapids during summer semesters.

When Michigan State University moved to online learning for summer 2020, the class was adapted to a Zoom-based, synchronous model. Students were required to complete online learning modules as preparation for each class. During class, students worked in small groups to complete application activities in Zoom breakout rooms. The move to online learning in response to COVID-19 brought both challenges and opportunities in terms of creating a collaborative learning environment.

An online preparatory assignment was due at start of each class

Readings interspersed with videos, interactive models, and questions

Guided by specific learning objectives

Variable number of questions but each assignment worth 2pts (total 11.2% of grade)

Image: screenshot of a portion of a Top Hat Assignment titled "Preparatory Reading June 9". Some of the learning objectives and headings are shown.

During class, students primarily collaborated in Zoom breakout rooms to review and apply the content covered in the preparatory assignment. The instructor moved between rooms to check on group progress and answer questions. Most in-class activities utilized Google docs or Top Hat, so the instructor could also observe group progress in real time. For most activities, keys were available during class so that groups did not end up stuck on any questions.

10:00-10:03 Application prompt while people logged in, answers entered in zoom chat

10:04-10:15 Synchronous, Top Hat-based Readiness Quiz, 5 questions

10:15-11:45 Groupwork and mini-lectures*

11:45-11:50 Post-class survey soliciting feedback on activities & overall session

Image: screenshot of example application exercise using Google Docs. A CT is shown on the right side of the image and a series of questions is shown on the left. Students answers to the questions are shown in blue.

Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment

The importance of developing teamwork skills was emphasized in the syllabus and during the course overview presentation. Students were given descriptions of five different group roles (leader, learner, time-keeper, recorder, and summarizer) and asked to try moving between the roles. Students were asked to read and agree to expectations for student interactions, including keeping camera on when possible, actively engaging with the group, agreeing not to take screenshots or record the session, and guidelines about private chats. The instructor acknowledged the awkwardness of working with strangers over zoom and asked all students to be generous of spirit with each other.

A brief ice-breaker activity was assigned at the start of each unit to give students an opportunity to develop their collaborative learning relationships. After each unit, students were asked to give honest feedback to the instructor about each of their groupmates’ collaborative learning skills. Students received feedback summaries and recommendations about how to improve their collaborative skills at the end of units 1 and 3. Groups were also asked to set ground rules and group goals at the start of units 2 and 3.

Image: screenshot of June 9 Top Hat In-Class Page. Activity 1 is an ice breaker for new groups. Activity 2 is an axial muscles google doc groupwork exercise. Activity 3 is the review of that google doc as a whole class and Activity 4 is setting Unit 2 goals.

The importance of collaborative learning was emphasized by the inclusion of collaborative testing. Unit exams consisted of an individual exam followed immediately by the same exam taken in their groups. The group exam contributed 16.67% to each unit exam score.

Student feedback was collected in SIRS, post-class, and post-course surveys

Student Feedback

Image: bar chart showing responses to "How many of your classmates that you did not know previously did you communicate with outside of class during the semester?"

Fall 2019 (in-person section): Average of 1.3125

Spring 2020 (Fall 2019 (in-person section until COVID moved asynchronous): Average of 1.2181

Summer 2020 (sychronous zoom) 1.5625

Fall 2020 (asynchronous online) 0.8082

Image: bar chart showing response to "Overall, did you have someone you could reach out to if you struggled with content during this course?"

Fall 2019 (in-person):

Yes for all units 79.2%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 0%

Yes, for 1 or two units 12.5%

No, I never really did 8.3%

Spring 2020 (mostly in-person)

Yes for all units 67.3%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 5.4%

Yes, for 1 or two units 16.3%

No, I never really did 10.9%

Summer 2020 (synchronous, virtual)

Yes for all units 81.3%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 0%

Yes, for 1 or two units 6.2%

No, I never really did 12.5%

Fall 2020 (asychronous, virtual)

Yes for all units 60.8%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 5.4%

Yes, for 1 or two units 14.9%

No, I never really did 18.9%

Spring 2021 (asychronous, current course)

Yes for all units 54.7%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 4.7%

Yes, for 1 or two units 16.1%

No, I never really did 24.5%

Image: 100% Stacked Column Chart showing student responses to "How comfortable did you feel reaching out to a course instructor if you struggled with content?"

