We found 347 results that contain "instructors"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

D2L: Customize Your Overview Page

One of the key areas in D2L is the Content section. While instructors create and organize most of the content, there are three sections that appear automatically at the top: Overview, Bookmarks, and Course Schedule.

"Bookmarks" show pages a student has chosen to save.

"Course Schedule" displays calendar items like quiz due dates.

"Overview" is fully customizable, and it’s the first item students see when they enter the Content area.

Why customize your Overview page?

If left blank, the Overview tab won’t appear for students. But adding anything—text or a file—makes it visible.

A personalized overview sets the tone for your course. It can be as simple as a welcome note or as creative as an infographic-style syllabus.

It offers a central place to greet students, direct them to important materials, or give a visual summary of the course.

How do you customize your Overview?

Go to the Content section of your course.

Click on “Overview” in the left-hand navigation pane.

From here, you have two primary options:

Add a written message (e.g., a welcome note or instructions).

Upload a file using the “Add Attachment” button. Note that PDFs appear in an embedded preview window.

You can also do both—include a message and attach a file.

What can you include?

Your Overview page can be as simple or creative as you’d like. Consider:

A brief, friendly welcome note

A short course description

A link to your syllabus

Instructions on how to get started

A welcome graphic

Using a graphic syllabus:

Want to add a creative, visual element? Some instructors choose to use a graphic syllabus: a visual representation of the course structure, themes, or schedule. These can help students grasp big-picture ideas quickly and may be more engaging than text alone.

To use one:

Search online for "graphic syllabus" to view a variety of examples and instructions

Design a graphic or PDF infographic of your syllabus

Make sure it’s accessible (e.g., clear text, high contrast, screen reader-friendly)

Upload it using “Add Attachment” on the Overview page

Programs you can use to create a graphic syllabus:

Canva – Free and user-friendly with templates for infographics, flyers, and syllabi.

PowerPoint – Familiar to many and great for layout flexibility. Save as PDF.

Google Slides – Web-based alternative to PowerPoint, also exportable to PDF.

Adobe Express – Ideal for polished, visual designs; includes free and paid options.

Piktochart – A tool specifically for infographics; allows for easy drag-and-drop design.

Tip: If you go this route, be sure to link to the Overview in your Welcome Announcement so students see it right away (announcements are located on the homepage).

Learn more about accessible design by reading the article "What a cool syllabus... but is it accessible?" by Teresa Thompson.

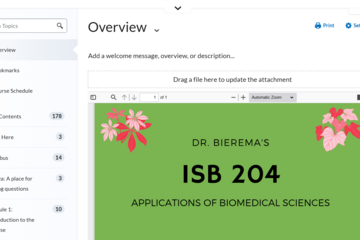

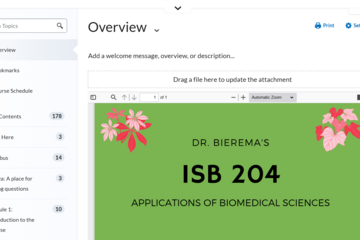

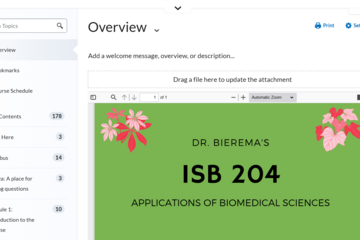

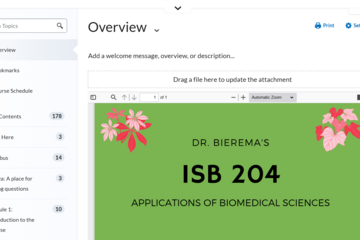

Below is a screenshot of my overview page, in which I created an infographic to represent the course. The infographic is an accessible PDF file, so it appears in a preview window that they can scroll through.

Final Tips

Preview in Student View to confirm what students will see.

Avoid changes after the course begins, unless necessary, and communicate them clearly.

Some attachments (like "Access Google Workspace") may not display even if added—always test in advance.

"Bookmarks" show pages a student has chosen to save.

"Course Schedule" displays calendar items like quiz due dates.

"Overview" is fully customizable, and it’s the first item students see when they enter the Content area.

Why customize your Overview page?

If left blank, the Overview tab won’t appear for students. But adding anything—text or a file—makes it visible.

A personalized overview sets the tone for your course. It can be as simple as a welcome note or as creative as an infographic-style syllabus.

It offers a central place to greet students, direct them to important materials, or give a visual summary of the course.

How do you customize your Overview?

Go to the Content section of your course.

Click on “Overview” in the left-hand navigation pane.

From here, you have two primary options:

Add a written message (e.g., a welcome note or instructions).

Upload a file using the “Add Attachment” button. Note that PDFs appear in an embedded preview window.

You can also do both—include a message and attach a file.

What can you include?

Your Overview page can be as simple or creative as you’d like. Consider:

A brief, friendly welcome note

A short course description

A link to your syllabus

Instructions on how to get started

A welcome graphic

Using a graphic syllabus:

Want to add a creative, visual element? Some instructors choose to use a graphic syllabus: a visual representation of the course structure, themes, or schedule. These can help students grasp big-picture ideas quickly and may be more engaging than text alone.

To use one:

Search online for "graphic syllabus" to view a variety of examples and instructions

Design a graphic or PDF infographic of your syllabus

Make sure it’s accessible (e.g., clear text, high contrast, screen reader-friendly)

Upload it using “Add Attachment” on the Overview page

Programs you can use to create a graphic syllabus:

Canva – Free and user-friendly with templates for infographics, flyers, and syllabi.

PowerPoint – Familiar to many and great for layout flexibility. Save as PDF.

Google Slides – Web-based alternative to PowerPoint, also exportable to PDF.

Adobe Express – Ideal for polished, visual designs; includes free and paid options.

Piktochart – A tool specifically for infographics; allows for easy drag-and-drop design.

Tip: If you go this route, be sure to link to the Overview in your Welcome Announcement so students see it right away (announcements are located on the homepage).

Learn more about accessible design by reading the article "What a cool syllabus... but is it accessible?" by Teresa Thompson.

Below is a screenshot of my overview page, in which I created an infographic to represent the course. The infographic is an accessible PDF file, so it appears in a preview window that they can scroll through.

Final Tips

Preview in Student View to confirm what students will see.

Avoid changes after the course begins, unless necessary, and communicate them clearly.

Some attachments (like "Access Google Workspace") may not display even if added—always test in advance.

Authored by:

Andrea Bierema

Posted on: #iteachmsu

D2L: Customize Your Overview Page

One of the key areas in D2L is the Content section. While instructo...

