We found 1339 results that contain "womxn of color"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

ASSESSING LEARNING

Biology of Skin Color: Assignment Example

In ISB202, Spring Semester 2020, the first high-impact assessment is applying nature of science and scientific literacy concepts to a case study on the biology of skin color. The worksheet and corresponding answers are included below. The full grading rubric can be found by clicking the attachment.

Part 1: The Investigation

1. Consider the research question: “Is there a connection in the intensity of UV radiation and skin color?” What type of study did they perform to investigate this question (observational study, modeling study, or experiment)?

Modeling or observational study are acceptable answers.

2. Explain some of the key components of the study that explain your choice for question #1. Make sure to include specific components (e.g., if there is a control and experimental group, then what were they? If not, then how do you know?). Answer in 2-3 sentences.

Modeling: maps are models showing distribution of skin color and UV radiation

Observational: collected data and did not have a control and experimental group- would not make sense with this research question to do an experiment

3. Evaluate the study’s methods. For instance, what kinds of things were held constant (for example, when we compared different models of the tube activity, each model developer had access to the same materials)? What was the sample size and did it use replicates? Consider different factors that we discussed during Week 2. Evaluate the methods; do not just create a list. Answer in 3-4 sentences.

Answers will vary, such as constants being using similar tools for measuring skin color and UV radiation

4. After they created the two maps (one for UV exposure and one for skin color), what was the resulting conclusion? Make sure to consider this part of the study and not the entire video.

Correlation between skin color and UV radiation (they may make a causal statement, which is also used in the video)

Answer should be the causes of this correlation (such as folate and vitamin D)

5. Describe a general pattern in the maps (i.e., the data) that support the conclusion that you described for question #4. Then explain two specific examples that support it.

The general pattern of darker skin in areas with more UV radiation and they will need two specific examples; they might describe higher elevations also correlating with darker skin (and more UV radiation)

6. After viewing the entire video, what kinds of questions do you have? Develop one testable, scientific research question that extends the research (no just replicate it).

Answer varies but should be testable and not just ethical questions- it is fine if the question is a natural science or social science question.

Part 2: Data Analysis

7. The graph below summarizes the age at which people are diagnosed with melanoma, the most serious form of skin cancer. Consider the claims made throughout the video. Does this graph support or refute a claim in the video? Complete “a” and “b” below to answer this question.

A. Describe the relevant claim in one sentence:

Darker skin (may also mention eumelanin) is selected for to protect folate, an important vitamin for preventing birth defects; it is not selected for to prevent skin cancer

B. Do the data in the graph support or refute the claim? Explain your reasoning in 2-3 sentences.

Majority of people get skin cancer after 45 years of age, which is after reproductive years- natural selection cannot act after reproductive years because it does not affect the probability of getting genes to the next generation.

Part 3: Controversies

8. Describe one scientific controversy mentioned in the video- either current or resolved. Describe the specific evidence and define “scientific controversy” within your explanation. Answer in 3-5 sentences.

The main controversy that students may describe is why dark skin was selected for. Originally thought it was due to protect against skin cancer, which evidence does support that those with darker skin are less likely to develop skin cancer. However, new evidence suggests that it is to protect folate after it was showed to be important in preventing birth defects and can be damaged by UV radiation.

The controversy must be a scientific controversy, not an ethical one.

Part 1: The Investigation

1. Consider the research question: “Is there a connection in the intensity of UV radiation and skin color?” What type of study did they perform to investigate this question (observational study, modeling study, or experiment)?

Modeling or observational study are acceptable answers.

2. Explain some of the key components of the study that explain your choice for question #1. Make sure to include specific components (e.g., if there is a control and experimental group, then what were they? If not, then how do you know?). Answer in 2-3 sentences.

Modeling: maps are models showing distribution of skin color and UV radiation

Observational: collected data and did not have a control and experimental group- would not make sense with this research question to do an experiment

3. Evaluate the study’s methods. For instance, what kinds of things were held constant (for example, when we compared different models of the tube activity, each model developer had access to the same materials)? What was the sample size and did it use replicates? Consider different factors that we discussed during Week 2. Evaluate the methods; do not just create a list. Answer in 3-4 sentences.

Answers will vary, such as constants being using similar tools for measuring skin color and UV radiation

4. After they created the two maps (one for UV exposure and one for skin color), what was the resulting conclusion? Make sure to consider this part of the study and not the entire video.

Correlation between skin color and UV radiation (they may make a causal statement, which is also used in the video)

Answer should be the causes of this correlation (such as folate and vitamin D)

5. Describe a general pattern in the maps (i.e., the data) that support the conclusion that you described for question #4. Then explain two specific examples that support it.

