We found 320 results that contain "classroom observation"

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Etiquette for Peer-Educator Learning-Experience Sessions

Thinking about how to improve your educator practice, tapping in to expertise on campus, or engaging with high-impact peers can feel intimidating. Here are a few etiquette tips to accompany Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide and Protocol.

Remember, peer-educator dialogues can be initiated for multiple reasons including: an instructor-educator looking for peer-educator feedback on a learning session observation, OR a peer-educator looking to observe a peer-educator employ a practice they'd like to incorporate/improve

Regardless, avoid engaging in a learning-expereince as a peer-educator during the first two or three weeks of a semester.

Before going to observe the class, check with the instructor-educator to see if they would like to meet with you in advance. It helps to find out in advance about the class you will be engaging with— what the course is designed to do, what level the students are at, what the teacher is planning to do in the specific class to be observed and why. This could help you to make more sense of what it is that goes on in the learning-expereince.

note: if you cannot meet to have this conversation due to the complex nature of schedules, it is recommended that you asynchronously ammend the Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide to ensure the engagement meets goals all around.

Double-check with the instructor-educator prior to the engagement on:

where you sit in the classroom. Many educators may not care where you sit, as long as it doesn’t interfere with instruction, but some may have preferences.

If you didn’t have a chance to meet prior to the observation, ask the instructor-educator when you arrive.

whether or not it’s all right to move around from group to group during group-work activities.

whether or not you are going to participate in activities or just observe. (Generally speaking, it’s preferable not to participate while doing an observation. When the purpose is to observe instructor-educator, it makes more sense to focus your attention on that task.)

Arrive on time, or early — arriving late is always an interruption. And stay throughout the entire class period. Getting up and leaving early is also an interruption.

No matter how non-threatening and cooperative the peer-educator may be, learning-session observations are a necessary imposition (but an imposition nonetheless). As peer-educators, it’s good to keep this in mind when observing and let it guide your actions.

Also keep in mind that the observation should be a positive experience for both the peer-educator and the instructor-educator. Ideally, both educators will learn something as a result of the observation.

When the learning-experience ends, thank the instructor-educator (and, if possible, the learners) for inviting/allowing you to observe them.

Debriefing should be done as soon as is feasible after the class session, while the events are still fresh in mind.

In general, if you have concerns, you can ask questions to clarify some things that happened in the class

“I’m very interested in learning more about XXXX. Could you explain why you set up the XXXX activity the way you did?”

“How do you think it went?”

The instructor-educator may have planned something that they thought was going to work marvelously, but didn’t... Or, if they noticed that it didn’t work, they may ask you for your ideas about how it could have been more effective.

Keep in mind how you would feel if you were the one being observed, and what kinds of feedback would be most useful to you.

If you notice a number of areas where the learning-expereince could be enhanced, try not to overwhelm the instructor-educator with suggestions; limit your feedback to the areas where they are seeking feedback, or perhaps those points that seem most immediately important to address.

Share your notes and onservations from the Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide and Protocol with ONLY the instructor-educator. This practice is purely a itterative dialogue amongst peers, NOT an evaluative report to be shared with administratiors. What an instructor-educator chooses to do with your notes is up to them.

This list has been adapted from the University of Hawai'i, English Language Institute "Guidelines and Etiquette for Observers".Photo by Dom Fou on Unsplash

Remember, peer-educator dialogues can be initiated for multiple reasons including: an instructor-educator looking for peer-educator feedback on a learning session observation, OR a peer-educator looking to observe a peer-educator employ a practice they'd like to incorporate/improve

Regardless, avoid engaging in a learning-expereince as a peer-educator during the first two or three weeks of a semester.

Before going to observe the class, check with the instructor-educator to see if they would like to meet with you in advance. It helps to find out in advance about the class you will be engaging with— what the course is designed to do, what level the students are at, what the teacher is planning to do in the specific class to be observed and why. This could help you to make more sense of what it is that goes on in the learning-expereince.

note: if you cannot meet to have this conversation due to the complex nature of schedules, it is recommended that you asynchronously ammend the Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide to ensure the engagement meets goals all around.

Double-check with the instructor-educator prior to the engagement on:

where you sit in the classroom. Many educators may not care where you sit, as long as it doesn’t interfere with instruction, but some may have preferences.

If you didn’t have a chance to meet prior to the observation, ask the instructor-educator when you arrive.

whether or not it’s all right to move around from group to group during group-work activities.

whether or not you are going to participate in activities or just observe. (Generally speaking, it’s preferable not to participate while doing an observation. When the purpose is to observe instructor-educator, it makes more sense to focus your attention on that task.)

Arrive on time, or early — arriving late is always an interruption. And stay throughout the entire class period. Getting up and leaving early is also an interruption.

