We found 353 results that contain "online"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Instructional Technology and Development Staff Bio - Dr. Cierra Presberry

Dr. Cierra Presberry

Title

Curriculum Development Specialist, Instructional Technology and Development Team

Education

Bachelor’s in Special Education, Michigan State University

Master’s in Teaching and Curriculum, Michigan State University

PhD in Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education, Michigan State University

Work Experience

My career started in Detroit, where I was a special education teacher at the elementary and secondary levels. During my doctoral program at MSU, I taught a variety of courses within the teacher preparation program in the areas of literacy and social studies. In my current role as a curriculum development specialist, I work with instructors to improve the quality of the online components of their courses.

Professional Interests

I am particularly interested in addressing issues of equity and ensuring that all students have access to the education they deserve.

Title

Curriculum Development Specialist, Instructional Technology and Development Team

Education

Bachelor’s in Special Education, Michigan State University

Master’s in Teaching and Curriculum, Michigan State University

PhD in Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education, Michigan State University

Work Experience

My career started in Detroit, where I was a special education teacher at the elementary and secondary levels. During my doctoral program at MSU, I taught a variety of courses within the teacher preparation program in the areas of literacy and social studies. In my current role as a curriculum development specialist, I work with instructors to improve the quality of the online components of their courses.

Professional Interests

I am particularly interested in addressing issues of equity and ensuring that all students have access to the education they deserve.

Authored by:

Cierra Presberry

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Instructional Technology and Development Staff Bio - Dr. Cierra Presberry

Dr. Cierra Presberry

Title

Curriculum Development Specialist, Inst...

Title

Curriculum Development Specialist, Inst...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Friday, Oct 1, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

DISCIPLINARY CONTENT

Call for Proposals 2021-2022: Learning Communities

Learning Communities provide safe and supportive spaces for complicated conversations about curriculum and pedagogy. Michigan State University has supported these initiatives since 2004 and continues to do so through a funding program administered by the Academic Advancement Network.

Learning Communities at MSU are free to select their own topics and determine the structures that best support their inquiries. Accordingly, communities tend to vary greatly in their practices, interests, and agendas. All communities, however, share three things in common: they meet at least eight times across the academic year, explore important educational themes, and welcome all members of MSU’s instructional staff, regardless of rank or discipline.

Learning Communities run from September to April. Call for 2021-22 proposals goes out on May 17th with a due date of June 11th. If you are interested in joining or proposing a community, please look to the links at the right for more information.Review the MSU Learning Community Guidelines

Please propose ideas using this online formProposals are due by June 11, 2021.

Discover more about learning Communities

See past topics.

Learning Communities at MSU are free to select their own topics and determine the structures that best support their inquiries. Accordingly, communities tend to vary greatly in their practices, interests, and agendas. All communities, however, share three things in common: they meet at least eight times across the academic year, explore important educational themes, and welcome all members of MSU’s instructional staff, regardless of rank or discipline.

Learning Communities run from September to April. Call for 2021-22 proposals goes out on May 17th with a due date of June 11th. If you are interested in joining or proposing a community, please look to the links at the right for more information.Review the MSU Learning Community Guidelines

Please propose ideas using this online formProposals are due by June 11, 2021.

Discover more about learning Communities

See past topics.

Authored by:

Michael Lockett

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Call for Proposals 2021-2022: Learning Communities

Learning Communities provide safe and supportive spaces for complic...

Authored by:

DISCIPLINARY CONTENT

Monday, May 17, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

How can a first-year writing course help to create 21st century STEM students with foundations for interdisciplinary inquiry? Could such as curriculum engage STEM students in knowledge production in ways that help to acculturate them as collaborative, ethical, and empathetic learners? Bringing together insights from writing pedagogy, work on critical science literacy, and science studies, this round-table is hosted by the collaborative team leading an effort to rethink the first year writing course required of all students at Lyman Briggs College, MSU's residential college for STEM students. A major goal of the curriculum redesign is to develop science studies-inspired writing assignments that foster reflective experiential learning about the nature of science. The purpose of this approach is not only to demonstrate the value of inquiry in science studies (history, philosophy, and sociology of science) to STEM students as they pursue their careers, but to foster diverse inclusion in science by demystifying key aspects of scientific culture and its hidden curriculum for membership. Following the guidance of critical pedagogy (e.g. bell hooks), we aim to use the context of first-year writing instruction as an opportunity for critical reflection and empowerment. The roundtable describes how the instructional team designed the first-year curriculum and adapted it to teaching online during the pandemic, and shares data on lessons learned by both the instructor team and our students. We invite participants to think with us as we continue to iteratively develop and assess the curriculum.To access a PDF version of the "Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies" poster, click here. Description of Poster:

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

Marisa Brandt, HPS Lyman Briggs College & June Oh, English

Project Overview: Reimagining LB 133

Lyman Briggs College aims to provide a high quality science education to diverse students by teaching science in social, human, and global contexts. LB 133: Science & Culture fulfills the Tier 1 writing requirement for 80-85% of LBC students. Starting in F19, we implemented a new, collaboratively developed and taught cohort model of the LB 133 curriculum in order to take advantage of opportunity to foster a community of inquiry, inclusion, and curiosity.