The general pattern of darker skin in areas with more UV radiation and they will need two specific examples; they might describe higher elevations also correlating with darker skin (and more UV radiation)

6. After viewing the entire video, what kinds of questions do you have? Develop one testable, scientific research question that extends the research (no just replicate it).

Answer varies but should be testable and not just ethical questions- it is fine if the question is a natural science or social science question.

Part 2: Data Analysis

7. The graph below summarizes the age at which people are diagnosed with melanoma, the most serious form of skin cancer. Consider the claims made throughout the video. Does this graph support or refute a claim in the video? Complete “a” and “b” below to answer this question.

A. Describe the relevant claim in one sentence:

Darker skin (may also mention eumelanin) is selected for to protect folate, an important vitamin for preventing birth defects; it is not selected for to prevent skin cancer

B. Do the data in the graph support or refute the claim? Explain your reasoning in 2-3 sentences.

Majority of people get skin cancer after 45 years of age, which is after reproductive years- natural selection cannot act after reproductive years because it does not affect the probability of getting genes to the next generation.

Part 3: Controversies

8. Describe one scientific controversy mentioned in the video- either current or resolved. Describe the specific evidence and define “scientific controversy” within your explanation. Answer in 3-5 sentences.

The main controversy that students may describe is why dark skin was selected for. Originally thought it was due to protect against skin cancer, which evidence does support that those with darker skin are less likely to develop skin cancer. However, new evidence suggests that it is to protect folate after it was showed to be important in preventing birth defects and can be damaged by UV radiation.

The controversy must be a scientific controversy, not an ethical one.

Authored by:

Andrea Bierema

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Biology of Skin Color: Assignment Example

In ISB202, Spring Semester 2020, the first high-impact assessment i...

Authored by:

ASSESSING LEARNING

Monday, Oct 12, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

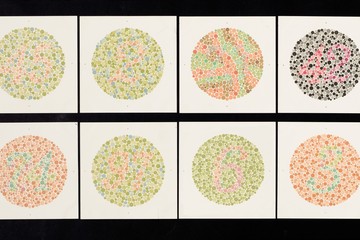

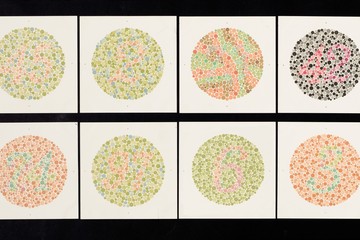

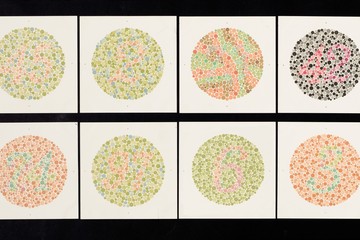

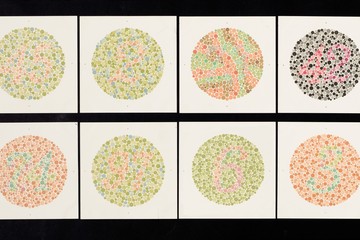

Accessibility: Color Contrast Resources

Curious if the color in a graphic or text has enough contrast to be accessible to those with low vision or color blindness? If so, there are a few free online resources to help you out.The WCAG Color Contrast Checker, which you can use directly on their website or bookmark it, and the TPGI Colour Contrast Analyzer, which can be downloaded, are fairly easy to use. For either one, just use the "eyedropper" tool to grab a color from a document, webpage, etc. and it will provide you with the color contrast ratio and "pass" or "fail" results. Additionally, WAVE is a web accessibility evaluation tool in which you enter the website that you are interested in testing and it will locate any color contrast errors, in addition to other accessibility measures.If you have full color vision and would like to see for yourself how a website looks to someone who is colorblind, then try Coblis or Let's Get Color Blind. Let's Get Color Blind is a browser extension for Chrome or Firefox. It simulates reduced sensitivity to green, red, or blue for an entire webpage. If you are interested in testing a specific image, then try Coblis (The Color Blindness Simulator), which simulates reduced sensitivity and blindness for green, red, or blue as well as full-color blindness. I discovered these resources from Guide to Digital Accessibility (Ed. Mancilla & Frey, 2023, ISBN-13: 978-1-64267-453-8). Learn more about color contrast from MSU's Digital Accessibility.Feature Image: "Eight Ishihara Charts for Testing Colour Blindness" by Fae licensed under CC BY 4.0 DEED.

Authored by:

Andrea Bierema

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Accessibility: Color Contrast Resources

Curious if the color in a graphic or text has enough contrast to be...

