We found 183 results that contain "interactive exercises"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Classroom Dynamics & Fostering Morale

As teachers or students, we each enter the classroom with expectations and norms that have been cultivated by the communities and cultures from which we come. As in many social spaces shared by people with diverse identities and backgrounds, it takes explicit effort to ensure that equity and inclusion are truly guiding principles for interactions in the classroom. These are important considerations for all educators; in your reflections and preparations for classroom instruction, interactions with graduate teaching assistants and advisees, and even in many engagments with other educators.CLASSROOM DYNAMICS

Be aware of power attached to social roles and power attached to social identities. Unequal power manifests in the classroom, for one, due to the differing social roles of instructor and student. Instructors exercise power in designing courses, leading class discussions or activities, deciding grades, and offering mentorship and connection to resources for student support and development.

Acknowledge and counter bias in the classroom. In the classroom, bias shows up implicitly and explicitly by way of course materials, classroom discussions, grading, evaluations, and more.When critically examining your course or classroom for bias, you may consider explicit and unacknowledge norms and expectations, financial burden of your course, representation in your syllabus (reading materials, cases, scenarios etc.), weight of class participation in grades, and other class policies.

Recognize and counter stereotype threat and lift. Stereotype threat is a phenomenon in which certain groups’ academic performance is negatively impacted due to increased vigilance about possibly confirming existing stereotypes. It's important to respect each of your students as individual learners and encourage a growth mindset in the classroom. This means normalizing mistakes and failures, emphasizing the value of challenge, and offering students a variety of ways to demonstrate their learning.

EARLY IN THE TERM

Introduce yourself to your class. Tell them about your background: how you first became interested in the subject, how it has been important to you, and why you are teaching this course. Genuinely convey your enthusiasm for the field and the subject; sharing your "why" for teaching in an authentic way. If you are comfortable doing so, introduce yourself so that your students know more than your name and contact information (e.g., outside interests, family, academic history, personal experiences). Centering yourself as a whole-human can set the tone for students doing the same.

Give students an opportunity to meet each other. Ask students to divide themselves into groups of three to five and introduce themselves. Or go around the room and ask all students to respond to one question, such as “What’s the one thing you really want to learn from this course?” or “What aspect of the course seems most appealing to you?”

Invite students to fill out an introduction card. Suggest that they indicate their name, year in school, major field of study, goals in the course, career plans, and so on.

Learn students’ names. By learning and using your students’ names, you can create a comfortable classroom environment that will encourage student interaction. Knowing your students’ names also tells them that you are interested in them as individuals. Did you know

Divide students into small groups. Give groups a small task, such as a brainstorming exercise, then place responses on the board for discussion and interpretation. These groups can change over time, regardless setting group agreements should be an established practice. CTLI has a student-facing survey library that includes a group agreement form. Learn more on accessing this library here.

Encourage students to actively support one another. Help them connect with at one or two other students in the class whom they can contact about missed classes, homework assignments, study groups and so on. You might also use the learning management system to create an online discussion forum where students can respond to each other's queries.

THROUGHOUT THE TERM

Let students know that they are not faces in an anonymous audience. In large courses, students often think that their classroom behaviour (eating, talking, sleeping, arriving late, etc.) goes unnoticed. Remind students that you and their classmates are aware of -- and affected by -- their behaviour.

If your class has extra seating space, ask students to refrain from sitting in certain rows of the classroom. For example, if you teach in a room that has rowed seating, ask students to sit in rows 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8 and so on so that you can walk through the audience where there is an empty row.

Recognize students’ extracurricular accomplishments. Read your campus newspaper, scan the dean’s list, pay attention to undergraduate awards and honours, and let students know that you are aware of their achievements.

Listen to students with warmth and respect. Give them your full attention. Be personable and approachable – remember the positive power of a smile.

Validate all comments and questions, even those that might seem irrelevant.

Welcome criticism and receive it with an open mind. Model for your students how you would like them to reflect on the feedback that you will be providing to them.

When you don’t know something, ask your students for help. For example, during class, ask someone with a laptop to do a Google search for a fact or piece of information that pertains to class discussion.

Be inclusive. Use gender-inclusive language and when giving examples make them culturally diverse.

Capitalize on outside events or situations, as appropriate. Relate major world events or events on campus both to your class and to the fabric of your students’ lives outside the classroom.

Arrive early and chat with students. Ask how the course is going. Are they enjoying the readings? Is there anything they want you to include in lectures?

Seek out students who are doing poorly in the course. Write “See me during my office hours” on all exams graded C- or below to provide individualized feedback.

Acknowledge students who are doing well in the course. Write “Good job! See me after class” on all exams graded A- or above. Take a moment after class to compliment students who are excelling.

Schedule topics for office hours. If students are reluctant to come, periodically schedule a “help session” on a particular topic rather than a free-form office hour.

Talk about questions students have asked in previous terms. Mention specific questions former students have asked and explain why they were excellent questions. This lets students know that you take their questions seriously and that their questions will contribute to the course in the future.

When feasible, give students a choice in the type of assignments they can do. For example, rather than assigning a traditional essay, give them the option of making a podcast, analysing a case study, giving a poster presentation, and so on.

Consider providing options for how the final grade will be calculated. For example, individual students can decide that the midterm will be worth 25% and a major project worth 35% -- or vice versa.

Listen attentively to all questions and answer them directly. If you will cover the answer during the remainder of the lecture, acknowledge the aptness of the question, ask the student to remember it, and answer the question directly when you arrive at that subject.

Try to empathize with beginners. Remember that not all of your students are as highly motivated and interested in the discipline as you were when you were a student. Slow down when explaining complex ideas, and acknowledge the difficulty and importance of certain concepts or operations. Try to recall your first encounter with a concept – what examples, strategies, or techniques clarified it for you?

When a student seems disgruntled with some aspect of the course, approach him or her in a supportive way and discuss the feelings, experiences, and perceptions that are contributing to the issue.

Celebrate student or class accomplishments. Instigate a round of applause, give congratulations, share cookies!

Thank you to colleagues in university educator development at the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning at Harvard University, the Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, and others for their materials that informed or were adapted into this resource.

Resources

Eble, K. E. (1988). The Craft of Teaching: A Guide to Mastering the Profession and Art. 2nd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Forsyth, D. R, & McMillan, J. H. (1991). Practical Proposals for Motivating Students. In Menges, R. J., & Svinicki, M. D., eds. College Teaching: From Theory to Practice. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, No.45. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, p.53-65.

Gross Davis, B. (2009). Tools for Teaching, 2nd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Ralph, E. G. (1998). Motivating Teaching in Higher Education: A Manual for Faculty Development. Stillwater, Oklahoma: New Forums Press, Inc.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (1978). Motivation and Teaching: A Practical Guide. Washington, D.C.: National Education Association.

Fostering Student Morale and Confidence. Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo

Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash

Be aware of power attached to social roles and power attached to social identities. Unequal power manifests in the classroom, for one, due to the differing social roles of instructor and student. Instructors exercise power in designing courses, leading class discussions or activities, deciding grades, and offering mentorship and connection to resources for student support and development.

Acknowledge and counter bias in the classroom. In the classroom, bias shows up implicitly and explicitly by way of course materials, classroom discussions, grading, evaluations, and more.When critically examining your course or classroom for bias, you may consider explicit and unacknowledge norms and expectations, financial burden of your course, representation in your syllabus (reading materials, cases, scenarios etc.), weight of class participation in grades, and other class policies.