Authored by:

Thursday, Jun 12, 2025

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

How can a first-year writing course help to create 21st century STEM students with foundations for interdisciplinary inquiry? Could such as curriculum engage STEM students in knowledge production in ways that help to acculturate them as collaborative, ethical, and empathetic learners? Bringing together insights from writing pedagogy, work on critical science literacy, and science studies, this round-table is hosted by the collaborative team leading an effort to rethink the first year writing course required of all students at Lyman Briggs College, MSU's residential college for STEM students. A major goal of the curriculum redesign is to develop science studies-inspired writing assignments that foster reflective experiential learning about the nature of science. The purpose of this approach is not only to demonstrate the value of inquiry in science studies (history, philosophy, and sociology of science) to STEM students as they pursue their careers, but to foster diverse inclusion in science by demystifying key aspects of scientific culture and its hidden curriculum for membership. Following the guidance of critical pedagogy (e.g. bell hooks), we aim to use the context of first-year writing instruction as an opportunity for critical reflection and empowerment. The roundtable describes how the instructional team designed the first-year curriculum and adapted it to teaching online during the pandemic, and shares data on lessons learned by both the instructor team and our students. We invite participants to think with us as we continue to iteratively develop and assess the curriculum.To access a PDF version of the "Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies" poster, click here. Description of Poster:

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

Marisa Brandt, HPS Lyman Briggs College & June Oh, English

Project Overview: Reimagining LB 133

Lyman Briggs College aims to provide a high quality science education to diverse students by teaching science in social, human, and global contexts. LB 133: Science & Culture fulfills the Tier 1 writing requirement for 80-85% of LBC students. Starting in F19, we implemented a new, collaboratively developed and taught cohort model of the LB 133 curriculum in order to take advantage of opportunity to foster a community of inquiry, inclusion, and curiosity.

First year college writing and literacy courses aim to give students skills to communicate and evaluate information in their own fields and beyond. While teaching important writing skills, LB 133 focuses on developing students’ science literacy by encouraging them to enact a subject position of a socially engaged science professional in training. LB 133 was designed based on ideas of HPS.

History, Philosophy, and Sociology (HPS) or “science studies” is an interdisciplinary field that studies science in context, often extended to include medicine, technology, and other sites of knowledge-production. LB 133 centers inquiry into relations of science and culture. One way HPS can help students succeed in STEM is by fostering inclusion. In LB 133, this occurs through demystifying scientific culture and hidden curriculum through authentic, project-based inquiry.

Like WRAC 110, LB 133 is organized around five writing projects. Each project entails a method of inquiry into science as a social, human practice and teaches them to write first as a form of sense-making about their data. (Column 2) Then, students develop writing projects to communicate what they have learned to non-scientific audiences.

Research Questions:

How did their conceptions of science change?[Text Wrapping Break] 2. Did their writing improve?[Text Wrapping Break] 3. What did they see as the most important ideas and skills they would take from the course?[Text Wrapping Break] 4. Did they want more HPS at LBC?

Data Collection:

[Text Wrapping Break]1. Analysis of the beginning and end of course Personal Writing assessments. [Text Wrapping Break]2. End of term survey. [Text Wrapping Break]3. Answers to course reflection questions.

Selected Results: See Column 3.

Conclusions: The new model seems successful! Students reported finding 133 surprisingly enjoyable and educational, for many reasons. Many felt motivated to write about science specifically, saw communication as valuable scientific skill. Most felt their writing improved and learned more than anticipated. Most learned and valued key HPS concepts and wanted to learn more about diversity in scientific cultures, and wanted to continue HPS education in LBC to do so.

Column 2 - Course Structure: Science & Culture

Assessment

Science Studies Content[Text Wrapping Break]Learning Goals

Literacy & Writing Skills Learning Goals

Part 1 - Cultures of Science

Personal Writing 1: Personal Statement [STEM Ed Op-ed][Text Wrapping Break]Short form writing from scientific subject position.

Reflect on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Diagnostic for answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Scientific Sites Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of how a local lab produces knowledge.

Understand scientific practice, reasoning, and communication in its diverse social, material, and cultural contexts. Demystify labs and humanize scientists.

Making observational field notes. Reading scientific papers.

Peer review. Claim, evidence, reasoning. Writing analytical essays based on observation.

Part 2 - Science in Culture

Unpacking a Fact Poster

Partner project assessing validity of a public scientific claim.

Understand the mediation of science and how to evaluate scientific claims. Identify popular conceptions of science and contrast these with scientists’ practices.

Following sources upstream. Comparing sources.

APA citation style.

Visual display of info on a poster.

Perspectives Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of a debate concerning science in Michigan.

Identify and analyze how diverse stakeholders are included in and/or excluded from science. Recognize value of diverse perspective.

Find, use, and correctly cite primary and scholarly secondary sources from different stakeholder perspectives.

Learn communicating to a broader audience in an online platform.

Personal Writing 2: Letter + PS Revision[Text Wrapping Break]Sharing a course takeaway with someone.

Reflect again on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Final assessment of answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Weekly Formative Assessments

Discussion Activities Pre-meeting writing about the readings

Reflect on prompted aspects of science and culture

Writing as critical inquiry.

Note-taking.

Preparation for discussion.

Curiosity Colloquium responses

200 words reflecting on weekly speaker series

Exposure to college, campus, and academic guests—including diverse science professionals— who share their curiosity and career story.

Writing as reflection on presentations and their personal value.

Some presenters share research and writing skills.

Column 3 - Results

Results from Personal Writing

Fall 19: There were largely six themes the op-ed assignments discussed. Majority of students chose to talk about the value of science in terms of its ubiquity, problem-solving skills and critical thinking skills, and the way it prompts technological innovation.

Fall 21: Students largely focused on 1. the nature of science as a product of human labor research embedded with many cultural issues, and 2. science as a communication and how scientists can gain public trust (e.g., transparency, collaboration, sharing failure.)

F19 & S20 Selected Survey Results

108 students responding.The full report here.

92.5% reported their overall college writing skills improved somewhat or a lot.

76% reported their writing skills improved somewhat or a lot more than they expected.

89% reported planning to say in LBC.

Selected Course Reflection Comments

The most impactful things students report learning at end of semester.

Science and Culture: Quotes: “how scientific knowledge is produced” “science is inherently social” “how different perspectives . . . impact science” “writing is integral to the scientific community as a method of sharing and documenting scientific research and discoveries”

Writing: Quotes: “a thesis must be specific and debatable” “claim, evidence, and reasoning” “it takes a long time to perfect.” Frequently mentioned skills: Thesis, research skill (citation, finding articles and proper sources), argument (evidence), structure and organization skills, writing as a (often long and arduous) process, using a mentor text, confidence.

What do you want to learn more about after this course?

“How culture(s) and science coexist, and . . . how different cultures view science”

“Gender and minority disparities in STEM” “minority groups in science and how their cultures impact how they conduct science” “different cultures in science instead of just the United States” “how to write scientific essays”

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

Marisa Brandt, HPS Lyman Briggs College & June Oh, English

Project Overview: Reimagining LB 133

Lyman Briggs College aims to provide a high quality science education to diverse students by teaching science in social, human, and global contexts. LB 133: Science & Culture fulfills the Tier 1 writing requirement for 80-85% of LBC students. Starting in F19, we implemented a new, collaboratively developed and taught cohort model of the LB 133 curriculum in order to take advantage of opportunity to foster a community of inquiry, inclusion, and curiosity.