Authored by:

Thursday, Oct 5, 2023

Posted on: #iteachmsu

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Application of Studio Culture in University Schools of Music

A central part of the student experience as a music major in a school or department of music is the studio. Studios are essentially a home-away-from-home for students and is where some of the most fruitful learning and social opportunities can occur. One could equate studios with working in a research lab in the sciences. With this in mind, the culture and atmosphere of studios and how studios interact with others are central to the culture and effectiveness of the larger school or department.

Music students often enter higher education with a fairly high standard of what classroom culture looks like. Ensemble music courses that music students likely took in high school, such as band, choir, and orchestra, foster a high-level classroom culture and community by the nature of the activity. This creates an expectation that music education, at any level and in any situation, will have that same sort of cooperation and community. The ensemble nature of large group instruction fosters a strong sense of shared identity and a culture that defines everything from day-to-day classroom routine to learner outcomes. University music programs (departments, schools, colleges, or conservatories) are structured in order to teach, perform, and experience music in a variety of ways. While the large ensemble (band, choir, orchestra, opera, etc) is a significant part of the school – and perhaps the most visible to the general public – learning also occurs in traditional classrooms and labs where foundational knowledge such as music theory, music history, music technology, music education, and aural skills are taught.

The core of a college or university music program or conservatory, however, is the studio. Each area of performance is organized by a studio and led by an applied teacher. At Michigan State, for example, within the College of Music there are areas of study for composition, conducting, jazz, voice, brass, woodwinds, percussion, strings and piano. Each of these areas consist of studios led by artist-teachers. The woodwind area, for example, consists of studios for flute, oboe, bassoon, clarinet, and saxophone and an applied teacher for each of those studios. For many students, especially graduate students, they elect to come to certain school to specifically study with that applied teacher. While students participate in ensembles, take classroom courses, and are educated through several avenues, the studio teacher is their major professor and advisor, and typically has the most contact time and influence on that student.

Studios in schools of music, however, can sometimes seem isolated from each other. This can occur for several valid reasons and not the fault of any one student or faculty member. Unlike large ensembles, where cooperation and a mutual understanding of each member’s role is an essential aspect to music-making, studios often focus on specific pedagogical goals based around the expertise of the individual teacher. And studios can have very specific ideas of what they want their “sound” or approach to playing to be. This can sometimes lead to issues in understanding the priorities of other studios and creates a divide in the school where philosophical conflicts may arise between teaching goals and strategies. This conflict is not the fault of the teachers, and usually is not caused or perpetuated by faculty. Faculty typically understand this dynamic because they have a vision of what they want their studio to be and each understands that other faculty may have different goals. While it is possible they may disagree with certain choices in other studios, each teacher comes to the job with their own unique set of skills and priorities. As long as students are choosing to come to the school, being successful within the school, and being productive musicians contributing to the field after school – the teacher’s work is often judged as a success.

Sometimes the breakdown occurs with how students perceive the work of other studios. Learning does not occur in a vacuum. While the studio is often the hub of the learning, much of a student’s time is spent in performing ensembles. It is in cooperative spaces like this that the breakdown can come to a head. Teachers have different priorities and students have different goals. When one person’s goal rubs against another’s goal, conflict can arise. Each instrument has inherent attributes that make them unique and different from others – and therefore difficult to compare. Oboist have to learn to make reeds, tubists may also need to learn euphonium, violinists sometimes also learn viola, trombonists may need to learn to read tenor clef, and saxophonists are always stretching their skills with extended performance techniques. Every instrument has its own challenge, and the fundamental knowledge necessary before moving onto the next step of learning varies considerably between all of them. Furthermore, every student focuses their study in order to be competitive for differing jobs following graduation. Students seeking college teaching positions may need to study theory pedagogy in addition to learning to play their instrument well, while other students may focus on obtaining an orchestral playing position – which has very specific skills you need to perfect. These are facts often overlooked in the frustration that occurs when goals do not align in rehearsal. Understanding where students are coming from and the different paths and pacing each needs to take to meet different goals is something that my colleague and fellow DMA student Evan Harger calls “vocational empathy.” These unique and varied paths sometimes create a flawed perception of what really is progress.