No matter how non-threatening and cooperative the peer-educator may be, learning-session observations are a necessary imposition (but an imposition nonetheless). As peer-educators, it’s good to keep this in mind when observing and let it guide your actions.

Also keep in mind that the observation should be a positive experience for both the peer-educator and the instructor-educator. Ideally, both educators will learn something as a result of the observation.

When the learning-experience ends, thank the instructor-educator (and, if possible, the learners) for inviting/allowing you to observe them.

Debriefing should be done as soon as is feasible after the class session, while the events are still fresh in mind.

In general, if you have concerns, you can ask questions to clarify some things that happened in the class

“I’m very interested in learning more about XXXX. Could you explain why you set up the XXXX activity the way you did?”

“How do you think it went?”

The instructor-educator may have planned something that they thought was going to work marvelously, but didn’t... Or, if they noticed that it didn’t work, they may ask you for your ideas about how it could have been more effective.

Keep in mind how you would feel if you were the one being observed, and what kinds of feedback would be most useful to you.

If you notice a number of areas where the learning-expereince could be enhanced, try not to overwhelm the instructor-educator with suggestions; limit your feedback to the areas where they are seeking feedback, or perhaps those points that seem most immediately important to address.

Share your notes and onservations from the Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide and Protocol with ONLY the instructor-educator. This practice is purely a itterative dialogue amongst peers, NOT an evaluative report to be shared with administratiors. What an instructor-educator chooses to do with your notes is up to them.

This list has been adapted from the University of Hawai'i, English Language Institute "Guidelines and Etiquette for Observers".Photo by Dom Fou on Unsplash

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Etiquette for Peer-Educator Learning-Experience Sessions

Thinking about how to improve your educator practice, tapping in to...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Oct 3, 2022

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide

Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide[*]

This is a "Checklist" guide, not a scaled rating or evaluation form. This guide is intended to be used as a tool to enable educators… “who teach, supervise and/or support students’ learning to gain feedback from one or more colleagues as part of the process of reflecting on their own practices” (University of Exeter). It asks peer-educators to indicate the presence of teaching activities/behaviors already established as indicative of high-quality teaching. Individual educators, units, departments, etc. can determine which of the items in the categorized lists below reflect their priorities; a targeted set of items per list will make the guide easier for educators to use.

Date:Time: Instructor-educator name:Course #:Course Title:Modality:No. Students:Peer-Educator name:

Peer-educator instructions: Indicate with a check (√) the presence of the following actions and behaviors that indicate high quality teaching. Leave blank items you do not observe. Use N/A if an item is not relevant for this experience or the instructor’s teaching style.

Variety and Pacing of Instruction

The instructor-educator:

uses more than one form of instruction

pauses after asking questions

accepts students’ responses

draws non-participating students into activities/discussions

prevents specific students from dominating activities/discussions

helps students extend their responses

guides the direction of discussion

mediates conflict or differences of opinion

demonstrates active listening

provides explicit directions for active learning tasks (e.g. rationale, duration, product)

allows sufficient time to complete tasks such as group work

specifies how learning tasks will be evaluated (if at all)

provides opportunities and time for students to practice

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Organization

The instructor-educator :

arrives on time

relates this and previous class(es), or provides students with an opportunity to do so

provides class goals or objectives for the class session

provides an outline or organization for the class session

knows how to use the educational technology needed for the class

locates class materials as needed

makes transitional statements between class segments

follows the stated structure

conveys the purpose of each class activity or assignment

completes the scheduled topics

summarizes periodically and at the end of class (or prompts students to do so)

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Presentation Skills

The instructor-educator:

is audible to all students

articulates words so that they are understandable to students, and/or visually represents words that might he difficult for students to hear

varies the tone and pitch of voice for emphasis and interest

speaks at a pace that permits students to understand and take notes

establishes and maintains eye contact

avoids over-reliance on reading content from notes, slides, or texts

avoids distracting mannerisms

uses visual aids effectively (e.g. when appropriate to reinforce a concept, legible handwriting, readable slides)

effectively uses the classroom space

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Clarity

The instructor-educator:

notes new terms or concepts

elaborates or repeats complex information

uses examples to explain content

makes explicit statements drawing student attention to certain ideas

pauses during explanations to ask and answer questions

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Content Knowledge

The instructor-educator:

makes statements that are accurate according to the standards of the field

incorporates current research in the field

identifies sources, perspectives, and authorities in the field

identifies diverse sources, perspectives, and authorities in the field

communicates the reasoning process behind operations and/or concepts

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Instructor-Student Rapport

The instructor-educator:

attends respectfully to student comprehension or puzzlement

invites students’ participation and comments

treats students as individuals (e.g. uses students’ names)

provides periodic feedback

incorporates student ideas into class

uses positive reinforcement (i.e. doesn’t punish or deliberately embarrass students in class)

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

General Peer-Educator Reflection:

What did you observe that went well?