Fall 2019

Extremely Comfortable 54%

Somewhat comfortable 29%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 8%

Somewhat uncomfortable 4%

Extremely uncomfortable 4%

Spring 2020

Extremely Comfortable 36%

Somewhat comfortable 29%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 20%

Somewhat uncomfortable 15%

Extremely uncomfortable 0%

Summer 2020

Extremely Comfortable 87%

Somewhat comfortable 0%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 13%

Somewhat uncomfortable 0%

Extremely uncomfortable 0%

Fall 2020

Extremely Comfortable 39%

Somewhat comfortable 32%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 18%

Somewhat uncomfortable 8%

Extremely uncomfortable 3%

Spring 2021

Extremely Comfortable 35%

Somewhat comfortable 30%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 30%

Somewhat uncomfortable 4%

Extremely uncomfortable 2%

Image: Pie Chart Titled "Overall, how supported did you feel during this course compared to other courses you have taken?” (Summer 2020)

Far above average is shown as 81%, Somewhat above average is shown as 13%, Average is shown as 6%. Somewhat below average and far below average are listed in the legend but not represented in the chart as they are 0%

Conclusions

Summer 2020 was a hard semester for everyone. We all faced many technological, health, and personal challenges during the semester. Despite these challenges, students demonstrated tremendous resilience and we were able to create a collaborative learning environment using Zoom breakout rooms. Overall, the course was a very positive experience; student performance and SIRS ratings were higher than during previous Summer iterations of the course. In addition, students felt more connected compared to the asynchronous Fall sections.

Image: Table “Student Performance”

Number of students enrolled in course:

Summer 2019: 22

Spring 2020: 338

Summer 2020: 52

Number of students withdrawn from course:

Summer 2019: 0

Spring 2020: 1

Summer 2020: 0

Mean percent score overall:

Summer 2019: 82.85%

Spring 2020: 90.19%

Summer 2020: 89.03%

Number of students with passing scores (2.0 or higher):

Summer 2019: 20

Spring 2020: 332

Summer 2020: 50

Number of students with failing scores (1.5 of lower):

Summer 2019: 2

Spring 2020: 4

Summer 2020: 2

Percentage of students with failing scores:

Summer 2019: 9%

Spring 2020: 1%

Summer 2020: 3.8%

Image: Results of MSU Student Instructional Rating System (SIRS)

Summer 2019 SIRS

Course Organization

Superior 33.3%

Above Average 55.5%

Average 11.1%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Adequacy of the outlined direction of the course

Superior 33.3%

Above Average 55.5%

Average 11.1%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Your general enjoyment of the course

Superior 33.3%

Above Average 44.4%

Average 22.2%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Summer 2020 SIRS

Course Organization

Superior 70.9%

Above Average 19.3%

Average 6.45%

Below Average 3.22%

Inferior 0%

Adequacy of the outlined direction of the course

Superior 77.4%

Above Average 16.1%

Average 6.45%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Your general enjoyment of the course

Superior 54.8%

Above Average 38.7%

Average 6.45%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

References

Gaillard, Frank. “Acute Maxillary Sinusitis: Radiology Case.” Radiopaedia Blog RSS, radiopaedia.org/cases/acute-maxillary-sinusitis?lang=us.

ANTR 350 Top Hat Course. www.tophat.com

Acknowledgments

A giant thank you to the ANTR 350 Summer Class of 2020!

Groups were assigned and reconfigured for each unit. The instructor provided recommendations for working effectively in a group and students received feedback after the first and third units regarding their teamwork skills and class performance. Unit exams were two-stage examinations, consisting of an individual exam followed immediately by a group exam. These examinations were timed and proctored over Zoom by faculty and staff.

Students and faculty faced many technological, health, and personal challenges during the semester. However, students demonstrated tremendous resilience and flexibility. Overall, the course was a very positive experience; student performance and SIRS ratings were higher than during previous iterations of the course. The instructor observed improved group work skills, which was mirrored by student feedback. Overall, we were able to retain the flipped approach and emphasis on group work by using Zoom breakout rooms to simulate a collaborative learning environment comparable to that of the in-person experience.