Large ensembles are led by conductors who guide the direction, philosophy, and culture of the learning environment. Conductors navigate through the web of individual philosophies of each studio and performer to create an ensemble experience that proves to be a successful composite of a variety of pedagogical approaches. In addition to large ensembles, another significant performance opportunity for students are chamber ensembles. In these small groups, students have more autonomy and sometimes conflict can arise between contrasting ideologies and rehearsal priorities. It is not uncommon in chamber ensembles, where there is little faculty input and the music-making is purely student-led, to have differing approaches to the ensemble experience. Everything from rehearsal strategies and what components of the music needs addressing to ideas about performance practice and interpretation can differ and pose potential conflicts. While these are issues and topics to consider in any ensemble opportunity, even in the professional ranks, academia sometimes creates environments where students develop tunnel vision to their own learning biases and objectives.

In order to create healthier ensemble experiences, understanding and developing positive studio culture allows students to not only feel comfortable and foster deeper learning within their studios but also allows for more meaningful cross-studio learning. By allowing students the opportunity to understand the focus and approaches of other studios, students are able to more easily collaborate with those who might approach the same musical issue from an entirely different angle. This awareness of multiple ways to view the same idea, or even being presented with new ideas entirely, creates an environment where cooperation happens more deeply, naturally, and genuinely. This allows for the development of stronger ensemble skills in rehearsal and contributes to more authentic performances. Additionally, this awareness of why certain studios focus on particular aspects allows for students to be better colleagues in future professional, academic, and business environments. We approach conflict and problem-solving through a lens developed in rehearsal and through conversations in the studios. For future teachers and professors, we have a deeper toolbox of instructional strategies to pick from to use in our own future classrooms and studios. This shared knowledge combats the issue of tunnel-vision-learning that limits our capacity for performance as well as the capacity for understanding, cooperation, and growth.

An awareness of vocational empathy creates an avenue where students can share what they value in their studios and as individual learners in order to better understand the values of others. To be a successful 21st century musician, a wide variety of skills are necessary. But what we focus on, the degree to which one does, and the end goal of that study is something that cannot be compared. Richard Floyd, a noted music educator and State Director of Music Emeritus for Texas, calls this space where students are engaged and seeking to learn in a variety of ways a “happy workshop.” And within this workshop, there are a lot of people doing a lot of different jobs in a lot of different ways that all work together to teach and learn from each other. This healthy culture knocks on the door of Paulo Freire’s view that teaching and learning are interchangeable and that the student and teacher do both.

Through working with the Graduate School as a Leadership Development Fellow, I was able to dig into what defines a successful studio culture and how we can best connect these cultures to foster a positive and productive learning environment within the entire College of Music. This past year served as essentially a fact-finding year: defining, through research and student voice, what a productive studio culture looks like and where conflict can arise and how to work through conflict. Higher education music rarely defines this awareness and implications of how studio culture effects an entire school. By and large, music studios look very similar today as they did twenty-five or even fifty years ago. Generally, many teachers still teach the way they were taught. MSU is fortunate that we have many innovative and progressive educators, but the notion of still teaching as we were taught is all too common in academia.

To define best practices in studio culture and to compare the music field to other fields, I looked for defining qualities in classroom culture in higher education. Some of the most relevant ideas of studio culture came from architecture. The American Institute of Architecture Students In-StudioBlog travels to architecture studios across the country, asking many of the same questions that we are asking in the College of Music.

Describe your studio culture.

Give one tip that helped you succeed in studio.

What motivated you to work hard in studio?

What aspect of your studio experience do you think will help you get a job?

What can professors do to create a helpful and supportive studio culture?

What should a high school student understand about studio at my university?

What can the College do to help improve your studio experience?

What would be your ideal studio care package?

I love my studio because….

Schools of architecture have a fairly well-thought out approach to what culture looks like in their studios. The Princeton University School of Architecture has a detailed “Studio Culture Policy” which aligns well with similar concerns in a music studio. From speaking with students in the College of Music, topics raised in these architecture policies are similar to concerns shared here – and I would venture to say any classroom can benefit from tough conversations about culture and productive, cooperative learning environments. These same conversations can apply to other close learning environments in the arts such as dance studios and theater programs; but they are equally relevant and impactful in scientific research labs.

Through the Graduate School’s Leadership Development Fellowship, we’ve created a forum where music students can share what makes their studio’s unique, what brought them to study at MSU, and also concerns or suggestions they have to improve our College. In an open environment where all can share ideas, we not only create a space where cooperation and understanding are built, but also allow ourselves to deepen our own toolbox that can be used in the professional world and in future classrooms and studios. An initial meeting of this forum quickly veered away from talking about our own studios and personal interests, but to larger questions in the discipline of music: ideas about music and its role in global citizenship, entrepreneurial skills in the performing arts, repertoire selection and variety, and diversity and representation. These are important topics beyond the scope of studio culture, but agreement exists that each studio can make a significant difference in these areas. Studios can be the start of grassroot change in tackling bigger issues in music and music education. When we come together to talk about these significant issues and how each studio confronts them, we are making positive change – not only in our studios and the College of Music – but in music and music-making at large. This year we just barely scratched the surface of the impact that we can have on understanding and developing the culture in our studios. From the initial research and student conversations, it is apparent that these ideas make a meaningful difference on our learning environment in real ways that will have impacts far beyond the walls of the College of Music.