First year college writing and literacy courses aim to give students skills to communicate and evaluate information in their own fields and beyond. While teaching important writing skills, LB 133 focuses on developing students’ science literacy by encouraging them to enact a subject position of a socially engaged science professional in training. LB 133 was designed based on ideas of HPS.

History, Philosophy, and Sociology (HPS) or “science studies” is an interdisciplinary field that studies science in context, often extended to include medicine, technology, and other sites of knowledge-production. LB 133 centers inquiry into relations of science and culture. One way HPS can help students succeed in STEM is by fostering inclusion. In LB 133, this occurs through demystifying scientific culture and hidden curriculum through authentic, project-based inquiry.

Like WRAC 110, LB 133 is organized around five writing projects. Each project entails a method of inquiry into science as a social, human practice and teaches them to write first as a form of sense-making about their data. (Column 2) Then, students develop writing projects to communicate what they have learned to non-scientific audiences.

Research Questions:

How did their conceptions of science change?[Text Wrapping Break] 2. Did their writing improve?[Text Wrapping Break] 3. What did they see as the most important ideas and skills they would take from the course?[Text Wrapping Break] 4. Did they want more HPS at LBC?

Data Collection:

[Text Wrapping Break]1. Analysis of the beginning and end of course Personal Writing assessments. [Text Wrapping Break]2. End of term survey. [Text Wrapping Break]3. Answers to course reflection questions.

Selected Results: See Column 3.

Conclusions: The new model seems successful! Students reported finding 133 surprisingly enjoyable and educational, for many reasons. Many felt motivated to write about science specifically, saw communication as valuable scientific skill. Most felt their writing improved and learned more than anticipated. Most learned and valued key HPS concepts and wanted to learn more about diversity in scientific cultures, and wanted to continue HPS education in LBC to do so.

Column 2 - Course Structure: Science & Culture

Assessment

Science Studies Content[Text Wrapping Break]Learning Goals

Literacy & Writing Skills Learning Goals

Part 1 - Cultures of Science

Personal Writing 1: Personal Statement [STEM Ed Op-ed][Text Wrapping Break]Short form writing from scientific subject position.

Reflect on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Diagnostic for answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Scientific Sites Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of how a local lab produces knowledge.

Understand scientific practice, reasoning, and communication in its diverse social, material, and cultural contexts. Demystify labs and humanize scientists.

Making observational field notes. Reading scientific papers.

Peer review. Claim, evidence, reasoning. Writing analytical essays based on observation.

Part 2 - Science in Culture

Unpacking a Fact Poster

Partner project assessing validity of a public scientific claim.

Understand the mediation of science and how to evaluate scientific claims. Identify popular conceptions of science and contrast these with scientists’ practices.

Following sources upstream. Comparing sources.

APA citation style.

Visual display of info on a poster.

Perspectives Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of a debate concerning science in Michigan.

Identify and analyze how diverse stakeholders are included in and/or excluded from science. Recognize value of diverse perspective.

Find, use, and correctly cite primary and scholarly secondary sources from different stakeholder perspectives.

Learn communicating to a broader audience in an online platform.

Personal Writing 2: Letter + PS Revision[Text Wrapping Break]Sharing a course takeaway with someone.

Reflect again on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Final assessment of answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Weekly Formative Assessments

Discussion Activities Pre-meeting writing about the readings

Reflect on prompted aspects of science and culture

Writing as critical inquiry.

Note-taking.

Preparation for discussion.

Curiosity Colloquium responses

200 words reflecting on weekly speaker series

Exposure to college, campus, and academic guests—including diverse science professionals— who share their curiosity and career story.

Writing as reflection on presentations and their personal value.

Some presenters share research and writing skills.

Column 3 - Results

Results from Personal Writing

Fall 19: There were largely six themes the op-ed assignments discussed. Majority of students chose to talk about the value of science in terms of its ubiquity, problem-solving skills and critical thinking skills, and the way it prompts technological innovation.

Fall 21: Students largely focused on 1. the nature of science as a product of human labor research embedded with many cultural issues, and 2. science as a communication and how scientists can gain public trust (e.g., transparency, collaboration, sharing failure.)

F19 & S20 Selected Survey Results

108 students responding.The full report here.

92.5% reported their overall college writing skills improved somewhat or a lot.

76% reported their writing skills improved somewhat or a lot more than they expected.

89% reported planning to say in LBC.