First year college writing and literacy courses aim to give students skills to communicate and evaluate information in their own fields and beyond. While teaching important writing skills, LB 133 focuses on developing students’ science literacy by encouraging them to enact a subject position of a socially engaged science professional in training. LB 133 was designed based on ideas of HPS.

History, Philosophy, and Sociology (HPS) or “science studies” is an interdisciplinary field that studies science in context, often extended to include medicine, technology, and other sites of knowledge-production. LB 133 centers inquiry into relations of science and culture. One way HPS can help students succeed in STEM is by fostering inclusion. In LB 133, this occurs through demystifying scientific culture and hidden curriculum through authentic, project-based inquiry.

Like WRAC 110, LB 133 is organized around five writing projects. Each project entails a method of inquiry into science as a social, human practice and teaches them to write first as a form of sense-making about their data. (Column 2) Then, students develop writing projects to communicate what they have learned to non-scientific audiences.

Research Questions:

How did their conceptions of science change?[Text Wrapping Break] 2. Did their writing improve?[Text Wrapping Break] 3. What did they see as the most important ideas and skills they would take from the course?[Text Wrapping Break] 4. Did they want more HPS at LBC?

Data Collection:

[Text Wrapping Break]1. Analysis of the beginning and end of course Personal Writing assessments. [Text Wrapping Break]2. End of term survey. [Text Wrapping Break]3. Answers to course reflection questions.

Selected Results: See Column 3.

Conclusions: The new model seems successful! Students reported finding 133 surprisingly enjoyable and educational, for many reasons. Many felt motivated to write about science specifically, saw communication as valuable scientific skill. Most felt their writing improved and learned more than anticipated. Most learned and valued key HPS concepts and wanted to learn more about diversity in scientific cultures, and wanted to continue HPS education in LBC to do so.

Column 2 - Course Structure: Science & Culture

Assessment

Science Studies Content[Text Wrapping Break]Learning Goals

Literacy & Writing Skills Learning Goals

Part 1 - Cultures of Science

Personal Writing 1: Personal Statement [STEM Ed Op-ed][Text Wrapping Break]Short form writing from scientific subject position.

Reflect on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Diagnostic for answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Scientific Sites Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of how a local lab produces knowledge.

Understand scientific practice, reasoning, and communication in its diverse social, material, and cultural contexts. Demystify labs and humanize scientists.

Making observational field notes. Reading scientific papers.

Peer review. Claim, evidence, reasoning. Writing analytical essays based on observation.

Part 2 - Science in Culture

Unpacking a Fact Poster

Partner project assessing validity of a public scientific claim.

Understand the mediation of science and how to evaluate scientific claims. Identify popular conceptions of science and contrast these with scientists’ practices.

Following sources upstream. Comparing sources.

APA citation style.

Visual display of info on a poster.

Perspectives Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of a debate concerning science in Michigan.

Identify and analyze how diverse stakeholders are included in and/or excluded from science. Recognize value of diverse perspective.

Find, use, and correctly cite primary and scholarly secondary sources from different stakeholder perspectives.

Learn communicating to a broader audience in an online platform.

Personal Writing 2: Letter + PS Revision[Text Wrapping Break]Sharing a course takeaway with someone.

Reflect again on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Final assessment of answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Weekly Formative Assessments

Discussion Activities Pre-meeting writing about the readings

Reflect on prompted aspects of science and culture

Writing as critical inquiry.

Note-taking.

Preparation for discussion.

Curiosity Colloquium responses

200 words reflecting on weekly speaker series

Exposure to college, campus, and academic guests—including diverse science professionals— who share their curiosity and career story.

Writing as reflection on presentations and their personal value.

Some presenters share research and writing skills.

Column 3 - Results

Results from Personal Writing

Fall 19: There were largely six themes the op-ed assignments discussed. Majority of students chose to talk about the value of science in terms of its ubiquity, problem-solving skills and critical thinking skills, and the way it prompts technological innovation.

Fall 21: Students largely focused on 1. the nature of science as a product of human labor research embedded with many cultural issues, and 2. science as a communication and how scientists can gain public trust (e.g., transparency, collaboration, sharing failure.)

F19 & S20 Selected Survey Results

108 students responding.The full report here.

92.5% reported their overall college writing skills improved somewhat or a lot.

76% reported their writing skills improved somewhat or a lot more than they expected.

89% reported planning to say in LBC.

Selected Course Reflection Comments

The most impactful things students report learning at end of semester.

Science and Culture: Quotes: “how scientific knowledge is produced” “science is inherently social” “how different perspectives . . . impact science” “writing is integral to the scientific community as a method of sharing and documenting scientific research and discoveries”

Writing: Quotes: “a thesis must be specific and debatable” “claim, evidence, and reasoning” “it takes a long time to perfect.” Frequently mentioned skills: Thesis, research skill (citation, finding articles and proper sources), argument (evidence), structure and organization skills, writing as a (often long and arduous) process, using a mentor text, confidence.

What do you want to learn more about after this course?

“How culture(s) and science coexist, and . . . how different cultures view science”

“Gender and minority disparities in STEM” “minority groups in science and how their cultures impact how they conduct science” “different cultures in science instead of just the United States” “how to write scientific essays”

Authored by:

Marisa Brandt & June Oh

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

How can a first-year writing course help to create 21st century STE...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Thursday, May 6, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

December collaborative tools training from MSU IT

Check out December’s courses about collaborative tools training, available at no cost to all students, faculty, and staff. Visit SpartansLearn for more information and to register.

Outlook – Calendar Basics

December 8, 1:30 p.m. (Virtual)

Discover the full potential of Outlook calendar with our comprehensive training. From setting up to managing your schedule like a pro, this course covers it all. You'll learn how to set your email for "Out of Office" and share your calendar with ease. Plus, our hands-on experience with the Scheduling Assistant and other tools will help you streamline your scheduling process like never before. Join us now and take your productivity to the next level!

What participants are saying...

“This course explained how to do simple tasks that will help me streamline my workflows."

To register for the following virtual and in-person instructor-led training courses go to SpartansLearn.

Microsoft Teams – Getting Started

December 5, 10:00 a.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

Teams is one of the best tools at MSU for effective communication and collaboration. Join us as we dive into the basics and share how to chat and host meetings with individuals, groups, and entire teams.

Zoom – Getting Started

December 5, 1:30 p.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

A great tool for scheduling and hosting virtual meetings, learn how to access Zoom at MSU and explore its settings.

Microsoft Teams – Meetings

December 7, 10:00 a.m. (Virtual)

Explore the settings, tools, and interactive options within a Teams video call meeting. Learn how to schedule and join a meeting, use backgrounds, utilize breakout rooms, and record meetings.