Recognize and counter stereotype threat and lift. Stereotype threat is a phenomenon in which certain groups’ academic performance is negatively impacted due to increased vigilance about possibly confirming existing stereotypes. It's important to respect each of your students as individual learners and encourage a growth mindset in the classroom. This means normalizing mistakes and failures, emphasizing the value of challenge, and offering students a variety of ways to demonstrate their learning.

EARLY IN THE TERM

Introduce yourself to your class. Tell them about your background: how you first became interested in the subject, how it has been important to you, and why you are teaching this course. Genuinely convey your enthusiasm for the field and the subject; sharing your "why" for teaching in an authentic way. If you are comfortable doing so, introduce yourself so that your students know more than your name and contact information (e.g., outside interests, family, academic history, personal experiences). Centering yourself as a whole-human can set the tone for students doing the same.

Give students an opportunity to meet each other. Ask students to divide themselves into groups of three to five and introduce themselves. Or go around the room and ask all students to respond to one question, such as “What’s the one thing you really want to learn from this course?” or “What aspect of the course seems most appealing to you?”

Invite students to fill out an introduction card. Suggest that they indicate their name, year in school, major field of study, goals in the course, career plans, and so on.

Learn students’ names. By learning and using your students’ names, you can create a comfortable classroom environment that will encourage student interaction. Knowing your students’ names also tells them that you are interested in them as individuals. Did you know

Divide students into small groups. Give groups a small task, such as a brainstorming exercise, then place responses on the board for discussion and interpretation. These groups can change over time, regardless setting group agreements should be an established practice. CTLI has a student-facing survey library that includes a group agreement form. Learn more on accessing this library here.

Encourage students to actively support one another. Help them connect with at one or two other students in the class whom they can contact about missed classes, homework assignments, study groups and so on. You might also use the learning management system to create an online discussion forum where students can respond to each other's queries.

THROUGHOUT THE TERM

Let students know that they are not faces in an anonymous audience. In large courses, students often think that their classroom behaviour (eating, talking, sleeping, arriving late, etc.) goes unnoticed. Remind students that you and their classmates are aware of -- and affected by -- their behaviour.

If your class has extra seating space, ask students to refrain from sitting in certain rows of the classroom. For example, if you teach in a room that has rowed seating, ask students to sit in rows 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8 and so on so that you can walk through the audience where there is an empty row.

Recognize students’ extracurricular accomplishments. Read your campus newspaper, scan the dean’s list, pay attention to undergraduate awards and honours, and let students know that you are aware of their achievements.

Listen to students with warmth and respect. Give them your full attention. Be personable and approachable – remember the positive power of a smile.

Validate all comments and questions, even those that might seem irrelevant.

Welcome criticism and receive it with an open mind. Model for your students how you would like them to reflect on the feedback that you will be providing to them.

When you don’t know something, ask your students for help. For example, during class, ask someone with a laptop to do a Google search for a fact or piece of information that pertains to class discussion.

Be inclusive. Use gender-inclusive language and when giving examples make them culturally diverse.

Capitalize on outside events or situations, as appropriate. Relate major world events or events on campus both to your class and to the fabric of your students’ lives outside the classroom.

Arrive early and chat with students. Ask how the course is going. Are they enjoying the readings? Is there anything they want you to include in lectures?

Seek out students who are doing poorly in the course. Write “See me during my office hours” on all exams graded C- or below to provide individualized feedback.

Acknowledge students who are doing well in the course. Write “Good job! See me after class” on all exams graded A- or above. Take a moment after class to compliment students who are excelling.

Schedule topics for office hours. If students are reluctant to come, periodically schedule a “help session” on a particular topic rather than a free-form office hour.

Talk about questions students have asked in previous terms. Mention specific questions former students have asked and explain why they were excellent questions. This lets students know that you take their questions seriously and that their questions will contribute to the course in the future.

When feasible, give students a choice in the type of assignments they can do. For example, rather than assigning a traditional essay, give them the option of making a podcast, analysing a case study, giving a poster presentation, and so on.

Consider providing options for how the final grade will be calculated. For example, individual students can decide that the midterm will be worth 25% and a major project worth 35% -- or vice versa.

Listen attentively to all questions and answer them directly. If you will cover the answer during the remainder of the lecture, acknowledge the aptness of the question, ask the student to remember it, and answer the question directly when you arrive at that subject.

Try to empathize with beginners. Remember that not all of your students are as highly motivated and interested in the discipline as you were when you were a student. Slow down when explaining complex ideas, and acknowledge the difficulty and importance of certain concepts or operations. Try to recall your first encounter with a concept – what examples, strategies, or techniques clarified it for you?

When a student seems disgruntled with some aspect of the course, approach him or her in a supportive way and discuss the feelings, experiences, and perceptions that are contributing to the issue.

Celebrate student or class accomplishments. Instigate a round of applause, give congratulations, share cookies!

Thank you to colleagues in university educator development at the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning at Harvard University, the Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, and others for their materials that informed or were adapted into this resource.

Resources

Eble, K. E. (1988). The Craft of Teaching: A Guide to Mastering the Profession and Art. 2nd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Forsyth, D. R, & McMillan, J. H. (1991). Practical Proposals for Motivating Students. In Menges, R. J., & Svinicki, M. D., eds. College Teaching: From Theory to Practice. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, No.45. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, p.53-65.

Gross Davis, B. (2009). Tools for Teaching, 2nd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Ralph, E. G. (1998). Motivating Teaching in Higher Education: A Manual for Faculty Development. Stillwater, Oklahoma: New Forums Press, Inc.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (1978). Motivation and Teaching: A Practical Guide. Washington, D.C.: National Education Association.

Fostering Student Morale and Confidence. Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo

Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Classroom Dynamics & Fostering Morale

As teachers or students, we each enter the classroom with expectati...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Tuesday, Oct 17, 2023

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Break-out rooms? There's an app for that.

Zoom break-out rooms are a go-to option for student-student interaction in online courses. When I think about break-out rooms, the image I see commonly displays a blue 'Share' button in the upper right, this is how accustomed I have become to seeing Google Apps along with Zoom. Works great, facilitates interaction, leaves an artefact that can be used to assess understanding. As time went by, we got better at it. Instead of hearing 'I forgot what group I was in', groups would have names. We even used 'come up with a group name' as a get-to-know each other activity. We learned that having a single document shared by all worked for some situations, but we could also make group folders for holding supporting documents and individualized instructions. We could control access or have students share from their own Google Drives.

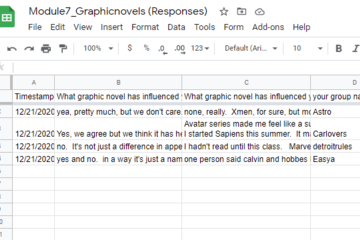

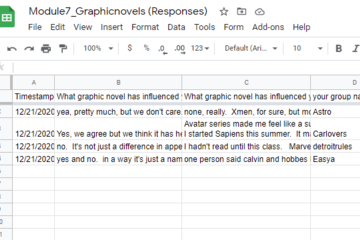

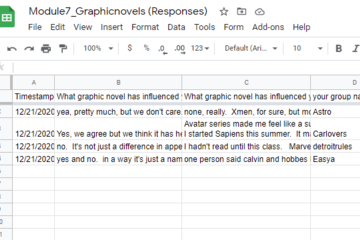

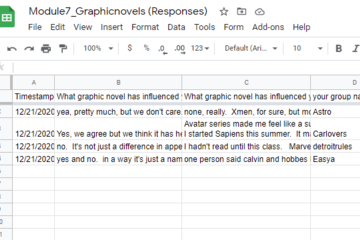

My next break-through for break-outs: Google Forms. So glad I saw that demonstrated. The report-out instructions could be right in the form, and could include images and video. Forms could be copied or questions imported, thus saving time. And responses all went neatly into columns and rows on a Sheet, which could be converted to a Doc if we that made reviewing easier.