Selected Course Reflection Comments

The most impactful things students report learning at end of semester.

Science and Culture: Quotes: “how scientific knowledge is produced” “science is inherently social” “how different perspectives . . . impact science” “writing is integral to the scientific community as a method of sharing and documenting scientific research and discoveries”

Writing: Quotes: “a thesis must be specific and debatable” “claim, evidence, and reasoning” “it takes a long time to perfect.” Frequently mentioned skills: Thesis, research skill (citation, finding articles and proper sources), argument (evidence), structure and organization skills, writing as a (often long and arduous) process, using a mentor text, confidence.

What do you want to learn more about after this course?

“How culture(s) and science coexist, and . . . how different cultures view science”

“Gender and minority disparities in STEM” “minority groups in science and how their cultures impact how they conduct science” “different cultures in science instead of just the United States” “how to write scientific essays”

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

Marisa Brandt, HPS Lyman Briggs College & June Oh, English

Project Overview: Reimagining LB 133

Lyman Briggs College aims to provide a high quality science education to diverse students by teaching science in social, human, and global contexts. LB 133: Science & Culture fulfills the Tier 1 writing requirement for 80-85% of LBC students. Starting in F19, we implemented a new, collaboratively developed and taught cohort model of the LB 133 curriculum in order to take advantage of opportunity to foster a community of inquiry, inclusion, and curiosity.

First year college writing and literacy courses aim to give students skills to communicate and evaluate information in their own fields and beyond. While teaching important writing skills, LB 133 focuses on developing students’ science literacy by encouraging them to enact a subject position of a socially engaged science professional in training. LB 133 was designed based on ideas of HPS.

History, Philosophy, and Sociology (HPS) or “science studies” is an interdisciplinary field that studies science in context, often extended to include medicine, technology, and other sites of knowledge-production. LB 133 centers inquiry into relations of science and culture. One way HPS can help students succeed in STEM is by fostering inclusion. In LB 133, this occurs through demystifying scientific culture and hidden curriculum through authentic, project-based inquiry.

Like WRAC 110, LB 133 is organized around five writing projects. Each project entails a method of inquiry into science as a social, human practice and teaches them to write first as a form of sense-making about their data. (Column 2) Then, students develop writing projects to communicate what they have learned to non-scientific audiences.

Research Questions:

How did their conceptions of science change?[Text Wrapping Break] 2. Did their writing improve?[Text Wrapping Break] 3. What did they see as the most important ideas and skills they would take from the course?[Text Wrapping Break] 4. Did they want more HPS at LBC?

Data Collection:

[Text Wrapping Break]1. Analysis of the beginning and end of course Personal Writing assessments. [Text Wrapping Break]2. End of term survey. [Text Wrapping Break]3. Answers to course reflection questions.

Selected Results: See Column 3.

Conclusions: The new model seems successful! Students reported finding 133 surprisingly enjoyable and educational, for many reasons. Many felt motivated to write about science specifically, saw communication as valuable scientific skill. Most felt their writing improved and learned more than anticipated. Most learned and valued key HPS concepts and wanted to learn more about diversity in scientific cultures, and wanted to continue HPS education in LBC to do so.

Column 2 - Course Structure: Science & Culture

Assessment

Science Studies Content[Text Wrapping Break]Learning Goals

Literacy & Writing Skills Learning Goals

Part 1 - Cultures of Science

Personal Writing 1: Personal Statement [STEM Ed Op-ed][Text Wrapping Break]Short form writing from scientific subject position.

Reflect on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Diagnostic for answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Scientific Sites Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of how a local lab produces knowledge.

Understand scientific practice, reasoning, and communication in its diverse social, material, and cultural contexts. Demystify labs and humanize scientists.

Making observational field notes. Reading scientific papers.

Peer review. Claim, evidence, reasoning. Writing analytical essays based on observation.

Part 2 - Science in Culture

Unpacking a Fact Poster

Partner project assessing validity of a public scientific claim.

Understand the mediation of science and how to evaluate scientific claims. Identify popular conceptions of science and contrast these with scientists’ practices.

Following sources upstream. Comparing sources.

APA citation style.

Visual display of info on a poster.

Perspectives Portfolio[Text Wrapping Break]Collaborative investigation of a debate concerning science in Michigan.

Identify and analyze how diverse stakeholders are included in and/or excluded from science. Recognize value of diverse perspective.

Find, use, and correctly cite primary and scholarly secondary sources from different stakeholder perspectives.

Learn communicating to a broader audience in an online platform.

Personal Writing 2: Letter + PS Revision[Text Wrapping Break]Sharing a course takeaway with someone.

Reflect again on evolving identity, role, and responsibilities in scientific culture.

Final assessment of answering questions, supporting a claim, providing evidence, structure, and clear writing.