To access a PDF of the "Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment in a Synchronous, Flipped Course" poster, click here.

Description of the Poster

Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment in a Synchronous, Flipped Course

Ryan Maureen Tubbs, Department of Radiology, Division of Human Anatomy, College of Human Medicine

Alexis Amos, Michigan State University, Psychology Major, Senior

ANTR 350 Goes Virtual

ANTR 350, Human Gross Anatomy for Pre-Health Professionalsis an undergraduate course traditionally offered as large, in-person lecture sections on main campus and as a flipped, in-person section in Grand Rapids during summer semesters.

When Michigan State University moved to online learning for summer 2020, the class was adapted to a Zoom-based, synchronous model. Students were required to complete online learning modules as preparation for each class. During class, students worked in small groups to complete application activities in Zoom breakout rooms. The move to online learning in response to COVID-19 brought both challenges and opportunities in terms of creating a collaborative learning environment.

An online preparatory assignment was due at start of each class

Readings interspersed with videos, interactive models, and questions

Guided by specific learning objectives

Variable number of questions but each assignment worth 2pts (total 11.2% of grade)

Image: screenshot of a portion of a Top Hat Assignment titled "Preparatory Reading June 9". Some of the learning objectives and headings are shown.

During class, students primarily collaborated in Zoom breakout rooms to review and apply the content covered in the preparatory assignment. The instructor moved between rooms to check on group progress and answer questions. Most in-class activities utilized Google docs or Top Hat, so the instructor could also observe group progress in real time. For most activities, keys were available during class so that groups did not end up stuck on any questions.

10:00-10:03 Application prompt while people logged in, answers entered in zoom chat

10:04-10:15 Synchronous, Top Hat-based Readiness Quiz, 5 questions

10:15-11:45 Groupwork and mini-lectures*

11:45-11:50 Post-class survey soliciting feedback on activities & overall session

Image: screenshot of example application exercise using Google Docs. A CT is shown on the right side of the image and a series of questions is shown on the left. Students answers to the questions are shown in blue.

Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment

The importance of developing teamwork skills was emphasized in the syllabus and during the course overview presentation. Students were given descriptions of five different group roles (leader, learner, time-keeper, recorder, and summarizer) and asked to try moving between the roles. Students were asked to read and agree to expectations for student interactions, including keeping camera on when possible, actively engaging with the group, agreeing not to take screenshots or record the session, and guidelines about private chats. The instructor acknowledged the awkwardness of working with strangers over zoom and asked all students to be generous of spirit with each other.

A brief ice-breaker activity was assigned at the start of each unit to give students an opportunity to develop their collaborative learning relationships. After each unit, students were asked to give honest feedback to the instructor about each of their groupmates’ collaborative learning skills. Students received feedback summaries and recommendations about how to improve their collaborative skills at the end of units 1 and 3. Groups were also asked to set ground rules and group goals at the start of units 2 and 3.

Image: screenshot of June 9 Top Hat In-Class Page. Activity 1 is an ice breaker for new groups. Activity 2 is an axial muscles google doc groupwork exercise. Activity 3 is the review of that google doc as a whole class and Activity 4 is setting Unit 2 goals.

The importance of collaborative learning was emphasized by the inclusion of collaborative testing. Unit exams consisted of an individual exam followed immediately by the same exam taken in their groups. The group exam contributed 16.67% to each unit exam score.

Student feedback was collected in SIRS, post-class, and post-course surveys

Student Feedback

Image: bar chart showing responses to "How many of your classmates that you did not know previously did you communicate with outside of class during the semester?"

Fall 2019 (in-person section): Average of 1.3125

Spring 2020 (Fall 2019 (in-person section until COVID moved asynchronous): Average of 1.2181

Summer 2020 (sychronous zoom) 1.5625

Fall 2020 (asynchronous online) 0.8082

Image: bar chart showing response to "Overall, did you have someone you could reach out to if you struggled with content during this course?"