I only recently opened the door into the big candy shop of Google App joy, and it wasn't for work. My child is taking piano lessons online. In person, the teacher would annotate his book to adjust a phrase for exercise purposes or to transpose the key. Online, the teacher was relying on my son to record the changes. That didn't happen. But the boy had a suggestion for the teacher: use a Google doc with musical notation. This was new to us, but sure enough, in the Chrome Web Store we found an add-on called 'Flat'. (Not a very enticing name, but 'Sharp' is taken.) Flat is a blast and fun way to learn. In addition to musical notation, it can make guitar and ukulele tabs so we can quickly try the music on other instruments, and we can have a group play together. While I was in the Store, I also grabbed an add-on called MathType, which we could use for math and chemistry but for some reason we just haven't got to that.

Something else that is cool: Microsoft Edge accepts Chrome add-ons, because both browsers are built in Chromium. I don't want to give up Edge: I love being able to search the MSU cloud from my browser. If you haven't tried that, just use Bing in Edge, and check out the results under the 'WORK' heading. It will even take you to your Teams chats. Amazing.

My next break-through for break-outs: Google Forms. So glad I saw that demonstrated. The report-out instructions could be right in the form, and could include images and video. Forms could be copied or questions imported, thus saving time. And responses all went neatly into columns and rows on a Sheet, which could be converted to a Doc if we that made reviewing easier.

I only recently opened the door into the big candy shop of Google App joy, and it wasn't for work. My child is taking piano lessons online. In person, the teacher would annotate his book to adjust a phrase for exercise purposes or to transpose the key. Online, the teacher was relying on my son to record the changes. That didn't happen. But the boy had a suggestion for the teacher: use a Google doc with musical notation. This was new to us, but sure enough, in the Chrome Web Store we found an add-on called 'Flat'. (Not a very enticing name, but 'Sharp' is taken.) Flat is a blast and fun way to learn. In addition to musical notation, it can make guitar and ukulele tabs so we can quickly try the music on other instruments, and we can have a group play together. While I was in the Store, I also grabbed an add-on called MathType, which we could use for math and chemistry but for some reason we just haven't got to that.

Something else that is cool: Microsoft Edge accepts Chrome add-ons, because both browsers are built in Chromium. I don't want to give up Edge: I love being able to search the MSU cloud from my browser. If you haven't tried that, just use Bing in Edge, and check out the results under the 'WORK' heading. It will even take you to your Teams chats. Amazing.

Authored by:

David Howe

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Break-out rooms? There's an app for that.

Zoom break-out rooms are a go-to option for student-student interac...

Authored by:

Saturday, Jan 16, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Instructional Guidance Is Key to Promoting Active Learning in Online and Blended Courses

Instructional Guidance Is Key to Promoting Active Learning in Online and Blended Courses Written by: Jay Loftus Ed.D. (MSU / CTLI) & Michele Jacobsen, Ph.D. (Werklund School of Education - University of Calgary)

Abstract - Active learning strategies tend to originate from one of two dominant philosophical perspectives. The first position is active learning as an instructional philosophy, whereby inquiry-based and discovery learning are primary modalities for acquiring new information. The second perspective considers active learning a strategy to supplement the use of more structured forms of instruction, such as direct instruction. From the latter perspective, active learning is employed to reinforce conceptual learning following the presentation of factual or foundational knowledge. This review focuses on the second perspective and uses of active learning as a strategy. We highlight the need and often overlooked requirement for including instructional guidance to ensure active learning, which can be effective and efficient for learning and learners.

Keywords - Active learning, instructional guidance, design strategy, cognitive load, efficiency, online and blended courses

Introduction

Learner engagement in online courses has been a central theme in educational research for several years (Martin, Sun and Westing, 2020). As we consider the academic experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2020 and started to subside in 2022, it is essential to reflect on the importance of course quality (Cavanaugh, Jacquemin and Junker, 2023) and learner experience in online courses (Gherghel, Yasuda and Kita, 2023). Rebounding from our collected experience, learner engagement continues to be an important element of course design and delivery. This fact was highlighted in 2021, when the United States Department of Education (DOE) set forth new standards for institutions offering online courses. To be eligible for Title IV funding, new standards require non-correspondence courses to ensure regular and substantive interactions (RSI) between instructors and students (Downs, 2021). This requirement necessitates the need to find ways to engage students allowing instructors the ability to maximize their interactions. One possible solution is to use active learning techniques that have been shown to increase student engagement and learning outcomes (Ashiabi & O’ Neal, 2008; Cavanaugh et al., 2023).

Active learning is an important instructional strategy and pedagogical philosophy used to design quality learning experiences and foster engaging and interactive learning environments. However, this is not a novel perspective. Many years ago in their seminal work, Chickering and Gamson (1987) discussed the issue of interaction between instructors and students, suggesting that this was an essential practice for quality undergraduate education. The newfound focus on active learning strategies has become more pronounced following an examination of instructional practices from 2020 to 2022. For example, Tan, Chng, Chonardo, Ng and Fung (2020) examined how chemistry instructors incorporated active learning into their instruction to achieve equivalent learning experiences in pre-pandemic classrooms. Similarly, Misra and Mazelfi (2021) described the need to incorporate group work or active learning activities into remote courses to: ‘increase students’ learning motivation, enforce mutual respect for friends’ opinions, foster excitement’ (p. 228). Rincon-Flores & Santos-Guevara (2021) found that gamification as a form of active learning, ‘helped to motivate students to participate actively and improved their academic performance, in a setting where the mode of instruction was remote, synchronous, and online’ (p.43). Further, the implementation of active learning, particularly gamification, was found to be helpful for promoting a more humanizing learning experience (Rincon-Flores & Santos-Guevara, 2021).

This review examines the use of active learning and presents instructional guidance as an often-overlooked element that must be included to make active learning useful and effective. The omission of explicit and direct instructional guidance when using active learning can be inefficient, resulting in an extraneous cognitive burden on learners (Lange, Gorbunova, Shcheglova and Costley, 2022). We hope to outline our justification through a review of active learning and offer strategies to ensure that the implementation of active learning is effective.

Active Learning as an Instructional Philosophy

Active learning is inherently a ‘student-centered’ instructional paradigm that is derived from a constructivist epistemological perspective (Krahenbuhl, 2016; Schunk, 2012). Constructivism theorizes that individuals construct their understanding through interactions and engagements, whereby the refinement of skills and knowledge results over time (Cobb & Bowers, 1999). Through inquiry, students produce experiences and make connections that lead to logical and conceptual growth (Bada & Olusegun, 2015). Engaging learners in activities, tasks, and planned experiences is an overarching premise of active learning as an instructional philosophy. As an overarching instructional philosophy, the role of instructional guidance can be minimized. As Hammer (1997) pointed out many years ago, the role of the instructor in these environments is to provide content and materials, and students are left make ‘discoveries’ through inquiry.

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is an instructional practice that falls under the general category of ‘active learning’. The tenets of IBL adhere to a constructivist learning philosophy (de Jong et al., 2023) and can be characterized by the following six elements (Duncan & Chinn, 2021). Students will:

Generate knowledge through investigation of a novel issue or problem.