Music students often enter higher education with a fairly high standard of what classroom culture looks like. Ensemble music courses that music students likely took in high school, such as band, choir, and orchestra, foster a high-level classroom culture and community by the nature of the activity. This creates an expectation that music education, at any level and in any situation, will have that same sort of cooperation and community. The ensemble nature of large group instruction fosters a strong sense of shared identity and a culture that defines everything from day-to-day classroom routine to learner outcomes. University music programs (departments, schools, colleges, or conservatories) are structured in order to teach, perform, and experience music in a variety of ways. While the large ensemble (band, choir, orchestra, opera, etc) is a significant part of the school – and perhaps the most visible to the general public – learning also occurs in traditional classrooms and labs where foundational knowledge such as music theory, music history, music technology, music education, and aural skills are taught.

The core of a college or university music program or conservatory, however, is the studio. Each area of performance is organized by a studio and led by an applied teacher. At Michigan State, for example, within the College of Music there are areas of study for composition, conducting, jazz, voice, brass, woodwinds, percussion, strings and piano. Each of these areas consist of studios led by artist-teachers. The woodwind area, for example, consists of studios for flute, oboe, bassoon, clarinet, and saxophone and an applied teacher for each of those studios. For many students, especially graduate students, they elect to come to certain school to specifically study with that applied teacher. While students participate in ensembles, take classroom courses, and are educated through several avenues, the studio teacher is their major professor and advisor, and typically has the most contact time and influence on that student.

Studios in schools of music, however, can sometimes seem isolated from each other. This can occur for several valid reasons and not the fault of any one student or faculty member. Unlike large ensembles, where cooperation and a mutual understanding of each member’s role is an essential aspect to music-making, studios often focus on specific pedagogical goals based around the expertise of the individual teacher. And studios can have very specific ideas of what they want their “sound” or approach to playing to be. This can sometimes lead to issues in understanding the priorities of other studios and creates a divide in the school where philosophical conflicts may arise between teaching goals and strategies. This conflict is not the fault of the teachers, and usually is not caused or perpetuated by faculty. Faculty typically understand this dynamic because they have a vision of what they want their studio to be and each understands that other faculty may have different goals. While it is possible they may disagree with certain choices in other studios, each teacher comes to the job with their own unique set of skills and priorities. As long as students are choosing to come to the school, being successful within the school, and being productive musicians contributing to the field after school – the teacher’s work is often judged as a success.

Sometimes the breakdown occurs with how students perceive the work of other studios. Learning does not occur in a vacuum. While the studio is often the hub of the learning, much of a student’s time is spent in performing ensembles. It is in cooperative spaces like this that the breakdown can come to a head. Teachers have different priorities and students have different goals. When one person’s goal rubs against another’s goal, conflict can arise. Each instrument has inherent attributes that make them unique and different from others – and therefore difficult to compare. Oboist have to learn to make reeds, tubists may also need to learn euphonium, violinists sometimes also learn viola, trombonists may need to learn to read tenor clef, and saxophonists are always stretching their skills with extended performance techniques. Every instrument has its own challenge, and the fundamental knowledge necessary before moving onto the next step of learning varies considerably between all of them. Furthermore, every student focuses their study in order to be competitive for differing jobs following graduation. Students seeking college teaching positions may need to study theory pedagogy in addition to learning to play their instrument well, while other students may focus on obtaining an orchestral playing position – which has very specific skills you need to perfect. These are facts often overlooked in the frustration that occurs when goals do not align in rehearsal. Understanding where students are coming from and the different paths and pacing each needs to take to meet different goals is something that my colleague and fellow DMA student Evan Harger calls “vocational empathy.” These unique and varied paths sometimes create a flawed perception of what really is progress.

Large ensembles are led by conductors who guide the direction, philosophy, and culture of the learning environment. Conductors navigate through the web of individual philosophies of each studio and performer to create an ensemble experience that proves to be a successful composite of a variety of pedagogical approaches. In addition to large ensembles, another significant performance opportunity for students are chamber ensembles. In these small groups, students have more autonomy and sometimes conflict can arise between contrasting ideologies and rehearsal priorities. It is not uncommon in chamber ensembles, where there is little faculty input and the music-making is purely student-led, to have differing approaches to the ensemble experience. Everything from rehearsal strategies and what components of the music needs addressing to ideas about performance practice and interpretation can differ and pose potential conflicts. While these are issues and topics to consider in any ensemble opportunity, even in the professional ranks, academia sometimes creates environments where students develop tunnel vision to their own learning biases and objectives.