Fall 2019 (in-person):

Yes for all units 79.2%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 0%

Yes, for 1 or two units 12.5%

No, I never really did 8.3%

Spring 2020 (mostly in-person)

Yes for all units 67.3%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 5.4%

Yes, for 1 or two units 16.3%

No, I never really did 10.9%

Summer 2020 (synchronous, virtual)

Yes for all units 81.3%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 0%

Yes, for 1 or two units 6.2%

No, I never really did 12.5%

Fall 2020 (asychronous, virtual)

Yes for all units 60.8%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 5.4%

Yes, for 1 or two units 14.9%

No, I never really did 18.9%

Spring 2021 (asychronous, current course)

Yes for all units 54.7%

Yes, for 3 or 4 units 4.7%

Yes, for 1 or two units 16.1%

No, I never really did 24.5%

Image: 100% Stacked Column Chart showing student responses to "How comfortable did you feel reaching out to a course instructor if you struggled with content?"

Fall 2019

Extremely Comfortable 54%

Somewhat comfortable 29%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 8%

Somewhat uncomfortable 4%

Extremely uncomfortable 4%

Spring 2020

Extremely Comfortable 36%

Somewhat comfortable 29%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 20%

Somewhat uncomfortable 15%

Extremely uncomfortable 0%

Summer 2020

Extremely Comfortable 87%

Somewhat comfortable 0%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 13%

Somewhat uncomfortable 0%

Extremely uncomfortable 0%

Fall 2020

Extremely Comfortable 39%

Somewhat comfortable 32%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 18%

Somewhat uncomfortable 8%

Extremely uncomfortable 3%

Spring 2021

Extremely Comfortable 35%

Somewhat comfortable 30%

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable 30%

Somewhat uncomfortable 4%

Extremely uncomfortable 2%

Image: Pie Chart Titled "Overall, how supported did you feel during this course compared to other courses you have taken?” (Summer 2020)

Far above average is shown as 81%, Somewhat above average is shown as 13%, Average is shown as 6%. Somewhat below average and far below average are listed in the legend but not represented in the chart as they are 0%

Conclusions

Summer 2020 was a hard semester for everyone. We all faced many technological, health, and personal challenges during the semester. Despite these challenges, students demonstrated tremendous resilience and we were able to create a collaborative learning environment using Zoom breakout rooms. Overall, the course was a very positive experience; student performance and SIRS ratings were higher than during previous Summer iterations of the course. In addition, students felt more connected compared to the asynchronous Fall sections.

Image: Table “Student Performance”

Number of students enrolled in course:

Summer 2019: 22

Spring 2020: 338

Summer 2020: 52

Number of students withdrawn from course:

Summer 2019: 0

Spring 2020: 1

Summer 2020: 0

Mean percent score overall:

Summer 2019: 82.85%

Spring 2020: 90.19%

Summer 2020: 89.03%

Number of students with passing scores (2.0 or higher):

Summer 2019: 20

Spring 2020: 332

Summer 2020: 50

Number of students with failing scores (1.5 of lower):

Summer 2019: 2

Spring 2020: 4

Summer 2020: 2

Percentage of students with failing scores:

Summer 2019: 9%

Spring 2020: 1%

Summer 2020: 3.8%

Image: Results of MSU Student Instructional Rating System (SIRS)

Summer 2019 SIRS

Course Organization

Superior 33.3%

Above Average 55.5%

Average 11.1%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Adequacy of the outlined direction of the course

Superior 33.3%

Above Average 55.5%

Average 11.1%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Your general enjoyment of the course

Superior 33.3%

Above Average 44.4%

Average 22.2%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Summer 2020 SIRS

Course Organization

Superior 70.9%

Above Average 19.3%

Average 6.45%

Below Average 3.22%

Inferior 0%

Adequacy of the outlined direction of the course

Superior 77.4%

Above Average 16.1%

Average 6.45%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

Your general enjoyment of the course

Superior 54.8%

Above Average 38.7%

Average 6.45%

Below Average 0%

Inferior 0%

References

Gaillard, Frank. “Acute Maxillary Sinusitis: Radiology Case.” Radiopaedia Blog RSS, radiopaedia.org/cases/acute-maxillary-sinusitis?lang=us.