Work ‘actively’ to discover new findings.

Use of evidence to derive conclusions.

Take responsibility for their own learning through ‘epistemological agency’ (Chinn & Iordanou, 2023) and share their learning with a community of learners.

Use problem-solving and reasoning for complex tasks.

Collaborate, share ideas, and derive solutions with peers.

Historically, inquiry-based learning as a form of active learning was adopted as an overall instructional paradigm in disciplines such as medicine and was closely aligned with problem-based learning (PBL) (Barrows, 1996). Proponents of PBL advocate its use because of its emphasis on the development of skills such as communication, collaboration, and critical thinking (Dring, 2019). Critics of these constructivist approaches to instruction highlight the absence of a structure and any form of instructional guidance (Zhang & Cobern, 2021). Instead, they advocate a more explicit form of instruction such as direct instruction (Zhang, Kirschner, Corben and Sweller, 2022).

The view that a hybrid of IBL coupled with direct instruction is the optimal approach to implementing active learning has been highlighted in the recent academic literature (de Jong et al., 2023). The authors suggest that the selection of direct instruction or active learning strategies, such as IBL, should be guided by the desired outcomes of instruction. If the goal of instruction is the acquisition of more foundational or factual information, direct instruction is the preferred strategy. Conversely, IBL strategies are more appropriate ‘for the promotion of deep understanding and transferrable conceptual understanding of topics that are open-ended or susceptible to misconceptions’ (de Jong et al., 2023 p. 7).

The recommendation to use both direct instruction and approaches like IBL has reframed active learning as an instructional strategy rather than an overarching pedagogical philosophy. Active learning should be viewed as a technique or strategy coupled with direct instructional approaches (de Jong et al., 2023).

Active Learning as an Instructional Strategy

Approaching active learning as an instructional strategy rather than an overarching instructional philosophy helps clarify and address the varying perspectives found in the literature. Zhang et al. (2022) suggested that there is a push to emphasize exploration-based pedagogy. This includes instructional approaches deemed to be predicated on inquiry, discovery, or problem-based approaches. This emphasis has resulted in changes to curricular policies that mandate the incorporation of these instructional philosophies. Zhang et al. (2022) discussed how active learning approaches can be incorporated into science education policy to emphasize ‘inquiry’ approaches, despite adequate evidence for effectiveness. Zhang et al. (2022) stated that the ‘disjoint between policy documents and research evidence is exacerbated by the tendency to ignore categories of research that do not provide the favored research outcomes that support teaching science through inquiry and investigations’ (p. 1162). Instead, Zhang et al. (2022) advocate for direct instruction as the primary mode of instruction in science education with active learning or ‘inquiry’ learning incorporated as a strategy, arguing that conceptual or foundational understanding ‘should not be ‘traded off’ by prioritizing other learning outcomes’ (p. 1172).

In response to Zhang et al. ’s (2022) critique, de Jong et al. (2023) argued that research evidence supports the use of inquiry-based instruction for the acquisition of conceptual understanding in science education. They asserted that both inquiry-based (or active learning approaches) and direct instruction serve specific learning needs. Direct instruction may be superior for foundational or factual learning, while inquiry-based or active learning may be better for conceptual understanding and reinforcement. The conclusion of de Jong et al. ’s (2023) argument suggests the use of a hybrid of direct instruction and active learning techniques, such as inquiry-based designs, depending on the stated learning objectives of the course or the desired outcomes.

This hybrid approach to instructional practice can help ensure that intended learning outcomes are matched with effective instructional strategies. Furthermore, a hybrid approach can help maintain efficiency in learning rather than leaving the acquisition of stated learning outcomes to discovery or happenstance (Slocum & Rolf, 2021). This notion was supported by Nerantzi's (2020) suggestion that ‘students learn best when they are active and immersed in the learning process, when their curiosity is stimulated, when they can ask questions and debate in and outside the classroom, when they are supported in this process and feel part of a learning community’ (p. 187). Emphasis on learner engagement may support the belief that active learning strategies combined with direct instruction may provide an optimal environment for learning. Active learning strategies can be used to reinforce the direct or explicit presentation of concepts and principles (Lapitan Jr, Tiangco, Sumalinog, Sabarillo and Diaz, 2021).

Recently, Zhang (2022) examined the importance of integrating direct instruction with hands-on investigation as an instructional model in high school physics classes. Zhang (2022) determined that ‘students benefit more when they develop a thorough theoretical foundation about science ideas before hands-on investigations’ (p. 111). This supports the earlier research in post-secondary STEM disciplines as reported by Freeman, Eddy, McDonough and Wenderoth (2014), where the authors suggested that active learning strategies help to improve student performance. The authors further predicted that active learning interventions would show more significant learning gains when combined with ‘required exercises that are completed outside of formal class sessions’ (p. 8413).

Active Learning Strategies

Active learning is characterized by activities, tasks, and learner interactions. Several characteristics of active learning have been identified, including interaction, peer learning, and instructor presence (Nerantzi, 2020). Technology affords students learning opportunities to connect pre-, during-, and post-formal learning sessions (Zou & Xie, 2019; Nerantzi, 2020). The interactions or techniques that instructors use help determine the types of interactions and outcomes that will result. Instructors may be ‘present’ or active in the process but may not provide adequate instructional guidance for techniques to be efficient or effective (Cooper, Schinske and Tanner, 2021; Kalyuga, Chandler and Sweller. 2001). To highlight this gap, we first consider the widely used technique of think-pair-share, an active learning strategy first introduced by Lyman (1981). This active learning strategy was introduced to provide all students equitable opportunities to think and discuss ideas with their peers. The steps involved in this technique were recently summarized (Cooper et al., 2021): i) provide a prompt or question to students, (ii) give students a chance to think about the question or prompt independently, (iii) have students share their initial answers/responses with a neighbor in a pair or a small group, and (iv) invite a few groups a chance to share their responses with the whole class.

Instructional guidance outlines the structure and actions associated with a task. This includes identifying the goals and subgoals, and suggesting strategies or algorithms to complete the task (Kalyuga et al., 2001). Employing the strategy of think-pair-sharing requires more instructional guidance than instructors may consider. The title of the strategy foreshadows what students will ‘do’ to complete the activity. However, instructional guidance is essential to help students focus on the outcome, rather than merely enacting the process of the activity. Furthermore, instructional guidance or instructions given to students when employing think-pair-sharing can help make this activity more equitable. Cooper et al. (2021) point out that equity is an important consideration when employing think-pair-share. Often, think-pair-share activities are not equitable during the pair or share portion of the exercise, and can be dominated by more vocal or boisterous students. Instructional guidance can help ensure that the activity is more equitable by providing more explicit instructions on expectations for sharing. For example, the instructions for a think-pair-share activity may include those that require each student to compose and then share ideas on a digital whiteboard or on a slide within a larger shared slide deck. The opportunity for equitable learning must be built into the instructions given to students. Otherwise, the learning experience could be meaningless or lack the contribution of students who are timid or find comfort in a passive role during group learning.