Weekly Formative Assessments

Discussion Activities Pre-meeting writing about the readings

Reflect on prompted aspects of science and culture

Writing as critical inquiry.

Note-taking.

Preparation for discussion.

Curiosity Colloquium responses

200 words reflecting on weekly speaker series

Exposure to college, campus, and academic guests—including diverse science professionals— who share their curiosity and career story.

Writing as reflection on presentations and their personal value.

Some presenters share research and writing skills.

Column 3 - Results

Results from Personal Writing

Fall 19: There were largely six themes the op-ed assignments discussed. Majority of students chose to talk about the value of science in terms of its ubiquity, problem-solving skills and critical thinking skills, and the way it prompts technological innovation.

Fall 21: Students largely focused on 1. the nature of science as a product of human labor research embedded with many cultural issues, and 2. science as a communication and how scientists can gain public trust (e.g., transparency, collaboration, sharing failure.)

F19 & S20 Selected Survey Results

108 students responding.The full report here.

92.5% reported their overall college writing skills improved somewhat or a lot.

76% reported their writing skills improved somewhat or a lot more than they expected.

89% reported planning to say in LBC.

Selected Course Reflection Comments

The most impactful things students report learning at end of semester.

Science and Culture: Quotes: “how scientific knowledge is produced” “science is inherently social” “how different perspectives . . . impact science” “writing is integral to the scientific community as a method of sharing and documenting scientific research and discoveries”

Writing: Quotes: “a thesis must be specific and debatable” “claim, evidence, and reasoning” “it takes a long time to perfect.” Frequently mentioned skills: Thesis, research skill (citation, finding articles and proper sources), argument (evidence), structure and organization skills, writing as a (often long and arduous) process, using a mentor text, confidence.

What do you want to learn more about after this course?

“How culture(s) and science coexist, and . . . how different cultures view science”

“Gender and minority disparities in STEM” “minority groups in science and how their cultures impact how they conduct science” “different cultures in science instead of just the United States” “how to write scientific essays”

Authored by:

Marisa Brandt & June Oh

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Reimagining First-Year Writing for STEM Undergraduates as Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Studies

How can a first-year writing course help to create 21st century STE...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Thursday, May 6, 2021

Posted on: MSU Online & Remote Teaching

ASSESSING LEARNING

Assessment strategy for remote teaching

With our guiding principles for remote teaching as flexibility, generosity, and transparency, we know that there is no one solution for assessment that will meet all faculty and student needs. From this perspective, the primary concern should be assessing how well students have achieved the key learning objectives and determining what objectives are still unmet. It may be necessary to modify the nature of the exam to allow for the differences of the remote environment. This document, written for any instructor who typically administers an end-of semester high-stakes final exam, addresses how best to make those modifications.

Check out the full resource here, and read more about the three primary alternatives to a semester-end final:

1) Multiple lower-stakes assessments (most preferred)2) Open note exams (preferred)3) Online proctored exams (if absolutely necessary)

Check out the full resource here, and read more about the three primary alternatives to a semester-end final:

1) Multiple lower-stakes assessments (most preferred)2) Open note exams (preferred)3) Online proctored exams (if absolutely necessary)

Authored by:

4.0 International (CC by 4.0)

Posted on: MSU Online & Remote Teaching

Assessment strategy for remote teaching

With our guiding principles for remote teaching as flexibility, gen...

Authored by:

ASSESSING LEARNING

Monday, May 4, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Optional Syllabus Statements: Inclusion

The following are a optional Inclusion Statements to include on your syllabus:

Michigan State University is committed to providing access and promoting/protecting freedom of speech in an inclusive learning environment. Discrimination and harassment based on a protected identity are prohibited. Please review MSU’s Notice of Non-Discrimination, Anti-Harassment, and Non-Retaliation.

In this class, we will work together to create and maintain a respectful teaching and learning environment where we engage in conversations that challenge our perspectives and understanding.

Please let me know if you would like me to use a name for you that is not reflected in the University system or if there is anything else I can do to support your access to this class.

Language that should NOT be included in a syllabus

Language that appears to promote protected identity-based preferences or otherwise violates federal or state civil rights laws

Language that appears to restrict First Amendment rights

References to any “policy” that is not a University or unit-level policy

Also, for your reference:Religious Observances & Holidays: Michigan State University has long had a policy to permit students, faculty/academic staff, and support staff to observe those holidays set aside by their chosen religious faith.

Links to the policies can be found below:

Religious Observance Policy (students, faculty, academic staff)

Support Staff Policy for Observance of Religious Holidays (support staff)

More information about religious holidays and traditions can be found online.

Interfaith Calendar

Center for Spiritual and Ethical Education

Ramadan at MSU

Provisional Land Acknowledgement: (This paragraph is intended to be read at the beginning of formal events or published in printed material.)