What suggestions for enhancement do you have?

Additional Comments:

[*] Adapted 1/2006 from Chism, N.V.N. (1999) Chapter 6: Classroom Observation, Peer Review of Teaching: A Sourcebook. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing, by Angela R. Linse, Executive Director, Schreyer Institute for Teaching Excellence, Penn State. If you further adapt this form, please include this source citation.

This is a "Checklist" guide, not a scaled rating or evaluation form. This guide is intended to be used as a tool to enable educators… “who teach, supervise and/or support students’ learning to gain feedback from one or more colleagues as part of the process of reflecting on their own practices” (University of Exeter). It asks peer-educators to indicate the presence of teaching activities/behaviors already established as indicative of high-quality teaching. Individual educators, units, departments, etc. can determine which of the items in the categorized lists below reflect their priorities; a targeted set of items per list will make the guide easier for educators to use.

Date:Time: Instructor-educator name:Course #:Course Title:Modality:No. Students:Peer-Educator name:

Peer-educator instructions: Indicate with a check (√) the presence of the following actions and behaviors that indicate high quality teaching. Leave blank items you do not observe. Use N/A if an item is not relevant for this experience or the instructor’s teaching style.

Variety and Pacing of Instruction

The instructor-educator:

uses more than one form of instruction

pauses after asking questions

accepts students’ responses

draws non-participating students into activities/discussions

prevents specific students from dominating activities/discussions

helps students extend their responses

guides the direction of discussion

mediates conflict or differences of opinion

demonstrates active listening

provides explicit directions for active learning tasks (e.g. rationale, duration, product)

allows sufficient time to complete tasks such as group work

specifies how learning tasks will be evaluated (if at all)

provides opportunities and time for students to practice

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Organization

The instructor-educator :

arrives on time

relates this and previous class(es), or provides students with an opportunity to do so

provides class goals or objectives for the class session

provides an outline or organization for the class session

knows how to use the educational technology needed for the class

locates class materials as needed

makes transitional statements between class segments

follows the stated structure

conveys the purpose of each class activity or assignment

completes the scheduled topics

summarizes periodically and at the end of class (or prompts students to do so)

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Presentation Skills

The instructor-educator:

is audible to all students

articulates words so that they are understandable to students, and/or visually represents words that might he difficult for students to hear

varies the tone and pitch of voice for emphasis and interest

speaks at a pace that permits students to understand and take notes

establishes and maintains eye contact

avoids over-reliance on reading content from notes, slides, or texts

avoids distracting mannerisms

uses visual aids effectively (e.g. when appropriate to reinforce a concept, legible handwriting, readable slides)

effectively uses the classroom space

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Clarity

The instructor-educator:

notes new terms or concepts

elaborates or repeats complex information

uses examples to explain content

makes explicit statements drawing student attention to certain ideas

pauses during explanations to ask and answer questions

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Content Knowledge

The instructor-educator:

makes statements that are accurate according to the standards of the field

incorporates current research in the field

identifies sources, perspectives, and authorities in the field

identifies diverse sources, perspectives, and authorities in the field

communicates the reasoning process behind operations and/or concepts

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

Instructor-Student Rapport

The instructor-educator:

attends respectfully to student comprehension or puzzlement

invites students’ participation and comments

treats students as individuals (e.g. uses students’ names)

provides periodic feedback

incorporates student ideas into class

uses positive reinforcement (i.e. doesn’t punish or deliberately embarrass students in class)

Examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors that support the above indications (√):

General Peer-Educator Reflection:

What did you observe that went well?

What suggestions for enhancement do you have?

Additional Comments:

[*] Adapted 1/2006 from Chism, N.V.N. (1999) Chapter 6: Classroom Observation, Peer Review of Teaching: A Sourcebook. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing, by Angela R. Linse, Executive Director, Schreyer Institute for Teaching Excellence, Penn State. If you further adapt this form, please include this source citation.

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide

Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide[*]

This is a "Checklist" guide, not a ...

This is a "Checklist" guide, not a ...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Oct 3, 2022

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Peer-Educator Dialogue Protocol

Peer-Educator Dialogue Protocol

Date:Time:Instructor-Educator:Course Number:Course Title:Modality:# Students Enrolled:# Students Present:Peer-Educator:

This dialogue protocol can be used independently or in conjunction with the Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide. It is important to note that the peer-educator dialogue should be an iterative process of lifelong learning and practice improvement. These are tools aimed at helping educators learn with and from one another. How an instructor-educator utilizes or shares the feedback provided in through this dialogue process is completely up to them.