Further considerations for instructional guidance are necessary since we now use various forms of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) to promote active learning strategies. Web conferencing tools, such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet, were used frequently during the height of required remote or hybrid teaching (Ahshan, 2021). Activities that separated students into smaller work groups via breakout rooms or unique discussion threads often included instructions on what students were to accomplish in these smaller collaborative groups. However, the communication of expectations or explicit guidance to help direct students in these groups were often not explicit or were not accessible once the students had been arranged into their isolated workspaces. These active learning exercises would have benefited from clear guidance and instructions on how to ‘call for help’ once separated from the larger group meetings. For example, Li, Xu, He, He, Pribesh, Watson and Major, (2021) described an activity for pair programming that uses zoom breakout rooms. In their description, the authors outlined the steps learners were expected to follow to successfully complete the active learning activity, as well as the mechanisms students used to ask for assistance once isolated from the larger Zoom session that contained the entire class. The description by Li et al. (2021) provided an effective approach to instructional guidance for active learning using Zoom. Often, instructions are verbalized or difficult to refer to once individuals are removed from the general or common room. The lack of explicit instructional guidance in these activities can result in inefficiency (Kalyuga et al., 2001) and often inequity (Cooper et al., 2021).

The final active learning approach considered here was a case study analysis of asynchronous discussion forums. To extend engagement with course content, students were assigned a case study to discuss in a group discussion forum. The group is invited to apply course concepts and respond to questions as they analyze the case and prepare recommendations and a solution (Hartwell et al., 2021). Findings indicate that case study analysis in discussion forums as an active learning strategy “encouraged collaborative learning and contributed to improvement in cognitive learning” (Seethamraju, 2014, p. 9). While this active learning strategy can engage students with course materials to apply these concepts in new situations, it can also result in a high-volume-low-yield set of responses and posts without sufficient instructional guidance and clear expectations for engagement and deliverables. Hartwell, Anderson, Hanlon, and Brown (2021) offer guidance on the effective use of online discussion forums for case study analysis, such as clear expectations for student work in teams (e.g., a team contract), ongoing teamwork support through regular check-ins and assessment criteria, clear timelines and tasks for individual analysis, combined group discussion and cross-case comparison, review of posted solutions, and requirements for clear connections between case analysis and course concepts.

Active Learning & Cognitive Load Theory

In a recent review of current policy and educational standards within STEM disciplines, Zhang et al. (2022) argued that structured instructional approaches such as direct instruction align more closely with cognitive-based learning theories. These theories are better at predicting learning gains and identifying how learning occurs. Cognitive load theory is one such theory based on three main assumptions. First, humans have the capacity to obtain novel information through problem-solving or from other people. Obtaining information from other individuals is more efficient than generating solutions themselves. Second, acquired information is confronted by an individual’s limited capacity to first store information in working memory and then transfer it to unlimited long-term memory for later use. Problem-solving imposes a heavy burden on limited working memory. Thus, learners often rely on the information obtained from others. Finally, information stored in long-term memory can be transferred back to working memory to deal with familiar situations (Sweller, 2020). The recall of information from long-term memory to working memory is not bound by the limits of the initial acquisition of information in working memory (Zhang et al., 2022).

Zhang et al. (2022) state that ‘there never is a justification for engaging in inquiry-based learning or any other pedagogically identical approaches when students need to acquire complex, novel information’ (p. 1170). This is clearly a one-sided argument that focuses on the acquisition of information rather than the application of acquired information. This also presents an obvious issue related to the efficiency of acquiring novel information. However, Zhang et al. (2022) did not argue against the use of active learning or inquiry learning strategies to help reinforce concepts, or the use of the same to support direct instruction.

The combination of active learning strategies with direct instruction can be modified using assumptions of cognitive load, which highlights the need to include instructional guidance with active learning strategies. The inclusion of clear and precise instructions or instructional guidance is critical for effective active learning strategies (Murphy, 2023). As de Jong et al. (2023) suggest, ‘guidance is (initially) needed to make inquiry learning successful' (p.9). We cannot assume that instructional guidance is implied through the name of the activity or can be determined from the previous learning experiences of students. Assumptions lead to ambiguous learning environments that lack instructional guidance, force learners to infer expectations, and rely on prior and/or potentially limited active learning experiences. In the following section, we offer suggestions for improving the use of active learning strategies in online and blended learning environments by adding instructional guidance.

Suggestions for Improving the Use of Active Learning in Online and Blended Courses

The successful implementation of active learning depends on several factors. One of the most critical barriers to the adoption of active learning is student participation. As Finelli et al. (2018) highlighted, students may be reluctant to participate demonstrating behaviors such as, ‘not participating when asked to engage in an in-class activity, distracting other students, performing the required task with minimal effort, complaining, or giving lower course evaluations’ (p. 81). These behaviors are reminiscent of petulant adolescents, often discouraging instructors from implementing active learning in the future. To overcome this, the authors suggested that providing a clear explanation of the purpose of the active learning exercise would help curb resistance to participation. More recently, de Jong et al. (2023) stated a similar perspective that ‘a key issue in interpreting the impact of inquiry-based instruction is the role of guidance’ (p. 5). The inclusion of clear and explicit steps for completing an active learning exercise is a necessary design strategy. This aspect of instructional guidance is relatively easy to achieve with the arrival of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools used to support instructors. As Crompton and Burke (2024) pointed out in their recent review, ‘ChatGPT can assist teachers in the creation of content, lesson plans, and learning activities’ (p.384). More specifically, Crompton and Burke (2024) suggested that generative AI could be used to provide step-by-step instructions for students. To illustrate this point, we entered the following prompt into the generative AI tool, goblin.tools (https://goblin.tools/) ‘Provide instructions given to students for a carousel activity in a college class.’ The output is shown in Fig. 1. This tool is used to break down tasks into steps, and if needed, it can further break down each step into a more discrete sequence of steps.

Figure 1 . Goblin.tools instructions for carousel active learning exercises.

The omission of explicit steps or direct instructional guidance in an active learning exercise can potentially increase extraneous cognitive load (Klepsch & Seufert, 2020; Sweller, 2020). This pernicious impact on cognitive load is the result of the diversion of one’s limited capacity to reconcile problems (Zhang, 2022). Furthermore, the complexity of active learning within an online or blended course is exacerbated by the inclusion of technologies used for instructional purposes. Instructional guidance should include requisite guidance for tools used in active learning. Again, generative AI tools, such as goblin.tools, may help mitigate the potential burden on cognitive load. For example, the use of webconferencing tools, such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams, has been pervasive in higher education. Anyone who uses these tools can relate to situations in which larger groups are segmented into smaller groups in isolated breakout rooms. Once participant relocation has occurred, there is often confusion regarding the intended purpose or goals of the breakout room. Newer features, such as collaborative whiteboards, exacerbate confusion and the potential for excessive extraneous load. Generative AI instructions (see Figure 2) could be created and offered to mitigate confusion and cognitive load burden.

Figure 2. Zoom collaborative whiteboard instructions produced by goblin.tools

Generative AI has the potential to help outline the steps in active learning exercises. This can be used to minimize confusion and serve as a reference for students. However, instruction alone is often insufficient to make active learning effective. As Finelli et al. (2018) suggest, the inclusion of a rationale for implementing active learning is an effective mechanism to encourage student participation. To this end, we suggest the adoption of what Bereiter (2014) called Principled Practical Knowledge (PPK) which consists of the combination of ‘know-how’ with ‘know why’ (Bereiter, 2014). This perspective develops out of learners’ efforts to solve practical problems. It is a combination of knowledge that extends beyond simply addressing the task at hand. There is an investment of effort to provide a rationale or justification to address the ‘know why’ portion of PPK (Bereiter, 2014). Creating conditions for learners to develop ‘know-how’ is critical when incorporating active learning strategies in online and blended courses. Instructional guidance can reduce ambiguity and extraneous load and can also increase efficiency and potentially equity.