We collectively acknowledge that Michigan State University occupies the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg – Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples. In particular, the University resides on Land ceded in the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw. We recognize, support, and advocate for the sovereignty of Michigan’s twelve federally-recognized Indian nations, for historic Indigenous communities in Michigan, for Indigenous individuals and communities who live here now, and for those who were forcibly removed from their Homelands. By offering this Land Acknowledgement, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold Michigan State University more accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.Visit MSU's American Indian and Indigenous Studies page for more information on Land Acknowledgements.

Michigan State University is committed to providing access and promoting/protecting freedom of speech in an inclusive learning environment. Discrimination and harassment based on a protected identity are prohibited. Please review MSU’s Notice of Non-Discrimination, Anti-Harassment, and Non-Retaliation.

In this class, we will work together to create and maintain a respectful teaching and learning environment where we engage in conversations that challenge our perspectives and understanding.

Please let me know if you would like me to use a name for you that is not reflected in the University system or if there is anything else I can do to support your access to this class.

Language that should NOT be included in a syllabus

Language that appears to promote protected identity-based preferences or otherwise violates federal or state civil rights laws

Language that appears to restrict First Amendment rights

References to any “policy” that is not a University or unit-level policy

Also, for your reference:Religious Observances & Holidays: Michigan State University has long had a policy to permit students, faculty/academic staff, and support staff to observe those holidays set aside by their chosen religious faith.

Links to the policies can be found below:

Religious Observance Policy (students, faculty, academic staff)

Support Staff Policy for Observance of Religious Holidays (support staff)

More information about religious holidays and traditions can be found online.

Interfaith Calendar

Center for Spiritual and Ethical Education

Ramadan at MSU

Provisional Land Acknowledgement: (This paragraph is intended to be read at the beginning of formal events or published in printed material.)

We collectively acknowledge that Michigan State University occupies the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg – Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples. In particular, the University resides on Land ceded in the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw. We recognize, support, and advocate for the sovereignty of Michigan’s twelve federally-recognized Indian nations, for historic Indigenous communities in Michigan, for Indigenous individuals and communities who live here now, and for those who were forcibly removed from their Homelands. By offering this Land Acknowledgement, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold Michigan State University more accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.Visit MSU's American Indian and Indigenous Studies page for more information on Land Acknowledgements.

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Optional Syllabus Statements: Inclusion

The following are a optional Inclusion Statements to include on you...

Posted by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Monday, Aug 18, 2025

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

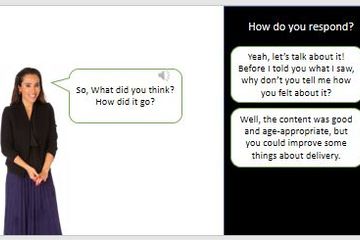

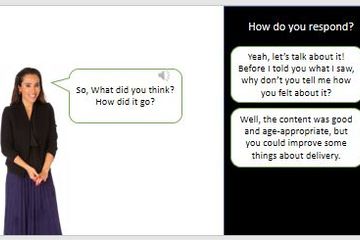

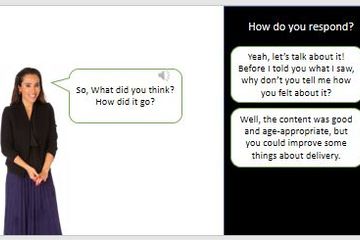

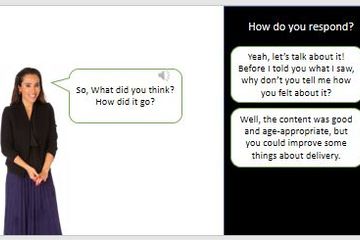

Using Learning Scenarios

Learning Scenarios

Whether you are teaching traditional credit-bearing courses, teaching in community outreach or Extension, or working in employee development, learning scenarios are a tool you don’t want to overlook.

Scenarios use problems to grab learners' attention and emotion to make learning stick. They reflect the reality that real life isn’t black and white. They are a great solution when learners need to solve a problem, make a decision, or apply their learning in the real world. They align to andragogical principles of autonomy, problem-based learning orientation, and the importance of tapping into learners' experiences.

eLearning modules that make heavy use of scenarios are often authored in pricey software such as Articulate Storyline. ($499/year for educators. See some examples of scenarios created in Storyline.) Not an option for most of us! But you can think creatively and have similar results with other tools you have at your disposal.Desire2LearnIn Desire2Learn, you can use the self-assessments feature to present a simple scenario, and it allows you to add images and video. Then the multiple-choice options can be the various solutions to choose from. When you click on one, you get instant feedback. See the screen shot below. Easy and simple, but not very flexible or aesthetically pleasing, and you can't have branching scenarios. Another option is discussion forums- you can embed a scenario using images, video, and/or text into a discussion forum, and ask learners to post what they would do next or how to solve the dilemma.