In order to create healthier ensemble experiences, understanding and developing positive studio culture allows students to not only feel comfortable and foster deeper learning within their studios but also allows for more meaningful cross-studio learning. By allowing students the opportunity to understand the focus and approaches of other studios, students are able to more easily collaborate with those who might approach the same musical issue from an entirely different angle. This awareness of multiple ways to view the same idea, or even being presented with new ideas entirely, creates an environment where cooperation happens more deeply, naturally, and genuinely. This allows for the development of stronger ensemble skills in rehearsal and contributes to more authentic performances. Additionally, this awareness of why certain studios focus on particular aspects allows for students to be better colleagues in future professional, academic, and business environments. We approach conflict and problem-solving through a lens developed in rehearsal and through conversations in the studios. For future teachers and professors, we have a deeper toolbox of instructional strategies to pick from to use in our own future classrooms and studios. This shared knowledge combats the issue of tunnel-vision-learning that limits our capacity for performance as well as the capacity for understanding, cooperation, and growth.

An awareness of vocational empathy creates an avenue where students can share what they value in their studios and as individual learners in order to better understand the values of others. To be a successful 21st century musician, a wide variety of skills are necessary. But what we focus on, the degree to which one does, and the end goal of that study is something that cannot be compared. Richard Floyd, a noted music educator and State Director of Music Emeritus for Texas, calls this space where students are engaged and seeking to learn in a variety of ways a “happy workshop.” And within this workshop, there are a lot of people doing a lot of different jobs in a lot of different ways that all work together to teach and learn from each other. This healthy culture knocks on the door of Paulo Freire’s view that teaching and learning are interchangeable and that the student and teacher do both.

Through working with the Graduate School as a Leadership Development Fellow, I was able to dig into what defines a successful studio culture and how we can best connect these cultures to foster a positive and productive learning environment within the entire College of Music. This past year served as essentially a fact-finding year: defining, through research and student voice, what a productive studio culture looks like and where conflict can arise and how to work through conflict. Higher education music rarely defines this awareness and implications of how studio culture effects an entire school. By and large, music studios look very similar today as they did twenty-five or even fifty years ago. Generally, many teachers still teach the way they were taught. MSU is fortunate that we have many innovative and progressive educators, but the notion of still teaching as we were taught is all too common in academia.

To define best practices in studio culture and to compare the music field to other fields, I looked for defining qualities in classroom culture in higher education. Some of the most relevant ideas of studio culture came from architecture. The American Institute of Architecture Students In-StudioBlog travels to architecture studios across the country, asking many of the same questions that we are asking in the College of Music.

Describe your studio culture.

Give one tip that helped you succeed in studio.

What motivated you to work hard in studio?

What aspect of your studio experience do you think will help you get a job?

What can professors do to create a helpful and supportive studio culture?

What should a high school student understand about studio at my university?

What can the College do to help improve your studio experience?

What would be your ideal studio care package?

I love my studio because….

Schools of architecture have a fairly well-thought out approach to what culture looks like in their studios. The Princeton University School of Architecture has a detailed “Studio Culture Policy” which aligns well with similar concerns in a music studio. From speaking with students in the College of Music, topics raised in these architecture policies are similar to concerns shared here – and I would venture to say any classroom can benefit from tough conversations about culture and productive, cooperative learning environments. These same conversations can apply to other close learning environments in the arts such as dance studios and theater programs; but they are equally relevant and impactful in scientific research labs.

Through the Graduate School’s Leadership Development Fellowship, we’ve created a forum where music students can share what makes their studio’s unique, what brought them to study at MSU, and also concerns or suggestions they have to improve our College. In an open environment where all can share ideas, we not only create a space where cooperation and understanding are built, but also allow ourselves to deepen our own toolbox that can be used in the professional world and in future classrooms and studios. An initial meeting of this forum quickly veered away from talking about our own studios and personal interests, but to larger questions in the discipline of music: ideas about music and its role in global citizenship, entrepreneurial skills in the performing arts, repertoire selection and variety, and diversity and representation. These are important topics beyond the scope of studio culture, but agreement exists that each studio can make a significant difference in these areas. Studios can be the start of grassroot change in tackling bigger issues in music and music education. When we come together to talk about these significant issues and how each studio confronts them, we are making positive change – not only in our studios and the College of Music – but in music and music-making at large. This year we just barely scratched the surface of the impact that we can have on understanding and developing the culture in our studios. From the initial research and student conversations, it is apparent that these ideas make a meaningful difference on our learning environment in real ways that will have impacts far beyond the walls of the College of Music.