What is typically not included in the instructional guidance offered to students is comprehensive knowledge that outlines the requirements for technology that is often employed in active learning strategies. Ahshan (2021) suggests that technology skill competency is essential for the instructors and learners to implement the activities smoothly. Therefore, knowledge should include the tools employed in active learning. Instructors cannot assume that learners have a universal baseline of technological competency and thus need to be aware of this diversity when providing instructional guidance.

An often-overlooked element of instructional guidance connected to PPK is the ‘know-why’ component. Learners are often prescribed learning tasks without a rationale or justification for their utility. The underlying assumption for implementing active learning strategies is the benefits of collaboration, communication, and collective problem-solving are clear to learners (Dring, 2019; Hartikainen et al., 2019). However, these perceived benefits or rationales are often not provided explicitly to learners; instead, they are implied through use.

When implementing active learning techniques or strategies in a blended or online course one needs to consider not only the ‘know-how,’ but also the ‘know-why.’ Table 1 helps to identify the scope of instructional guidance that should be provided to students.

Table 1. Recommended Type of Instructional Guidance for Active Learning

Know How

Know Why

Activity

Steps

Purpose / Rationale

Technology

Steps

Purpose / Rationale

Outcomes / Products

Completion

Goals

The purpose of providing clear and explicit instructional guidance to learners is to ensure efficiency, equity, and value in incorporating active learning strategies into online and blended learning environments. Along with our argument for “know-why” (Bereiter, 2012), we draw upon Murphy (2023) who highlights the importance of “know-how’ by stating, ‘if students do not understand how a particular learning design helps them arrive at a particular outcome, they tend to be less invested in a course’ (n.p.).

Clear instructional guidance does not diminish the authenticity of various active learning strategies such as problem-based or inquiry-based techniques. In contrast, guidance serves to scaffold the activity and clearly outline learner expectations. Design standards organizations, such as Quality Matters, suggest the inclusion of statements that indicate a plan for how instructors will engage with learners, as well as the requirements for learner engagement in active learning. These statements regarding instructor engagement could be extended to include more transparency in the selection of instructional strategies. Murphy (2023) suggested that instructors should ‘pull back the curtain’ and take a few minutes to share the rationale and research that informs their decision to use strategies such as active learning. Opening a dialogue about the design process with students helps to manage expectations and anxieties that students might have in relation to the ‘What?’, ‘Why?’ and ‘How?’ for the active learning exercises.

Implications for Future Research

We contend that a blend of direct instruction and active learning strategies is optimized by instructional guidance, which provides explicit know-how and know-why for students to engage in learning tasks and activities. The present discussion does not intend to evaluate the utility of active learning as an instructional strategy. The efficacy of active learning is a recurring theme in the academic literature, and the justification for efficacy is largely anecdotal or based on self-reporting data from students (Hartikainen, Rintala, Pylväs and Nokelainen, 2019). Regardless, the process of incorporating active learning strategies with direct instruction appears to be beneficial for learning (Ahshan, 2021; Christie & De Graaff, 2017; Mintzes, 2020), and more likely, the learning experience can be harder to quantify. Our argument relates to the necessary inclusion of instructions and guidance that make the goals of active learning more efficient and effective (de Jong et al., 2023). Scardamalia and Bereiter (2006) stated earlier that knowledge about dominates traditional educational practice. It is the stuff of textbooks, curriculum guidelines, subject-matter tests, and typical school “projects” and “research” papers. Knowledge would be the product of active learning. In contrast, knowledge of, ‘suffers massive neglect’ (p. 101). Knowledge enables learners to do something and allows them to actively participate in an activity. Knowledge comprises both procedural and declarative knowledge. It is activated when the need for it is encountered in the action. Instructional guidance can help facilitate knowledge of, making the use of active learning techniques more efficient and effective.

Research is needed on the impact of instructional guidance on active learning strategies, especially when considering the incorporation of more sophisticated technologies and authentic problems (Rapanta, Botturi, Goodyear, Guardia and Koole 2021; Varvara, Bernardi, Bianchi, Sinjari and Piattelli, 2021). Recently, Lee (2020) examined the impact of instructor engagement on learning outcomes in an online course and determined that increased instructor engagement correlated with enhanced discussion board posts and student performance. A similar examination of the relationship between the instructional guidance provided and student learning outcomes would be a valuable next step. It could offer more explicit guidance and recommendations for the design and use of active learning strategies in online or blended courses.

Conclusion

Education was disrupted out of necessity for at least two years. This experience forced us to examine our practices in online and blended learning, as our sample size for evaluation grew dramatically. The outcome of our analysis is that effective design and inclusion of student engagement and interactions with instructors are critical for quality learning experiences (Rapanta et al., 2021; Sutarto, Sari and Fathurrochman, 2020; Varvara et al., 2021). Active learning appeals to many students (Christie & De Graaff, 2017) and instructors as it can help achieve many of the desired and required outcomes of our courses and programs. Our review and discussion highlighted the need to provide clear and explicit guidance to help minimize cognitive load and guide students through an invaluable learning experience. Further, instructors and designers who include explicit guidance participate in a metacognitive process, while they outline the purpose and sequence of steps required for the completion of active learning exercises. Creating instructions and providing a rationale for the use of active learning in a course gives instructors and designers an opportunity to reflect on the process and ensure that it aligns with the intended purpose or stated goals of the course. This reflective act makes active learning more intentional in use rather than employing it to ensure that students are present within the learning space.

References

Ahshan, R. (2021). A Framework of Implementing Strategies for Active Student Engagement in Remote/Online Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education Sciences, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090483

Ashiabi, G. S., & O’neal, K. K. (2008). A Framework for Understanding the Association Between Food Insecurity and Children’s Developmental Outcomes. Child Development Perspectives, 2(2), 71–77.

Bada, S. O., & Olusegun, S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66–70.

Barrows, H. S. (1996). Problem‐based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1996(68), 3–12.

Bereiter, C. (2014). Principled practical knowledge: Not a bridge but a ladder. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(1), 4–17.

Cavanaugh, J., Jacquemin, S. J., & Junker, C. R. (2023). Variation in student perceptions of higher education course quality and difficulty as a result of widespread implementation of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(4), 1787–1802.

Chinn, C. A., & Iordanou, K. (2023). Theories of Learning. Handbook of Research on Science Education: Volume III.

Christie, M., & De Graaff, E. (2017). The philosophical and pedagogical underpinnings of Active Learning in Engineering Education. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42(1), 5–16.

Cobb, P., & Bowers, J. (1999). Cognitive and situated learning perspectives in theory and practice. Educational Researcher, 28(2), 4–15.

Cooper, K. M., Schinske, J. N., & Tanner, K. D. (2021). Reconsidering the share of a think–pair–share: Emerging limitations, alternatives, and opportunities for research. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 20(1), fe1.

Crompton, H., & Burke, D. (2024). The Educational Affordances and Challenges of ChatGPT: State of the Field. TechTrends, 1–13.

de Jong, T., Lazonder, A. W., Chinn, C. A., Fischer, F., Gobert, J., Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Koedinger, K. R., Krajcik, J. S., Kyza, E. A., & Linn, M. C. (2023). Let’s talk evidence–The case for combining inquiry-based and direct instruction. Educational Research Review, 100536.

Dring, J. C. (2019). Problem-Based Learning – Experiencing and understanding the prominence during Medical School: Perspective. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 47, 27–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2019.09.004

Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2021). International handbook of inquiry and learning. Routledge.