Microsoft OneDrive – Getting Started

December 11, 10:00 a.m. (Virtual)

OneDrive is a great place to store files in the cloud, share documents, and ensure document security. Learn about the basics in this entry level course.

Microsoft Forms – Creating Forms and Surveys

December 15, 10:00 a.m. (Virtual)

December 19, 1:30 p.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

Forms can help survey classmates, students, coworkers, or any group where feedback is needed. Learn how to create forms and surveys, format, branch, collect data, and share with others.

Microsoft OneDrive- Working with OneDrive

December 19, 10:00 a.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

Expanding on the basics of OneDrive, learn more about this great storage tool. Discover navigation strategies, explore the desktop app settings and options, manage accessibility of files and folders, and more.

Can’t attend a live course? Each is available on-demand to watch anytime at SpartansLearn.

Weekly office hours are available for those with questions about content shared in the courses. Find the schedule at SpartansLearn.

For any other questions about technology training, please contact train@msu.edu.

Outlook – Calendar Basics

December 8, 1:30 p.m. (Virtual)

Discover the full potential of Outlook calendar with our comprehensive training. From setting up to managing your schedule like a pro, this course covers it all. You'll learn how to set your email for "Out of Office" and share your calendar with ease. Plus, our hands-on experience with the Scheduling Assistant and other tools will help you streamline your scheduling process like never before. Join us now and take your productivity to the next level!

What participants are saying...

“This course explained how to do simple tasks that will help me streamline my workflows."

To register for the following virtual and in-person instructor-led training courses go to SpartansLearn.

Microsoft Teams – Getting Started

December 5, 10:00 a.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

Teams is one of the best tools at MSU for effective communication and collaboration. Join us as we dive into the basics and share how to chat and host meetings with individuals, groups, and entire teams.

Zoom – Getting Started

December 5, 1:30 p.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

A great tool for scheduling and hosting virtual meetings, learn how to access Zoom at MSU and explore its settings.

Microsoft Teams – Meetings

December 7, 10:00 a.m. (Virtual)

Explore the settings, tools, and interactive options within a Teams video call meeting. Learn how to schedule and join a meeting, use backgrounds, utilize breakout rooms, and record meetings.

Microsoft OneDrive – Getting Started

December 11, 10:00 a.m. (Virtual)

OneDrive is a great place to store files in the cloud, share documents, and ensure document security. Learn about the basics in this entry level course.

Microsoft Forms – Creating Forms and Surveys

December 15, 10:00 a.m. (Virtual)

December 19, 1:30 p.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

Forms can help survey classmates, students, coworkers, or any group where feedback is needed. Learn how to create forms and surveys, format, branch, collect data, and share with others.

Microsoft OneDrive- Working with OneDrive

December 19, 10:00 a.m. (In-person, Anthony Hall, Rm 1210)

Expanding on the basics of OneDrive, learn more about this great storage tool. Discover navigation strategies, explore the desktop app settings and options, manage accessibility of files and folders, and more.

Can’t attend a live course? Each is available on-demand to watch anytime at SpartansLearn.

Weekly office hours are available for those with questions about content shared in the courses. Find the schedule at SpartansLearn.

For any other questions about technology training, please contact train@msu.edu.

Posted by:

Caitlin Clover

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

How Video Length Affects Student Learning – The Shorter, The Better!

In-Person Lectures vs. Online Instruction

Actively engaging students in the learning process is important for both in-person lectures and for online instruction. The ways in which students engage with the instructor, their peers, and the course materials will vary based on the setting. In-person courses are often confined by the fact that instruction needs to be squeezed into a specific time period, which can result in there being a limited amount of time for students to perform group work or to actively think about the concepts they are learning. Alternatively, with online instruction, there is often more freedom (especially for an asynchronous course) on how you can present materials and structure the learning environment.

Currently, many instructors are faced with the challenge of adapting their in-person courses into an online format. How course materials are adapted into an online format are going to differ from course to course – however, a common practice shared across courses is to create lecture recordings or videos for students to watch. The format and length of these videos play an important role in the learning experience students have within a course. The ways in which students engage with a longer video recording is going to be much different than how students engage with multiple shorter videos. Below are some of the important reasons why shorter videos can enhance student learning when compared to longer videos.

More Opportunities for Students to Actively Engage with the Material

Decades of research on how people learn has shown that active learning (in comparison to more passive approaches, such as direct instruction or a traditional lecture) enhances student performance (Freeman et. al., 2014). While “active learning” can often be a nebulous phrase that has different meanings, active learning can be broadly thought of as any activity in which a learner is metacognitively thinking about and applying knowledge to accomplish some goal or task. Providing multiple opportunities for students to engage in these types of activities can help foster a more meaningful and inclusive learning environment for students. This is especially important for online instruction as students may feel isolated or have a difficult time navigating their learning within a virtual environment.

One of the biggest benefits of creating a series of shorter videos compared to creating one long video is that active learning techniques and activities can be more easily utilized and interspersed throughout a lesson. For example, if you were to record a video of a traditional lecture period, your video would be nearly an hour in length, and it would likely cover multiple important topics within that time period. Creating opportunities to actively engage students throughout an hour-long video is difficult and can result in students feeling overwhelmed.

Conversely, one of the affordances of online instruction is that lectures can be broken down into a series of smaller video lessons and activities. By having shorter videos with corresponding activities, students are going to spend more time actively thinking about and applying their understanding of concepts throughout a lesson. This in turn can promote metacognition by getting students to think about their thinking after each short video rather than at the end of a long video that covers multiple topics.

Additionally, concepts often build upon one another, and it is critical that students develop a solid foundation of prior knowledge before moving onto more complex topics. When you create multiple short videos and activities, it can be easier to get a snapshot of how students conceptualize different topics as they are learning it. This information can help both you as an instructor and your students become better aware of when they are having difficulties so that issues can be addressed before moving onto more complex topics. With longer videos, students may be confused on concepts discussed at the beginning of the video, which can then make it difficult for them to understand subsequent concepts.

Overall, chunking a longer video into multiple shorter videos is a simple technique you can use to create more meaningful learning opportunities in a virtual setting. Short videos, coupled with corresponding activities, is a powerful pedagogical approach to enhance student learning.

Reducing Cognitive Load

Another major benefit of having multiple shorter videos instead of one longer video is that it can reduce the cognitive load that students experience when engaging with the content. Learning is a process that requires the brain to adapt, develop, and ultimately form new neural connections in response to stimuli (National Academies of Sciences, 2018). If a video is long and packed with content, developing a meaningful understanding of concepts can be quite difficult. Even if the content is explained in detail (which many people think of as “good instruction”), students simply do not have enough time to process and critically think about the content they are learning. When taking in various stimuli and trying to comprehend multiple concepts, this can result in students feeling anxious and overwhelmed. Having time to self-reflect is one of the most important factors to promoting a deeper, more meaningful learning experience. Unfortunately, long video lectures provide few opportunities (even when done well!) for students to engage in these types of thinking and doing.