Authored by:

Hunter Kopczynski

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Application of Studio Culture in University Schools of Music

A central part of the student experience as a music major in a scho...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Wednesday, May 20, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Community of Inquiry

The Community of Inquiry framework proposed by Garrison, Anderson, and Archern (2000) identifies three dimensions to support a social constructivist model of learning. Research suggests that building these three dimensions into your course will help to support the learning experience for your students.

Cognitive Presence

Cognitive presence refers to the way your students might construct meaning in your course. This happens when they have the chance to be curious, explore, and have an "ah-ha" moment. You'll see this when they're able to connect and apply new ideas from the course. The important steps you'll need to take to support cognitive presence are to carefully select content for your course and support discourse. You can help to build this into your course by providing multiple opportunities for students to explore and engage with material that will help them to understand the big ideas. You can accomplish this in your course by providing different options for engaging with the content, such as reading texts, watching videos, and completing learning activities and various assessments.

Social Presence

Social presence refers to the way your students might present themselves to the class. This happens when students have opportunities to openly communicate in class, and are free to express emotions in a risk-free environment. To encourage this, you should support the discourse and set the climate for discussion. You can support this by providing opportunities for interaction and collaboration amongst students and by modeling the kinds of behaviors they should follow. You can accomplish this by asking students to introduce themselves, either in a live zoom meeting or on the course discussion board. Set parameters for students to engage in discussion in both the asynchronous and synchronous environments. For example, in a synchronous zoom meeting you might direct students to post in the chat to answer a question and set breakout rooms for students to engage with their peers. Or, you might direct students to complete an assignment in a small group, and direct them to use an asynchronous discussion board to chat and plan their assignment.

Teaching Presence

Teaching presence refers to your structure and process, including how you will provide direct instruction to your students and build understanding. This means selecting the content, identifying the topics for discussion, and keeping the discussion focused on those topics. It will also help if you set the social climate and provide clear instructions for how students should engage with and respond to these discussions. You can easily accomplish this with discussion forums related to course topics, with targeted discussion questions in your online course. What are some other ways you might accomplish this?

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T, & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87–105

"Community of Inquiry Model" by jrhode is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Cognitive Presence

Cognitive presence refers to the way your students might construct meaning in your course. This happens when they have the chance to be curious, explore, and have an "ah-ha" moment. You'll see this when they're able to connect and apply new ideas from the course. The important steps you'll need to take to support cognitive presence are to carefully select content for your course and support discourse. You can help to build this into your course by providing multiple opportunities for students to explore and engage with material that will help them to understand the big ideas. You can accomplish this in your course by providing different options for engaging with the content, such as reading texts, watching videos, and completing learning activities and various assessments.

Social Presence

Social presence refers to the way your students might present themselves to the class. This happens when students have opportunities to openly communicate in class, and are free to express emotions in a risk-free environment. To encourage this, you should support the discourse and set the climate for discussion. You can support this by providing opportunities for interaction and collaboration amongst students and by modeling the kinds of behaviors they should follow. You can accomplish this by asking students to introduce themselves, either in a live zoom meeting or on the course discussion board. Set parameters for students to engage in discussion in both the asynchronous and synchronous environments. For example, in a synchronous zoom meeting you might direct students to post in the chat to answer a question and set breakout rooms for students to engage with their peers. Or, you might direct students to complete an assignment in a small group, and direct them to use an asynchronous discussion board to chat and plan their assignment.

Teaching Presence

Teaching presence refers to your structure and process, including how you will provide direct instruction to your students and build understanding. This means selecting the content, identifying the topics for discussion, and keeping the discussion focused on those topics. It will also help if you set the social climate and provide clear instructions for how students should engage with and respond to these discussions. You can easily accomplish this with discussion forums related to course topics, with targeted discussion questions in your online course. What are some other ways you might accomplish this?

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T, & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87–105

"Community of Inquiry Model" by jrhode is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Authored by:

Breana Yaklin

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Community of Inquiry

The Community of Inquiry framework proposed by Garrison, Anderson, ...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Wednesday, Sep 9, 2020

Posted on: PREP Matrix

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Elements of Style

Bartelby.com provides the full-text of William Strunk Jr.'s guide to style, grammar, and composition: The Elements of Style.