Finelli, C. J., Nguyen, K., DeMonbrun, M., Borrego, M., Prince, M., Husman, J., Henderson, C., Shekhar, P., & Waters, C. K. (2018). Reducing student resistance to active learning: Strategies for instructors. Journal of College Science Teaching, 47(5).

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415.

Hammer, D. (1997). Discovery learning and discovery teaching. Cognition and Instruction, 15(4), 485–529.

Hartikainen, S., Rintala, H., Pylväs, L., & Nokelainen, P. (2019). The Concept of Active Learning and the Measurement of Learning Outcomes: A Review of Research in Engineering Higher Education. Education Sciences, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040276

Hartwell, A., Anderson, M., Hanlon, P., & Brown, B. (2021). Asynchronous discussion forums: Five learning designs.

Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2001). Learner experience and efficiency of instructional guidance. Educational Psychology, 21(1), 5–23.

Klepsch, M., & Seufert, T. (2020). Understanding instructional design effects by differentiated measurement of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Instructional Science, 48(1), Article 1.

Krahenbuhl, K. S. (2016). Student-centered Education and Constructivism: Challenges, Concerns, and Clarity for Teachers. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 89(3), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2016.1191311

Lange, C., Gorbunova, A., Shcheglova, I., & Costley, J. (2022). Direct instruction, worked examples and problem solving: The impact of instructional strategies on cognitive load. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1–13.

Lapitan Jr, L. D., Tiangco, C. E., Sumalinog, D. A. G., Sabarillo, N. S., & Diaz, J. M. (2021). An effective blended online teaching and learning strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education for Chemical Engineers, 35, 116–131.

Lee, J. W. (2020). The roles of online instructional facilitators and student performance of online class activity. Lee, Jung Wan (2020). The Roles of Online Instructional Facilitators and Student Performance of Online Class Activity. Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business, 7(8), 723–733.

Li, L., Xu, L. D., He, Y., He, W., Pribesh, S., Watson, S. M., & Major, D. A. (2021). Facilitating online learning via zoom breakout room technology: A case of pair programming involving students with learning disabilities. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 48(1), 12.

Lyman, F. (1981). Strategies for Reading Comprehension Think Pair Share. Unpublished Paper. University of Maryland Paper. Http://Www. Roe13. K12. Il.

Mintzes, J. J. (2020). From constructivism to active learning in college science. Active Learning in College Science: The Case for Evidence-Based Practice, 3–12.

Misra, F., & Mazelfi, I. (2021). Long-distance online learning during pandemic: The role of communication, working in group, and self-directed learning in developing student’s confidence. 225–234.

Murphy, J. T. (2023). Advice | 5 Ways to Ease Students Off the Lecture and Into Active Learning. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/5-ways-to-ease-students-off-the-lecture-and-onto-active-learning

Nerantzi, C. (2020). The use of peer instruction and flipped learning to support flexible blended learning during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 7(2), 184–195.

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2021). Balancing technology, pedagogy and the new normal: Post-pandemic challenges for higher education. Postdigital Science and Education, 3(3), 715–742.

Rincon-Flores, E. G., & Santos-Guevara, B. N. (2021). Gamification during Covid-19: Promoting active learning and motivation in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(5), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.7157

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge building. The Cambridge.

Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories an educational perspective. Pearson Education, Inc.

Seethamraju, R. (2014). Effectiveness of using online discussion forum for case study analysis. Education Research International, 2014.

Slocum, T. A., & Rolf, K. R. (2021). Features of direct instruction: Content analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(3), 775–784.

Sutarto, S., Sari, D. P., & Fathurrochman, I. (2020). Teacher strategies in online learning to increase students’ interest in learning during COVID-19 pandemic. Jurnal Konseling Dan Pendidikan, 8(3), 129–137.

Sweller, J. (2020). Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 1–16.

Tan, H. R., Chng, W. H., Chonardo, C., Ng, M. T. T., & Fung, F. M. (2020). How chemists achieve active learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic: Using the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework to support remote teaching. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 2512–2518.

Varvara, G., Bernardi, S., Bianchi, S., Sinjari, B., & Piattelli, M. (2021). Dental Education Challenges during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period in Italy: Undergraduate Student Feedback, Future Perspectives, and the Needs of Teaching Strategies for Professional Development. Healthcare, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040454

Zhang, L. (2022). Guidance differs between teaching modes: Practical challenges in integrating hands-on investigations with direct instruction. Learning: Research and Practice, 8(2), 96–115.

Zhang, L., & Cobern, W. W. (2021). Confusions on “guidance” in inquiry-based science teaching: A response to Aditomo and Klieme (2020). Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 21, 207–212.

Zhang, L., Kirschner, P. A., Cobern, W. W., & Sweller, J. (2022). There is an evidence crisis in science educational policy. Educational Psychology Review, 34(2), 1157–1176.

Zou, D., & Xie, H. (2019). Flipping an English writing class with technology-enhanced just-in-time teaching and peer instruction. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1127–1142.

Abstract - Active learning strategies tend to originate from one of two dominant philosophical perspectives. The first position is active learning as an instructional philosophy, whereby inquiry-based and discovery learning are primary modalities for acquiring new information. The second perspective considers active learning a strategy to supplement the use of more structured forms of instruction, such as direct instruction. From the latter perspective, active learning is employed to reinforce conceptual learning following the presentation of factual or foundational knowledge. This review focuses on the second perspective and uses of active learning as a strategy. We highlight the need and often overlooked requirement for including instructional guidance to ensure active learning, which can be effective and efficient for learning and learners.

Keywords - Active learning, instructional guidance, design strategy, cognitive load, efficiency, online and blended courses

Introduction

Learner engagement in online courses has been a central theme in educational research for several years (Martin, Sun and Westing, 2020). As we consider the academic experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2020 and started to subside in 2022, it is essential to reflect on the importance of course quality (Cavanaugh, Jacquemin and Junker, 2023) and learner experience in online courses (Gherghel, Yasuda and Kita, 2023). Rebounding from our collected experience, learner engagement continues to be an important element of course design and delivery. This fact was highlighted in 2021, when the United States Department of Education (DOE) set forth new standards for institutions offering online courses. To be eligible for Title IV funding, new standards require non-correspondence courses to ensure regular and substantive interactions (RSI) between instructors and students (Downs, 2021). This requirement necessitates the need to find ways to engage students allowing instructors the ability to maximize their interactions. One possible solution is to use active learning techniques that have been shown to increase student engagement and learning outcomes (Ashiabi & O’ Neal, 2008; Cavanaugh et al., 2023).

Active learning is an important instructional strategy and pedagogical philosophy used to design quality learning experiences and foster engaging and interactive learning environments. However, this is not a novel perspective. Many years ago in their seminal work, Chickering and Gamson (1987) discussed the issue of interaction between instructors and students, suggesting that this was an essential practice for quality undergraduate education. The newfound focus on active learning strategies has become more pronounced following an examination of instructional practices from 2020 to 2022. For example, Tan, Chng, Chonardo, Ng and Fung (2020) examined how chemistry instructors incorporated active learning into their instruction to achieve equivalent learning experiences in pre-pandemic classrooms. Similarly, Misra and Mazelfi (2021) described the need to incorporate group work or active learning activities into remote courses to: ‘increase students’ learning motivation, enforce mutual respect for friends’ opinions, foster excitement’ (p. 228). Rincon-Flores & Santos-Guevara (2021) found that gamification as a form of active learning, ‘helped to motivate students to participate actively and improved their academic performance, in a setting where the mode of instruction was remote, synchronous, and online’ (p.43). Further, the implementation of active learning, particularly gamification, was found to be helpful for promoting a more humanizing learning experience (Rincon-Flores & Santos-Guevara, 2021).