Additionally, an unintended drawback of long videos is that the listener can be lulled into a false sense of understanding. For example, have you ever watched a live lecture or an educational video where you followed along and felt like you understood the material, but then after when you went to apply this knowledge, you realized that you forgot or did not understand the content as well as you thought? Everyone has experienced this phenomenon in some form or another. As students watch long video lectures, especially lectures that have clear explanations of the content, they may get a false sense of how well they understand the material. This can result in students overestimating their ability and grasp of foundational ideas, which in turn, can make future learning more difficult as subsequent knowledge will be built upon a faulty base.

Long lecture videos are also more prone to having extraneous information or tangential discussions throughout. This additional information may cause students to shift their cognitive resources away from the core course content, resulting in a less meaningful learning experience (Mayer & Moreno, 2003). Breaking a long video into multiple shorter videos can reduce the cognitive load students may experience and it can create more opportunities for them to self-reflect on what they are learning.

More Engaging for Students

Another important factor to think about is how video length affects student engagement. A study by Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014) looked at how different forms of video production affected student engagement when watching videos. Two of their main findings were that (1) shorter videos improve student engagement, and that (2) recordings of traditional lectures are less engaging compared to digital tablet drawing or PowerPoint slide presentations. These findings show how it is not only important to record shorter videos, but that simply recording a traditional lecture and splicing it into smaller videos will not result in the most engaging experience for students.

When distilling a traditional lecture into a series of shorter videos, it is important to think about the pedagogical techniques you would normally use in the classroom and how these approaches might translate to an online setting. Identifying how these approaches might be adapted into a video recording can help create a more engaging experience for students in your course.

Overall, the length of lecture videos and the ways in which they are structured directly impacts how students learn in a virtual setting. Recording short, interactive videos, as opposed to long lecture videos, is a powerful technique you can use to enhance student learning and engagement.

References

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50).

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 43-52.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press.

Actively engaging students in the learning process is important for both in-person lectures and for online instruction. The ways in which students engage with the instructor, their peers, and the course materials will vary based on the setting. In-person courses are often confined by the fact that instruction needs to be squeezed into a specific time period, which can result in there being a limited amount of time for students to perform group work or to actively think about the concepts they are learning. Alternatively, with online instruction, there is often more freedom (especially for an asynchronous course) on how you can present materials and structure the learning environment.

Currently, many instructors are faced with the challenge of adapting their in-person courses into an online format. How course materials are adapted into an online format are going to differ from course to course – however, a common practice shared across courses is to create lecture recordings or videos for students to watch. The format and length of these videos play an important role in the learning experience students have within a course. The ways in which students engage with a longer video recording is going to be much different than how students engage with multiple shorter videos. Below are some of the important reasons why shorter videos can enhance student learning when compared to longer videos.

More Opportunities for Students to Actively Engage with the Material

Decades of research on how people learn has shown that active learning (in comparison to more passive approaches, such as direct instruction or a traditional lecture) enhances student performance (Freeman et. al., 2014). While “active learning” can often be a nebulous phrase that has different meanings, active learning can be broadly thought of as any activity in which a learner is metacognitively thinking about and applying knowledge to accomplish some goal or task. Providing multiple opportunities for students to engage in these types of activities can help foster a more meaningful and inclusive learning environment for students. This is especially important for online instruction as students may feel isolated or have a difficult time navigating their learning within a virtual environment.

One of the biggest benefits of creating a series of shorter videos compared to creating one long video is that active learning techniques and activities can be more easily utilized and interspersed throughout a lesson. For example, if you were to record a video of a traditional lecture period, your video would be nearly an hour in length, and it would likely cover multiple important topics within that time period. Creating opportunities to actively engage students throughout an hour-long video is difficult and can result in students feeling overwhelmed.

Conversely, one of the affordances of online instruction is that lectures can be broken down into a series of smaller video lessons and activities. By having shorter videos with corresponding activities, students are going to spend more time actively thinking about and applying their understanding of concepts throughout a lesson. This in turn can promote metacognition by getting students to think about their thinking after each short video rather than at the end of a long video that covers multiple topics.

Additionally, concepts often build upon one another, and it is critical that students develop a solid foundation of prior knowledge before moving onto more complex topics. When you create multiple short videos and activities, it can be easier to get a snapshot of how students conceptualize different topics as they are learning it. This information can help both you as an instructor and your students become better aware of when they are having difficulties so that issues can be addressed before moving onto more complex topics. With longer videos, students may be confused on concepts discussed at the beginning of the video, which can then make it difficult for them to understand subsequent concepts.

Overall, chunking a longer video into multiple shorter videos is a simple technique you can use to create more meaningful learning opportunities in a virtual setting. Short videos, coupled with corresponding activities, is a powerful pedagogical approach to enhance student learning.

Reducing Cognitive Load

Another major benefit of having multiple shorter videos instead of one longer video is that it can reduce the cognitive load that students experience when engaging with the content. Learning is a process that requires the brain to adapt, develop, and ultimately form new neural connections in response to stimuli (National Academies of Sciences, 2018). If a video is long and packed with content, developing a meaningful understanding of concepts can be quite difficult. Even if the content is explained in detail (which many people think of as “good instruction”), students simply do not have enough time to process and critically think about the content they are learning. When taking in various stimuli and trying to comprehend multiple concepts, this can result in students feeling anxious and overwhelmed. Having time to self-reflect is one of the most important factors to promoting a deeper, more meaningful learning experience. Unfortunately, long video lectures provide few opportunities (even when done well!) for students to engage in these types of thinking and doing.

Additionally, an unintended drawback of long videos is that the listener can be lulled into a false sense of understanding. For example, have you ever watched a live lecture or an educational video where you followed along and felt like you understood the material, but then after when you went to apply this knowledge, you realized that you forgot or did not understand the content as well as you thought? Everyone has experienced this phenomenon in some form or another. As students watch long video lectures, especially lectures that have clear explanations of the content, they may get a false sense of how well they understand the material. This can result in students overestimating their ability and grasp of foundational ideas, which in turn, can make future learning more difficult as subsequent knowledge will be built upon a faulty base.

Long lecture videos are also more prone to having extraneous information or tangential discussions throughout. This additional information may cause students to shift their cognitive resources away from the core course content, resulting in a less meaningful learning experience (Mayer & Moreno, 2003). Breaking a long video into multiple shorter videos can reduce the cognitive load students may experience and it can create more opportunities for them to self-reflect on what they are learning.

More Engaging for Students

Another important factor to think about is how video length affects student engagement. A study by Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014) looked at how different forms of video production affected student engagement when watching videos. Two of their main findings were that (1) shorter videos improve student engagement, and that (2) recordings of traditional lectures are less engaging compared to digital tablet drawing or PowerPoint slide presentations. These findings show how it is not only important to record shorter videos, but that simply recording a traditional lecture and splicing it into smaller videos will not result in the most engaging experience for students.