ANTR 350 Top Hat Course. www.tophat.com

Acknowledgments

A giant thank you to the ANTR 350 Summer Class of 2020!

Authored by:

Ryan Tubbs, Alexis Amos

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Creating a Collaborative Learning Environment in a Synchronous, Flipped Course

The move to online learning in response to COVID-19 brought both ch...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Apr 26, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Corey Marsh Ecological Research Center: Create a unique place-based teaching and learning experience

Work with us to create a unique teaching and learning experience at CMERC.

You are invited to incorporate nature into courses and create learner‐centered experiences at CMERC (pronounced ‘see‐merk’), the Corey Marsh Ecological Research Center. CMERC is a 350‐acre ecological research center located 20 minutes from MSU campus in Bath Township, Michigan. It is a place for making scientific discoveries and integrating the arts and sciences in a collaborative, interdisciplinary, and inclusive space. CMERC welcomes educators, researchers, and citizens across MSU to explore, co‐create, facilitate and grow experiential courses for students.

CMERC seeks faculty and academic staff collaborators to develop learning experiences that will bring together educators, students, and community members to explore and learn from this vibrant ecological field site. MSU faculty and staff from across campus interested in this funded opportunity to join a SoTL Fellowship in land-based learning can connect with Jeno Rivera, Center Educational Program Development Leader at jeno@msu.edu.What is Corey Marsh (CMERC)?

CMERC is more than a physical place. It is a space that offers meaningful place-based experiences.CMERC was once MSU’s Muck Soils Research Center and operated from 1941 – 2012. In 2018, Fisheries and Wildlife associate professor Jen Owen, with the support of MSU AgBioResearch, led the reimagined CMERC into a place for integrating ecosystem science research with student learning and community engagement. In addition to training MSU undergraduate students in field‐based research and science communication, the center aims to promote better land stewardship practices and the relevance of science to society. While still early in its development as an AgBioResearch site, CMERC has been engaging in a people-centered approach to the planning, design and management of the space. CMERC foresees a collaborative process transforming the space to a place that engages a diverse community – internal and external to the university in scientific discovery.Location of Corey Marsh Ecological Research Center in Bath TownshipHow can I contribute?

Given the unique opportunity CMERC provides to enhance student learning, we want to make sure that it serves a diverse student community that spans disciplines and units. We want educators in our SoTL Fellowship in land-based learning to reflect that diversity and help develop curriculum that will foster collaboration among students and serve to integrate arts and humanities with sciences. Consider these examples of possible learning experiences at CMERC:

Edible and Medicinal Plants – for humans and wildlife. What is good for humans vs. wildlife? What grows in muck soils? How can ecological restoration efforts incorporate edible plants? What is missing that was likely at CMERC in the past?

Trails – People – Nature – Wildlife: How does trail design enhance natural experiences and maintain integrity of the ecosystem? What informs the development of a trail?

Land Grant or Land Grab?: Who was here before us? How did this land become a part of the land-grant system? How can this land honor those who used it in the past, present, and the future?

Agriculture and Natural Resources – how can we document and understand how historic land-use affects ecosystem integrity now and in the future?

CMERC actively seeks MSU faculty and staff interested in designing and facilitating an interdisciplinary, learner-centered, sense-making experience built on the resources of CMERC. This curricular/co-curricular programming will be titled Lessons from Nature: Stories from CMERC. We envision that the learning inquiries would be co-created by faculty and students together. More specifically, the lessons will be shaped as a studio experience that is akin to Liberty Hyde Bailey Scholars (BSP) integrated learning/self-directed courses or modular programming. These experiences would be facilitated by a faculty member, but inquiry and assessment are student led. Alternatively, you can develop learning experiences to enhance an existing course or curriculum. You may also be interested in giving your students the opportunity to facilitate place-based informal learning for youth in the local community.Next Steps: Have Fun. Explore Nature. Get to Know Us!