Posted by:

Admin

Posted on: PREP Matrix

Elements of Style

Bartelby.com provides the full-text of William Strunk Jr.'s guide t...

Posted by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Thursday, Aug 29, 2019

Posted on: The MSU Graduate Leadership Institute

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Surveying the Landscape of the College of SocSci Grad Student Programs

As the first Social Science Fellow, Jacob’s project focused on surveying the landscape of the College of Social Science in order to gather information on departmental procedures, college structure, and identify possible intervention points in which to enhance the graduate student experience. This included creating an organizational chart, analyzing results from a graduate student survey, and developing a database on departments, graduate programs, and GSOs in the College of Social Science.

Authored by:

Jack Bradburn

Posted on: The MSU Graduate Leadership Institute

Surveying the Landscape of the College of SocSci Grad Student Programs

As the first Social Science Fellow, Jacob’s project focused on surv...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Monday, Apr 19, 2021

Posted on: #iteachmsu

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Taking Care of Yourself in Times of Uncertainty - February 2024 Recording

We can be creatures of habit. Things that are expected and planned allow us to feel more in control of our lives and our time. With all the uncertainty in the world, from the unstable financial markets to the heightened political tensions, we are likely feeling the stress of uncertainty. This presentation will address best practices for self-care.

Hosted by Jaimie Hutchison, Director of MSU's Work Life Office, this workshop is for anyone that is looking for self-care practices. Upon completion of this learning experience participants will be able to:

Know different methods for taking care of ourselves during times of uncertainty

Understand how stress of uncertainty impacts us and common reactions

Learn different ways to engage in self-care

Hosted by Jaimie Hutchison, Director of MSU's Work Life Office, this workshop is for anyone that is looking for self-care practices. Upon completion of this learning experience participants will be able to:

Know different methods for taking care of ourselves during times of uncertainty

Understand how stress of uncertainty impacts us and common reactions

Learn different ways to engage in self-care

Authored by:

Katie Peterson

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Taking Care of Yourself in Times of Uncertainty - February 2024 Recording

We can be creatures of habit. Things that are expected and planned ...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Thursday, Feb 8, 2024

Posted on: #iteachmsu

JUSTICE AND BELONGING

Office of Institutional Equity

If a student discloses that they have experienced discrimination or harassment, you must refer them to the Office of Institutional Equity. The Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) reviews concerns related to discrimination and harassment based on age, color, gender, gender identity, disability status, height, marital status, national origin, political persuasion, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, veteran status and weight under the University's Anti-Discrimination Policy (ADP) and concerns of sexual harassment, sexual assault, stalking, dating violence, domestic violence, and other forms of sexual misconduct under the Relationship Violence and Sexual Misconduct and Title IX (RVSM) Policy.

A student can file a report here.

Confidential reporting for students

There are a number of resources on campus that can provide a confidential space where students can explore their options, talk about what happened, and obtain support services. Individuals often find it difficult to speak about what happened. Talking with someone once, or receiving ongoing support, can aid in recovery and assist with safety planning. If students access these services, they will be directed to other needed resources. These private and confidential resources are available at no cost. These services are not required to report incidents to the Office of Institutional Equity or campus police.

A student can access confidential resources here.

Mandatory reporting for faculty and staff

All University “responsible employees” and volunteers who are not otherwise exempted by this policy and/or applicable law must promptly report incidents of relationship violence, sexual misconduct, stalking, and retaliation that they observe or learn about in their professional capacity or in the context of their work and that involve a member of the University community or which occurred at a University-sponsored event or on University property. Please review the University Reporting Protocol.

A student can file a report here.

Confidential reporting for students

There are a number of resources on campus that can provide a confidential space where students can explore their options, talk about what happened, and obtain support services. Individuals often find it difficult to speak about what happened. Talking with someone once, or receiving ongoing support, can aid in recovery and assist with safety planning. If students access these services, they will be directed to other needed resources. These private and confidential resources are available at no cost. These services are not required to report incidents to the Office of Institutional Equity or campus police.

A student can access confidential resources here.

Mandatory reporting for faculty and staff

All University “responsible employees” and volunteers who are not otherwise exempted by this policy and/or applicable law must promptly report incidents of relationship violence, sexual misconduct, stalking, and retaliation that they observe or learn about in their professional capacity or in the context of their work and that involve a member of the University community or which occurred at a University-sponsored event or on University property. Please review the University Reporting Protocol.

Posted by:

Kelly Mazurkiewicz

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Office of Institutional Equity

If a student discloses that they have experienced discrim...

Posted by:

JUSTICE AND BELONGING

Tuesday, Jul 30, 2024