When distilling a traditional lecture into a series of shorter videos, it is important to think about the pedagogical techniques you would normally use in the classroom and how these approaches might translate to an online setting. Identifying how these approaches might be adapted into a video recording can help create a more engaging experience for students in your course.

Overall, the length of lecture videos and the ways in which they are structured directly impacts how students learn in a virtual setting. Recording short, interactive videos, as opposed to long lecture videos, is a powerful technique you can use to enhance student learning and engagement.

References

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50).

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 43-52.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press.

Authored by:

Christopher J. Minter

Posted on: #iteachmsu

How Video Length Affects Student Learning – The Shorter, The Better!

In-Person Lectures vs. Online Instruction

Actively engaging student...

Actively engaging student...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, Sep 2, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Crystal Eustice's Educator Story

This week, we are featuring Dr. Crystal Eustice, Assistant Professor of Practice, Academic Adviser, and Internship Coordinator in MSU’s Department of Community Sustainability. Dr. Eustice was recognized via iteach.msu.edu's Thank and Educator Initiative! We encourage MSU community members to nominate high-impact Spartan educators (via our Thank an Educator form) regularly!

Read more about Dr. Eustice’s perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by her responses!

You were recognized via the Thank an Educator Initiative. In one word, what does being an educator mean to you?

Leadership

Share with me what this word/quality looks like in your practice?

I use the word “leadership”, because leadership in itself takes many different forms depending on the person and the context. To me, this is what being an educator means as well. To meet students where they are, to be what the students need to learn, to instill curiosity, to guide students in developing new skills...

Have your ideas on this changed over time? if so how?

Over time, being an educator has shifted from feeling like I always need to know the answer for my students, to allowing the questions (theirs and mine) to guide us in exploring solutions. It’s shifted to me passing leadership in the classroom over to the students as they build confidence and start pursuing answers and activities that guide their own learning.

Tell me more about your educational “setting.” This can include, but not limited to departmental affiliations, community connections, co-instructors, and students. (Aka, where do you work?)

I am faculty member in the Department of Community Sustainability (CSUS) in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. I also serve as an Academic Advisor for 2 of our 3 majors in CSUS, as well as the Internship Coordinator.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role?

Wearing three hats in my position often creates challenges in terms of how to best engage students in all three areas in authentic ways and build relationships with my students.

Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

To show students support and engage them, I blend all three roles within my job regardless of what “hat” I’m wearing. Meaning, when I teach, I work to help build students transferable skills that will benefit them as they pursue and take on professional internships. I also work to communicate advising and employment information with students in my role as educator in the classroom, as well as serving as their internship coordinator, and academic advisor. Largely, supporting student success means supporting the whole student, in multiple ways, and making time and space to do so in my various roles.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

I seek feedback from my students about their experiences in my courses, as well as their overall experiences at MSU (i.e., in other courses). What’s working for them and what’s not; what resources have been most helpful to them, etcetera. This helps me evaluate and improve my leadership in all three of my roles.

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature!

Read more about Dr. Eustice’s perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by her responses!

You were recognized via the Thank an Educator Initiative. In one word, what does being an educator mean to you?

Leadership

Share with me what this word/quality looks like in your practice?

I use the word “leadership”, because leadership in itself takes many different forms depending on the person and the context. To me, this is what being an educator means as well. To meet students where they are, to be what the students need to learn, to instill curiosity, to guide students in developing new skills...

Have your ideas on this changed over time? if so how?

Over time, being an educator has shifted from feeling like I always need to know the answer for my students, to allowing the questions (theirs and mine) to guide us in exploring solutions. It’s shifted to me passing leadership in the classroom over to the students as they build confidence and start pursuing answers and activities that guide their own learning.

Tell me more about your educational “setting.” This can include, but not limited to departmental affiliations, community connections, co-instructors, and students. (Aka, where do you work?)

I am faculty member in the Department of Community Sustainability (CSUS) in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. I also serve as an Academic Advisor for 2 of our 3 majors in CSUS, as well as the Internship Coordinator.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role?

Wearing three hats in my position often creates challenges in terms of how to best engage students in all three areas in authentic ways and build relationships with my students.

Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

To show students support and engage them, I blend all three roles within my job regardless of what “hat” I’m wearing. Meaning, when I teach, I work to help build students transferable skills that will benefit them as they pursue and take on professional internships. I also work to communicate advising and employment information with students in my role as educator in the classroom, as well as serving as their internship coordinator, and academic advisor. Largely, supporting student success means supporting the whole student, in multiple ways, and making time and space to do so in my various roles.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

I seek feedback from my students about their experiences in my courses, as well as their overall experiences at MSU (i.e., in other courses). What’s working for them and what’s not; what resources have been most helpful to them, etcetera. This helps me evaluate and improve my leadership in all three of my roles.

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature!

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Crystal Eustice's Educator Story

This week, we are featuring Dr. Crystal Eustice, Assistant Professo...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Friday, Nov 12, 2021

Posted on: Educator Stories

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Educator Stories: Gary Roloff

This week, we are featuring, Dr. Gary Roloff, Professor and Chair in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. Dr. Roloff was recognized via iteach.msu.edu's Thank and Educator Initiative! We encourage MSU community members to nominate high impact Spartan educators (via our Thank an Educator form) regularly!

Read more about Dr. Roloff’s perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by his responses!

In one word, what does being an educator mean to you?

Empowering

Share with me what this word/quality looks like in your practice?

As an educator, I look to facilitate critical thinking, synthesis of ideas and information, acquisition of contextual knowledge, and informed judgment that ultimately results in empowered, confident decision-making and choices by our students.

Have your ideas on this changed over time? if so how?

My philosophy on this has absolutely changed over time. When I initially started teaching I leaned towards emphasizing contextual knowledge (e.g., why snowshoe hare are white in winter, why pigs turn feral so fast when released into an unconstrained environment), where there was a clear answer that could be assessed for correctness. I quickly realized that guidance for students on synthesizing and integrating contextual knowledge (and other pieces of information) to make informed arguments and decisions was a gap in my learning outcomes. Since then, I’ve worked to correct that deficiency in my course offerings.

Tell me more about your educational “setting.” This can include, but not limited to departmental affiliations, community connections, co-instructors, and students.

I am lucky enough to teach a field-based course in wildlife research and management techniques (I also teach a graduate-level course), which includes a blend of classroom and field experiences. Much of the class is hands-on and outside, and I involve our agency partners like the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and USDA Wildlife Services to teach sections of the class. This professional-student interaction is often a highlight for the students, providing an important opportunity to help build a professional network that is so critical to success. Some students in my class have gone on to work for the agencies that help me teach.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role?

My biggest challenge is reading the classroom early and trying to adjust my delivery of content to the different learning styles that I know occur in the room. As instructors, if we fail to recognize and adjust our content and delivery to appeal to diverse learning styles we are not being fair.

Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

I started implementing a brief survey at the start of the semester in my undergraduate class to gauge personality types. The students work in groups in that class on a semester project that looks for integration and synthesis across the semester. One of my PhD students, as part of her FAST Fellows program, showed that “introverts” were at a significant disadvantage in these types of settings, unless we were able to integrate them into “extrovert” groups from the start. I stopped letting students form groups on their own, as the “introverts” and “extroverts” tended to group together; instead I purposefully mix the personality types to help create a more equitable chance of success for all students in the class.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

Last fall, I changed my standard assessment technique for the mid-term. I used to implement a standard type test, where students identify things and answer questions on paper. This fall I changed the mid-term to a field practical, where I interacted verbally with the students (i.e., an oral exam) and had them show me how to do things and explain their answers. This one-on-one assessment, though time-consuming, gave me a better sense (I believe) of how the students were learning the course content.

What topics or ideas about teaching and learning would you like to see discussed on the iteach.msu.edu platform? Why do you think this conversation is needed at msu?

Efficient, effective ways to teach our students better oral and written communication skills as part of the classes they take.

What are you looking forward to (or excited to be a part of) next semester?

I really miss the energy of campus; I’m hoping we can return to some sense of post-pandemic normalcy soon.

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature! Follow the MSU Hub Twitter account to see other great content from the #iteachmsu Commons as well as educators featured every week during #ThankfulThursdays.

Read more about Dr. Roloff’s perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by his responses!

In one word, what does being an educator mean to you?

Empowering

Share with me what this word/quality looks like in your practice?

As an educator, I look to facilitate critical thinking, synthesis of ideas and information, acquisition of contextual knowledge, and informed judgment that ultimately results in empowered, confident decision-making and choices by our students.

Have your ideas on this changed over time? if so how?

My philosophy on this has absolutely changed over time. When I initially started teaching I leaned towards emphasizing contextual knowledge (e.g., why snowshoe hare are white in winter, why pigs turn feral so fast when released into an unconstrained environment), where there was a clear answer that could be assessed for correctness. I quickly realized that guidance for students on synthesizing and integrating contextual knowledge (and other pieces of information) to make informed arguments and decisions was a gap in my learning outcomes. Since then, I’ve worked to correct that deficiency in my course offerings.

Tell me more about your educational “setting.” This can include, but not limited to departmental affiliations, community connections, co-instructors, and students.

I am lucky enough to teach a field-based course in wildlife research and management techniques (I also teach a graduate-level course), which includes a blend of classroom and field experiences. Much of the class is hands-on and outside, and I involve our agency partners like the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and USDA Wildlife Services to teach sections of the class. This professional-student interaction is often a highlight for the students, providing an important opportunity to help build a professional network that is so critical to success. Some students in my class have gone on to work for the agencies that help me teach.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role?

My biggest challenge is reading the classroom early and trying to adjust my delivery of content to the different learning styles that I know occur in the room. As instructors, if we fail to recognize and adjust our content and delivery to appeal to diverse learning styles we are not being fair.

Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

I started implementing a brief survey at the start of the semester in my undergraduate class to gauge personality types. The students work in groups in that class on a semester project that looks for integration and synthesis across the semester. One of my PhD students, as part of her FAST Fellows program, showed that “introverts” were at a significant disadvantage in these types of settings, unless we were able to integrate them into “extrovert” groups from the start. I stopped letting students form groups on their own, as the “introverts” and “extroverts” tended to group together; instead I purposefully mix the personality types to help create a more equitable chance of success for all students in the class.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

Last fall, I changed my standard assessment technique for the mid-term. I used to implement a standard type test, where students identify things and answer questions on paper. This fall I changed the mid-term to a field practical, where I interacted verbally with the students (i.e., an oral exam) and had them show me how to do things and explain their answers. This one-on-one assessment, though time-consuming, gave me a better sense (I believe) of how the students were learning the course content.

What topics or ideas about teaching and learning would you like to see discussed on the iteach.msu.edu platform? Why do you think this conversation is needed at msu?

Efficient, effective ways to teach our students better oral and written communication skills as part of the classes they take.

What are you looking forward to (or excited to be a part of) next semester?

I really miss the energy of campus; I’m hoping we can return to some sense of post-pandemic normalcy soon.

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature! Follow the MSU Hub Twitter account to see other great content from the #iteachmsu Commons as well as educators featured every week during #ThankfulThursdays.

Authored by:

Kristen Surla

Posted on: Educator Stories

Educator Stories: Gary Roloff

This week, we are featuring, Dr. Gary Roloff, Professor and Chair i...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Feb 22, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Pandemic Pedagogy: Online Learning and Suggestions for Minimizing Student Storms in a Teacup

This poster outlines approximately 20 suggestions to help students navigate online courses more successfully. Even with careful planning and development, the normalization of remote learning has not been without challenges for the students enrolled in our courses. Besides worrying about a stable internet connection, students must confront a steep learning curve and considerable frustration when it comes to completing even the most basic coursework each week. Participation in the ASPIRE and SOIREE programs notwithstanding, and despite our carefully worded syllabi, weekly course modules, project packets, assignment prompts, and the like, students nevertheless experience significant confusion and anxiety when faced with the prospect of leaving the physical classroom behind for the brave new world of the virtual. The reduction of course material by instructors to bite-sized chunks and the opportunity for online collaboration with their classmates do not necessarily mean students greet online learning with open arms. Already entrenched attitudes and habits among many young adults do little to help them as they make the shift to online learning. But there are a number of fairly simple ways that instructors can smooth this rocky road over which students must now travel. The tips I share have emerged and been developed further as part of my own ongoing process to minimize confusion, frustration, and improve levels of engagement, while simultaneously imparting more agency to the students enrolled in my IAH courses here at Michigan State University.To access a PDF of the "Pandemic Pedagogy: Online Learning and Suggestions for Minimizing Student Storms in a Teacup" poster, click here.

Description of the Poster

Pandemic Pedagogy: Online Learning and Suggestions for Minimizing Student Storms in a Teacup

Stokes Schwartz, Center for Integrative Studies in the Arts and Humanities

College of Arts and Letters, Michigan State University

Abstract

The normalization of remote learning during 2020-2021 has not been without challenges for the students enrolled in our courses. Besides worrying about stable internet connections, they must also confront a steep learning curve and considerable frustration when it comes to completing even the most basic coursework each week. Even with instructor participation in the ASPIRE and SOIREE programs, carefully worded syllabi, weekly course modules, project packets, assignment prompts, and etc., students nevertheless experience significant confusion and anxiety when faced with the prospect of leaving the physical classroom behind for the virtual. Our reduction of course material to bite-sized chunks and the opportunity for online collaboration with their classmates via Zoom or Teams do not necessarily mean students greet online learning with open arms. Already entrenched attitudes and habits among many young adults do little to help them either in the shift to online learning. But there are a few fairly simple ways that instructors can smooth the rocky road over which students must travel. The tips and suggestions I share in this poster presentation have emerged as part of my own ongoing process to minimize student confusion, frustration, and improve engagement, while simultaneously impart greater agency and opportunity for success to the young adults populating my asynchronous online IAH courses here at MSU during the 2020-2021 academic year.