We invite your ideas and input for designing meaningful experiences at CMERC. Collaborators who are selected for our Fall 2022 cohort will receive $2,000 to support their participation. To explore how you can partner with CMERC, contact Jeno Rivera, Center Educational Program Development Leader at jeno@msu.edu

Deadline to apply: June 15th, 2022.

You are invited to incorporate nature into courses and create learner‐centered experiences at CMERC (pronounced ‘see‐merk’), the Corey Marsh Ecological Research Center. CMERC is a 350‐acre ecological research center located 20 minutes from MSU campus in Bath Township, Michigan. It is a place for making scientific discoveries and integrating the arts and sciences in a collaborative, interdisciplinary, and inclusive space. CMERC welcomes educators, researchers, and citizens across MSU to explore, co‐create, facilitate and grow experiential courses for students.

CMERC seeks faculty and academic staff collaborators to develop learning experiences that will bring together educators, students, and community members to explore and learn from this vibrant ecological field site. MSU faculty and staff from across campus interested in this funded opportunity to join a SoTL Fellowship in land-based learning can connect with Jeno Rivera, Center Educational Program Development Leader at jeno@msu.edu.What is Corey Marsh (CMERC)?

CMERC is more than a physical place. It is a space that offers meaningful place-based experiences.CMERC was once MSU’s Muck Soils Research Center and operated from 1941 – 2012. In 2018, Fisheries and Wildlife associate professor Jen Owen, with the support of MSU AgBioResearch, led the reimagined CMERC into a place for integrating ecosystem science research with student learning and community engagement. In addition to training MSU undergraduate students in field‐based research and science communication, the center aims to promote better land stewardship practices and the relevance of science to society. While still early in its development as an AgBioResearch site, CMERC has been engaging in a people-centered approach to the planning, design and management of the space. CMERC foresees a collaborative process transforming the space to a place that engages a diverse community – internal and external to the university in scientific discovery.Location of Corey Marsh Ecological Research Center in Bath TownshipHow can I contribute?

Given the unique opportunity CMERC provides to enhance student learning, we want to make sure that it serves a diverse student community that spans disciplines and units. We want educators in our SoTL Fellowship in land-based learning to reflect that diversity and help develop curriculum that will foster collaboration among students and serve to integrate arts and humanities with sciences. Consider these examples of possible learning experiences at CMERC:

Edible and Medicinal Plants – for humans and wildlife. What is good for humans vs. wildlife? What grows in muck soils? How can ecological restoration efforts incorporate edible plants? What is missing that was likely at CMERC in the past?

Trails – People – Nature – Wildlife: How does trail design enhance natural experiences and maintain integrity of the ecosystem? What informs the development of a trail?

Land Grant or Land Grab?: Who was here before us? How did this land become a part of the land-grant system? How can this land honor those who used it in the past, present, and the future?

Agriculture and Natural Resources – how can we document and understand how historic land-use affects ecosystem integrity now and in the future?

CMERC actively seeks MSU faculty and staff interested in designing and facilitating an interdisciplinary, learner-centered, sense-making experience built on the resources of CMERC. This curricular/co-curricular programming will be titled Lessons from Nature: Stories from CMERC. We envision that the learning inquiries would be co-created by faculty and students together. More specifically, the lessons will be shaped as a studio experience that is akin to Liberty Hyde Bailey Scholars (BSP) integrated learning/self-directed courses or modular programming. These experiences would be facilitated by a faculty member, but inquiry and assessment are student led. Alternatively, you can develop learning experiences to enhance an existing course or curriculum. You may also be interested in giving your students the opportunity to facilitate place-based informal learning for youth in the local community.Next Steps: Have Fun. Explore Nature. Get to Know Us!

We invite your ideas and input for designing meaningful experiences at CMERC. Collaborators who are selected for our Fall 2022 cohort will receive $2,000 to support their participation. To explore how you can partner with CMERC, contact Jeno Rivera, Center Educational Program Development Leader at jeno@msu.edu

Deadline to apply: June 15th, 2022.

Authored by:

Ellie Louson

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Corey Marsh Ecological Research Center: Create a unique place-based teaching and learning experience

Work with us to create a unique teaching and learning experience at...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, May 16, 2022