CamtasiaTechsmith's Camtasia video-editing software has some interactive features that allow you to present a scenario as a video, and then follow it up with a multiple choice question. The question is essentially embedded into the video, but the video is played within the special Techsmith video player.

In the (somewhat silly) example below, the video is hosted in Techsmith's Screencast online storage account, and then the embed code can be copied into Desire2Learn and inserted using the "Insert Stuff" button and then selecting "Enter Embed Code" and pasting the code.

PowerPointPowerPoint can also be used. In a synchronous setting, use the slides to contextualize the scenario with images and text, and have learners discuss possible solutions or outcomes, or use them asynchronously in a way that allows for branching scenarios like this one:EXAMPLE: Click this link then launch the .pptx presentation in slide show view.

To create a branching scenario like this, you need to follow the following steps.

Plan it out

Use whatever suits you- pen and paper, Power Point, flowcharting software- to plan the scenario and what happens next after a choice is made. An example of a plan for a branching scenario (done in Power Point) is below. Planning it all out helps you quickly build the slides and then link to the right place.

Build the slides and add the links.

Create the buttons which are the clickable choices using shapes. Then select it and right click on the shape. Select Link and then select Place in this document. You then select the slide it would link to. Repeat for all choices.

Change settings to force learners to click a button and not use arrow keys

Under the Slide Show tab, select Set Up Slide Show. Select the option of Browsed at a kiosk (full screen).

Whether you are teaching traditional credit-bearing courses, teaching in community outreach or Extension, or working in employee development, learning scenarios are a tool you don’t want to overlook.

Scenarios use problems to grab learners' attention and emotion to make learning stick. They reflect the reality that real life isn’t black and white. They are a great solution when learners need to solve a problem, make a decision, or apply their learning in the real world. They align to andragogical principles of autonomy, problem-based learning orientation, and the importance of tapping into learners' experiences.

eLearning modules that make heavy use of scenarios are often authored in pricey software such as Articulate Storyline. ($499/year for educators. See some examples of scenarios created in Storyline.) Not an option for most of us! But you can think creatively and have similar results with other tools you have at your disposal.Desire2LearnIn Desire2Learn, you can use the self-assessments feature to present a simple scenario, and it allows you to add images and video. Then the multiple-choice options can be the various solutions to choose from. When you click on one, you get instant feedback. See the screen shot below. Easy and simple, but not very flexible or aesthetically pleasing, and you can't have branching scenarios. Another option is discussion forums- you can embed a scenario using images, video, and/or text into a discussion forum, and ask learners to post what they would do next or how to solve the dilemma.

CamtasiaTechsmith's Camtasia video-editing software has some interactive features that allow you to present a scenario as a video, and then follow it up with a multiple choice question. The question is essentially embedded into the video, but the video is played within the special Techsmith video player.

In the (somewhat silly) example below, the video is hosted in Techsmith's Screencast online storage account, and then the embed code can be copied into Desire2Learn and inserted using the "Insert Stuff" button and then selecting "Enter Embed Code" and pasting the code.

PowerPointPowerPoint can also be used. In a synchronous setting, use the slides to contextualize the scenario with images and text, and have learners discuss possible solutions or outcomes, or use them asynchronously in a way that allows for branching scenarios like this one:EXAMPLE: Click this link then launch the .pptx presentation in slide show view.

To create a branching scenario like this, you need to follow the following steps.

Plan it out

Use whatever suits you- pen and paper, Power Point, flowcharting software- to plan the scenario and what happens next after a choice is made. An example of a plan for a branching scenario (done in Power Point) is below. Planning it all out helps you quickly build the slides and then link to the right place.

Build the slides and add the links.

Create the buttons which are the clickable choices using shapes. Then select it and right click on the shape. Select Link and then select Place in this document. You then select the slide it would link to. Repeat for all choices.

Change settings to force learners to click a button and not use arrow keys

Under the Slide Show tab, select Set Up Slide Show. Select the option of Browsed at a kiosk (full screen).

Authored by:

Anne Baker

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Using Learning Scenarios

Learning Scenarios

Whether you are teaching traditional credit-bear...

Whether you are teaching traditional credit-bear...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, Aug 18, 2021

Posted on: Educator Stories

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Kathy Hadley's Educator Story

This week, we are featuring Dr. Kathy Hadley, Assistant Professor in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures (WRAC). Kathy was recognized via iteach.msu.edu's Thank and Educator Initiative! We encourage MSU community members to nominate high-impact Spartan educators (via our Thank an Educator form) regularly!

Read more about Dr. Hadley’s perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by their responses!

You were recognized via the Thank an Educator Initiative. In one word, what does being an educator mean to you? What does this word/quality look like in your practice? Have your ideas on this changed over time? If so, how?