This review examines the use of active learning and presents instructional guidance as an often-overlooked element that must be included to make active learning useful and effective. The omission of explicit and direct instructional guidance when using active learning can be inefficient, resulting in an extraneous cognitive burden on learners (Lange, Gorbunova, Shcheglova and Costley, 2022). We hope to outline our justification through a review of active learning and offer strategies to ensure that the implementation of active learning is effective.

Active Learning as an Instructional Philosophy

Active learning is inherently a ‘student-centered’ instructional paradigm that is derived from a constructivist epistemological perspective (Krahenbuhl, 2016; Schunk, 2012). Constructivism theorizes that individuals construct their understanding through interactions and engagements, whereby the refinement of skills and knowledge results over time (Cobb & Bowers, 1999). Through inquiry, students produce experiences and make connections that lead to logical and conceptual growth (Bada & Olusegun, 2015). Engaging learners in activities, tasks, and planned experiences is an overarching premise of active learning as an instructional philosophy. As an overarching instructional philosophy, the role of instructional guidance can be minimized. As Hammer (1997) pointed out many years ago, the role of the instructor in these environments is to provide content and materials, and students are left make ‘discoveries’ through inquiry.

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is an instructional practice that falls under the general category of ‘active learning’. The tenets of IBL adhere to a constructivist learning philosophy (de Jong et al., 2023) and can be characterized by the following six elements (Duncan & Chinn, 2021). Students will:

Generate knowledge through investigation of a novel issue or problem.

Work ‘actively’ to discover new findings.

Use of evidence to derive conclusions.

Take responsibility for their own learning through ‘epistemological agency’ (Chinn & Iordanou, 2023) and share their learning with a community of learners.

Use problem-solving and reasoning for complex tasks.

Collaborate, share ideas, and derive solutions with peers.

Historically, inquiry-based learning as a form of active learning was adopted as an overall instructional paradigm in disciplines such as medicine and was closely aligned with problem-based learning (PBL) (Barrows, 1996). Proponents of PBL advocate its use because of its emphasis on the development of skills such as communication, collaboration, and critical thinking (Dring, 2019). Critics of these constructivist approaches to instruction highlight the absence of a structure and any form of instructional guidance (Zhang & Cobern, 2021). Instead, they advocate a more explicit form of instruction such as direct instruction (Zhang, Kirschner, Corben and Sweller, 2022).

The view that a hybrid of IBL coupled with direct instruction is the optimal approach to implementing active learning has been highlighted in the recent academic literature (de Jong et al., 2023). The authors suggest that the selection of direct instruction or active learning strategies, such as IBL, should be guided by the desired outcomes of instruction. If the goal of instruction is the acquisition of more foundational or factual information, direct instruction is the preferred strategy. Conversely, IBL strategies are more appropriate ‘for the promotion of deep understanding and transferrable conceptual understanding of topics that are open-ended or susceptible to misconceptions’ (de Jong et al., 2023 p. 7).

The recommendation to use both direct instruction and approaches like IBL has reframed active learning as an instructional strategy rather than an overarching pedagogical philosophy. Active learning should be viewed as a technique or strategy coupled with direct instructional approaches (de Jong et al., 2023).

Active Learning as an Instructional Strategy

Approaching active learning as an instructional strategy rather than an overarching instructional philosophy helps clarify and address the varying perspectives found in the literature. Zhang et al. (2022) suggested that there is a push to emphasize exploration-based pedagogy. This includes instructional approaches deemed to be predicated on inquiry, discovery, or problem-based approaches. This emphasis has resulted in changes to curricular policies that mandate the incorporation of these instructional philosophies. Zhang et al. (2022) discussed how active learning approaches can be incorporated into science education policy to emphasize ‘inquiry’ approaches, despite adequate evidence for effectiveness. Zhang et al. (2022) stated that the ‘disjoint between policy documents and research evidence is exacerbated by the tendency to ignore categories of research that do not provide the favored research outcomes that support teaching science through inquiry and investigations’ (p. 1162). Instead, Zhang et al. (2022) advocate for direct instruction as the primary mode of instruction in science education with active learning or ‘inquiry’ learning incorporated as a strategy, arguing that conceptual or foundational understanding ‘should not be ‘traded off’ by prioritizing other learning outcomes’ (p. 1172).

In response to Zhang et al. ’s (2022) critique, de Jong et al. (2023) argued that research evidence supports the use of inquiry-based instruction for the acquisition of conceptual understanding in science education. They asserted that both inquiry-based (or active learning approaches) and direct instruction serve specific learning needs. Direct instruction may be superior for foundational or factual learning, while inquiry-based or active learning may be better for conceptual understanding and reinforcement. The conclusion of de Jong et al. ’s (2023) argument suggests the use of a hybrid of direct instruction and active learning techniques, such as inquiry-based designs, depending on the stated learning objectives of the course or the desired outcomes.

This hybrid approach to instructional practice can help ensure that intended learning outcomes are matched with effective instructional strategies. Furthermore, a hybrid approach can help maintain efficiency in learning rather than leaving the acquisition of stated learning outcomes to discovery or happenstance (Slocum & Rolf, 2021). This notion was supported by Nerantzi's (2020) suggestion that ‘students learn best when they are active and immersed in the learning process, when their curiosity is stimulated, when they can ask questions and debate in and outside the classroom, when they are supported in this process and feel part of a learning community’ (p. 187). Emphasis on learner engagement may support the belief that active learning strategies combined with direct instruction may provide an optimal environment for learning. Active learning strategies can be used to reinforce the direct or explicit presentation of concepts and principles (Lapitan Jr, Tiangco, Sumalinog, Sabarillo and Diaz, 2021).

Recently, Zhang (2022) examined the importance of integrating direct instruction with hands-on investigation as an instructional model in high school physics classes. Zhang (2022) determined that ‘students benefit more when they develop a thorough theoretical foundation about science ideas before hands-on investigations’ (p. 111). This supports the earlier research in post-secondary STEM disciplines as reported by Freeman, Eddy, McDonough and Wenderoth (2014), where the authors suggested that active learning strategies help to improve student performance. The authors further predicted that active learning interventions would show more significant learning gains when combined with ‘required exercises that are completed outside of formal class sessions’ (p. 8413).

Active Learning Strategies

Active learning is characterized by activities, tasks, and learner interactions. Several characteristics of active learning have been identified, including interaction, peer learning, and instructor presence (Nerantzi, 2020). Technology affords students learning opportunities to connect pre-, during-, and post-formal learning sessions (Zou & Xie, 2019; Nerantzi, 2020). The interactions or techniques that instructors use help determine the types of interactions and outcomes that will result. Instructors may be ‘present’ or active in the process but may not provide adequate instructional guidance for techniques to be efficient or effective (Cooper, Schinske and Tanner, 2021; Kalyuga, Chandler and Sweller. 2001). To highlight this gap, we first consider the widely used technique of think-pair-share, an active learning strategy first introduced by Lyman (1981). This active learning strategy was introduced to provide all students equitable opportunities to think and discuss ideas with their peers. The steps involved in this technique were recently summarized (Cooper et al., 2021): i) provide a prompt or question to students, (ii) give students a chance to think about the question or prompt independently, (iii) have students share their initial answers/responses with a neighbor in a pair or a small group, and (iv) invite a few groups a chance to share their responses with the whole class.