Background

In mid-March 2020, school pupils, university students, and educators everywhere were thrown into disarray by the mass onset of the Covid-19 virus, related lockdowns, and interruptions to normal student-instructor interactions.

At Michigan State University, we scrambled throughout the summer to prepare for the 2020-2021AY and reconfigure existing courses for online delivery.

Yet reasonably well developed and presented online courses alone have not enough for students to succeed. Even in the face of MSU’s push for empathy and understanding, students have demonstrated that they require additional help making the leap from traditional face-to-face to online learning.

Instructors are well-placed to assist students in an ongoing way as they make this challenging transition.

Without much additional work, we can support and encourage our students with weekly reminders that exhibit kind words, cues, prompts, signposts pointing the way forward, and calls to action.

We can foster improved student engagement, learning, and success despite the challenging, new environment in which we operate.

We can guide students through their many weekly activities with roadmaps to help them navigate course intricacies more easily

We can provide students with ample opportunity for new ways of learning, thinking, knowing, and the acquisition of 21st century skills.

In short, faculty teaching online courses occupy an ideal position to prepare students to operate more efficiently and productively in the real world after graduation since remote work and collaboration online is expected to increase markedly as society speeds further along into the 21st century.

Develop Supporting Communications

Beside online syllabi, course modules with seem to be clear directions, etc. students need reminders to keep an asynchronous online general education course in mind, on the rails, and moving forward.

Routine, consistent supporting communications to students from the instructor help to minimize student confusion.

Send reminders on the same day each week for the coming week.

Include headers in all course documents, and email signatures, listing a few ‘how to succeed in this course’ tips.

Share same supporting communication to weekly modules in LMS.

Students benefit from supporting communication that guide them through the activities for a given week during the semester.

When students see supporting communications routinely and predictably, they are more likely to remember and act on it.

Provide Weekly Guidelines

Through supporting communication, provide additional prompts, directions, clarifications, and reminders to students. Let’s call these weekly reminders “guidelines.”.

Emphasize steps students can take to achieve success in the course.

Keep guidelines fairly short and to the point to avoid information overload.

Include the week, your name, course name, and number at top of guidelines as both an advance organizer and to help guidelines standout in students’ email inboxes.

Provide students with concise ‘roadmaps’ in these guidelines making it easy to plan and carry out their coursework each week.

Conclude guidelines with a call to action for students to complete course-related activities, much like a TV or online commercial, or an old fashioned print ad.

Think of weekly guidelines as marketing communications that have a higher purpose than just promotion however.

Share same guidelines at top of weekly online modules in LMS, so students can access them in more than one place.

Include Key Course Policy Reminders

Students will not remember all course policies, and expectations outlined in our syllabi. Some might conveniently “forget.”

Provide gentle reminders from week to week.

Assist students by including important course information as part of the guidelines sent each week.

Remind students of key course policies, expectations, and their responsibilities as members of the course.

One possible segue way might be, “For students who have chosen to remain in this course, the expectation is. . .”

Remind students that we are in a university setting, they are adults, and to avoid letting themselves fall through the cracks.

Invite students to seek help or clarification from the instructor if they or their student learning team need it.

Foster Civil Interaction

We have asked students to make a huge leap into uncharted waters. They are frustrated and possibly fearful.

Many are not used to online learning, self-reflection, thinking on their feet, problem solving, or working cohesively with others.

Many already exhibit an entitled, customer service mindset.

Make expectations for civil interaction clear with a concise statement in online syllabi, modules, and weekly guidelines.

Model civility with polite decorum and kindness to reduce potential problems with disgruntled students.

Be respectful and civil in your synchronous, asynchronous, or email interaction with students. Listen without interrupting.

Avoid terse replies, even to naïve questions!

Use the student’s name in verbal or email replies.

Reduce the potential for unpleasant episodes by opening all email replies with “Thank you for your email,” and conclude them with “Best/Kind Regards. . .”

Be the adult in the room and show patience, patience, patience!

Here are vital teachable moments that allow us to help shape students for collegial and productive working lives following graduation.

Civil interaction is challenging given the various pressures and constraints under which all of us, faculty and students, must operate, but it is an important part of facilitating continued student engagement and success in our online courses.

Remind Students of the Skills They Cultivate

Besides the specific subject matter of the course, remind students in weekly guidelines that they are also cultivating real world expertise.

‘21st century skills, ’ a term used by Christopher J. Dede, John Richards and others in The 60-Year Curriculum: New Models for Lifelong Learning in the Digital Economy (2020), enable a smooth transition into the globalized digital economy after graduation.

Remind students that they are refining relevant skills in:

Deeper (critical) thinking

Collaboration and collegiality

Personal and agency and proactive engagement.

Effective planning and organization

Time management.

Intellectually openness and mental agility.

Learning from mistakes.

Accountability and ownership

Self-Awareness

Attention to detail

Timely and Frequent Communication with Your Team

Creative problem-solving

Development of high quality work

Consistency

On-time delivery of assignments and projects.

Self-regulation

Frequent practice of skills like these during weekly course-related activities better prepares students for long term employability through an anticipated six decades of working life in a rapidly changing world.

Establish Consistent Guideline Format

Below is a possible format for the weekly guidelines I propose:

A recurring header in your weekly that lists easy steps students can take to ensure their own success in course.

Begin with an advance organizer that identifies right away the week, semester, and dates the guidelines are for.

Follow with a friendly greeting and focusing statement in a brief paragraph.

Highlight any due dates in yellow below the greeting below greeting and focusing statement.

Include two-three concise paragraphs that enumerate and outline individual assignments or team projects for the week.

Provide brief directions for how (and when) to ask questions or seek clarification.

Furnish technical assistance contact information for students who experience challenges uploading assignments or team projects.

Remind students gently about the collaborative course design and expectations for students enrolled in the course.

Mention to students of the need to keep course policies and expectations in mind as they complete their work.

Highlight the big picture skills students practice each week besides the specific subject matter of the course, and how those skills are relevant to their lives after graduation.

Finish with a closing salutation that is a bit less formal and includes good wishes for students’ continued safety and well-being.

Conclusion

The approach outlined here has emerged, crystalized, and evolved over two semesters in the interest of ensuring student success in asynchronous online IAH courses.

While these observations are preliminary at this point, most students in the six courses taught during 2020-2021 have met the challenges facing them, completed their individual and collaborative coursework, and met or exceeded rubric expectations.

Anticipated student problems and drama either have not materialized, or have been minimal.

Early impressions suggest that supporting communications like these are helpful to students when it comes to navigating online courses more easily and completing related tasks.

Weekly supporting communications, presented as brief guidelines, might also be useful in the context in synchronous online, hybrid, and hy-flex as well as traditional face-to-face courses when it comes to helping students navigate and complete coursework in less confused, more systematic way.