Now more than ever, empathy is essential to being an educator. I teach first-year writing in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures. My courses are highly interactive, but students struggle to learn when they’re overly stressed, anxious, or generally preoccupied. Early in the pandemic I participated in a great deal of training for best practices in online-teaching. What struck me was the emphasis not just on educational technology but on being a genuine caring presence for students and doing everything we can to help them, whether that means connecting them with university resources or simply being there for them. We also need to remember how much they’ve lost over the past couple of years and how those loses still resonate. I am fortunate to work in a department that recognizes these concerns and to teach a curriculum that encourages self-reflection. Teachers need to be flexible and understanding as students find their way back.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role? Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

One particular challenge is keeping students focused on their learning in a time of great stress, as I noted above. Academically, best practices include keeping students oriented to course plans and expectations; this can be as simple as frequent reminders about what we’re doing next and why it matters. More generally, best practices include a wholistic approach to students’ well-being in ways that help them move forward and succeed in the course rather than getting lost or drifting away.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

Over the past two years, especially, I’ve benefited greatly from the many resources available through WRAC, the College of Arts and Letters, and the university. Many of these resources are geared toward professional development, but there’s been a strong through-line of ensuring compassionate and empathic teaching practices. I am especially grateful to my WRAC colleagues and administrators for their collegiality and their extraordinary efforts on behalf of faculty and students through workshops, shared resources, and check-in sessions. I also rely, as always, on the MSU Library’s first-year writing teaching librarians and on making sure students are aware of the resources they have through the MSU Neighborhood Centers; the Writing Center; the English Language Lab; the Resource Center for Persons with Disabilities; and Counseling and Psychiatric Services.

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature!

Read more about Dr. Hadley’s perspectives below. #iteachmsu's questions are bolded below, followed by their responses!

You were recognized via the Thank an Educator Initiative. In one word, what does being an educator mean to you? What does this word/quality look like in your practice? Have your ideas on this changed over time? If so, how?

Now more than ever, empathy is essential to being an educator. I teach first-year writing in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures. My courses are highly interactive, but students struggle to learn when they’re overly stressed, anxious, or generally preoccupied. Early in the pandemic I participated in a great deal of training for best practices in online-teaching. What struck me was the emphasis not just on educational technology but on being a genuine caring presence for students and doing everything we can to help them, whether that means connecting them with university resources or simply being there for them. We also need to remember how much they’ve lost over the past couple of years and how those loses still resonate. I am fortunate to work in a department that recognizes these concerns and to teach a curriculum that encourages self-reflection. Teachers need to be flexible and understanding as students find their way back.

What is a challenge you experience in your educator role? Any particular “solutions” or “best practices” you’ve found that help you support student success at the university despite/in the face of this?

One particular challenge is keeping students focused on their learning in a time of great stress, as I noted above. Academically, best practices include keeping students oriented to course plans and expectations; this can be as simple as frequent reminders about what we’re doing next and why it matters. More generally, best practices include a wholistic approach to students’ well-being in ways that help them move forward and succeed in the course rather than getting lost or drifting away.

What are practices you utilize that help you feel successful as an educator?

Over the past two years, especially, I’ve benefited greatly from the many resources available through WRAC, the College of Arts and Letters, and the university. Many of these resources are geared toward professional development, but there’s been a strong through-line of ensuring compassionate and empathic teaching practices. I am especially grateful to my WRAC colleagues and administrators for their collegiality and their extraordinary efforts on behalf of faculty and students through workshops, shared resources, and check-in sessions. I also rely, as always, on the MSU Library’s first-year writing teaching librarians and on making sure students are aware of the resources they have through the MSU Neighborhood Centers; the Writing Center; the English Language Lab; the Resource Center for Persons with Disabilities; and Counseling and Psychiatric Services.

Don't forget to celebrate individuals you see making a difference in teaching, learning, or student success at MSU with #iteachmsu's Thank an Educator initiative. You might just see them appear in the next feature!

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: Educator Stories

Kathy Hadley's Educator Story

This week, we are featuring Dr. Kathy Hadley, Assistant Professor i...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, May 4, 2022

Posted on: MSU Online & Remote Teaching

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Remote participation quick guide

click the image above to access a PDF file of the quick guideRemote Participation and Student Engagement

This document provides an introduction to maintaining student engagement as you move to remote teaching. It outlines key steps to Plan, Modify, and Implement when making this move to optimize student learning. As with any steps you take in moving to remote teaching, it’s important to anchor your decisions in course learning objectives and to be transparent, flexible, and generous with students.

Plan

In planning how you will continue to engage students in your course, remember that interaction can occur between the student and you, the student and other students, and the student and the course materials.

Modify

When modifying in-class activities to a remote offering, you can start by cataloguing all of the ways people typically interact in your classroom. This list can then be used to identify particular digital strategies or technologies for adapting your current approach and translating your methods to an online space. For example, you might draft a table like the one below:

Interactions

Class Activity

Modify

Implement

Teacher to students:

During lecture, I ask questions to check student understanding.

Ask a poll question in a live Zoom session or D2L discussion forum whereas students respond to a prompt.

How to create a poll in Zoom:

https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/203749865-Polling-for-Webinars

How to manage D2L discussion forum:

https://documentation.brightspace.com/EN/le/discussions/learner/discussions_intro_1.htm

Student to material:

We watch and discuss a video.

Share a link with students in a variety of ways - i.e. post the link in a D2L discussion forum along with questions for response.

How to create a link in D2L: https://resources.depaul.edu/teaching-commons/teaching-guides/technology/desire2learn/tools/content/Pages/creating-links.aspx

Student to students:

I facilitate a classroom discussion and students respond to the prompt.

Create breakout rooms in a live Zoom session or a D2L discussion forum.

How to make and manage Zoom Breakout rooms: https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/206476313-Managing-Video-Breakout-Rooms

How to manage D2L discussion forum:

https://documentation.brightspace.com/EN/le/discussions/learner/discussions_intro_1.htm

Student to students:

I put students in small groups for more active discussions.

Create breakout rooms in a live Zoom session or D2L discussion forum whereas students respond to a prompt.

How to manage D2L discussion forum:

https://documentation.brightspace.com/EN/le/discussions/learner/discussions_intro_1.htm

Teacher to student:

I hold office hours to meet 1:1 with my students.

Utilize a Zoom link or connect with students via telephone.

How to operate a telephone: https://tech.msu.edu/network/telecommunications/

Implement

The above are just a few options for participation and engagement so as to mirror similar approaches utilized in your classroom. Remember to start small and stick to the tools you’re comfortable with.

Additional Help

For additional help and support, please check out other remote teaching articles on iteach.msu.edu or contact the MSU IT Service Desk at local (517) 432-6200 or toll free (844) 678-6200.

Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

This document provides an introduction to maintaining student engagement as you move to remote teaching. It outlines key steps to Plan, Modify, and Implement when making this move to optimize student learning. As with any steps you take in moving to remote teaching, it’s important to anchor your decisions in course learning objectives and to be transparent, flexible, and generous with students.

Plan

In planning how you will continue to engage students in your course, remember that interaction can occur between the student and you, the student and other students, and the student and the course materials.

Modify

When modifying in-class activities to a remote offering, you can start by cataloguing all of the ways people typically interact in your classroom. This list can then be used to identify particular digital strategies or technologies for adapting your current approach and translating your methods to an online space. For example, you might draft a table like the one below:

Interactions

Class Activity

Modify

Implement

Teacher to students:

During lecture, I ask questions to check student understanding.

Ask a poll question in a live Zoom session or D2L discussion forum whereas students respond to a prompt.

How to create a poll in Zoom:

https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/203749865-Polling-for-Webinars

How to manage D2L discussion forum:

https://documentation.brightspace.com/EN/le/discussions/learner/discussions_intro_1.htm

Student to material:

We watch and discuss a video.

Share a link with students in a variety of ways - i.e. post the link in a D2L discussion forum along with questions for response.

How to create a link in D2L: https://resources.depaul.edu/teaching-commons/teaching-guides/technology/desire2learn/tools/content/Pages/creating-links.aspx

Student to students:

I facilitate a classroom discussion and students respond to the prompt.

Create breakout rooms in a live Zoom session or a D2L discussion forum.

How to make and manage Zoom Breakout rooms: https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/206476313-Managing-Video-Breakout-Rooms

How to manage D2L discussion forum:

https://documentation.brightspace.com/EN/le/discussions/learner/discussions_intro_1.htm

Student to students:

I put students in small groups for more active discussions.

Create breakout rooms in a live Zoom session or D2L discussion forum whereas students respond to a prompt.

How to manage D2L discussion forum:

https://documentation.brightspace.com/EN/le/discussions/learner/discussions_intro_1.htm

Teacher to student:

I hold office hours to meet 1:1 with my students.

Utilize a Zoom link or connect with students via telephone.

How to operate a telephone: https://tech.msu.edu/network/telecommunications/

Implement

The above are just a few options for participation and engagement so as to mirror similar approaches utilized in your classroom. Remember to start small and stick to the tools you’re comfortable with.

Additional Help

For additional help and support, please check out other remote teaching articles on iteach.msu.edu or contact the MSU IT Service Desk at local (517) 432-6200 or toll free (844) 678-6200.

Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Authored by:

4.0 International (CC by 4.0)

Posted on: MSU Online & Remote Teaching

Remote participation quick guide

click the image above to access a PDF file of the quick guideRemote...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Oct 18, 2021