Before class starts:

Short observations such as: when instructor-educator arrives, what happens (e.g. do they greet students?)? Does class start on time? How many students are present? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Introduction:

Does the instructor-educator give context for today’s lesson/learning experience? (What does this look like?) How does the instructor-educator motivate students? What is student response? Do students arrive late? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Core Learning Experience:

Is there variety and pacing in the planned learning experience(s)? Can/do students ask questions? Is the conversation 2-way/are the students part of the conversation or passive listeners? How are student questions addressed? Is it clear how this material relates to the course? (the field?) What percentage of class time is spent in lecture? What might you say about the instructor-educator’s presentation skills? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Group Activity/Participation:

Are students engaged? How are activities relevant? Are these activities intended to be evaluated? If so, how? What percentage of class time is spent in such activities? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Conclusion:

Did the session seem organized well? Did it end on time? Was there any recap or mention of course goals/objectives? Were diverse examples, resources, perspectives etc. included? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Additional comments/observations:

This document was adapted with permission from 2019 document "AAN Peer Observation Protocol" by Patricia Stewart.Photo by Amy Hirschi on Unsplash

Date:Time:Instructor-Educator:Course Number:Course Title:Modality:# Students Enrolled:# Students Present:Peer-Educator:

This dialogue protocol can be used independently or in conjunction with the Peer-Educator Dialogue Guide. It is important to note that the peer-educator dialogue should be an iterative process of lifelong learning and practice improvement. These are tools aimed at helping educators learn with and from one another. How an instructor-educator utilizes or shares the feedback provided in through this dialogue process is completely up to them.

Before class starts:

Short observations such as: when instructor-educator arrives, what happens (e.g. do they greet students?)? Does class start on time? How many students are present? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Introduction:

Does the instructor-educator give context for today’s lesson/learning experience? (What does this look like?) How does the instructor-educator motivate students? What is student response? Do students arrive late? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Core Learning Experience:

Is there variety and pacing in the planned learning experience(s)? Can/do students ask questions? Is the conversation 2-way/are the students part of the conversation or passive listeners? How are student questions addressed? Is it clear how this material relates to the course? (the field?) What percentage of class time is spent in lecture? What might you say about the instructor-educator’s presentation skills? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Group Activity/Participation:

Are students engaged? How are activities relevant? Are these activities intended to be evaluated? If so, how? What percentage of class time is spent in such activities? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Conclusion:

Did the session seem organized well? Did it end on time? Was there any recap or mention of course goals/objectives? Were diverse examples, resources, perspectives etc. included? Please note examples of instructor-educator actions or behaviors.

Went well:

Consider for enhancement:

Additional comments/observations:

This document was adapted with permission from 2019 document "AAN Peer Observation Protocol" by Patricia Stewart.Photo by Amy Hirschi on Unsplash

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Peer-Educator Dialogue Protocol

Peer-Educator Dialogue Protocol

Date:Time:Instructor-Educator:Cours...

Date:Time:Instructor-Educator:Cours...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Oct 3, 2022

Posted on: Teaching Toolkit Tailgate

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

The Three “P’s” of Academic Integrity

Promote classroom discussions about integrity

Connect academic integrity to the professions

Reaffirm value of honest work

Encourage openness

Clarify terms and expectations

Prevent through assessment design

Consider and honor pledge

Create alternate assignments/tests/quizzes

Assign topics that require analysis not just facts

Establish classroom policy on collaboration

Protect the learning environment

Consistently enforce the university policy

Establish clear grading criteria

Allow reasonable time for assignment completion

Base course grade on multiple assessments

Responding to Academic Misconduct

Discuss the allegation of misconduct with the student

Allow the student to respond to the allegation

Outline the rationale for the penalty, as well as the penalty

Let them know about resources like the University Ombudsperson

Remember to…

Listen respectfully

Work on misperceptions and misunderstandings

Keep emotions in check

Maintain eye contact

Document the conversation

When in doubt…

Contact the Office of the University Ombudsperson at ombud@msu.edu or (517) 353-8830

Connect academic integrity to the professions

Reaffirm value of honest work

Encourage openness

Clarify terms and expectations

Prevent through assessment design

Consider and honor pledge

Create alternate assignments/tests/quizzes

Assign topics that require analysis not just facts

Establish classroom policy on collaboration

Protect the learning environment

Consistently enforce the university policy

Establish clear grading criteria

Allow reasonable time for assignment completion

Base course grade on multiple assessments

Responding to Academic Misconduct

Discuss the allegation of misconduct with the student

Allow the student to respond to the allegation

Outline the rationale for the penalty, as well as the penalty

Let them know about resources like the University Ombudsperson

Remember to…

Listen respectfully

Work on misperceptions and misunderstandings

Keep emotions in check

Maintain eye contact

Document the conversation

When in doubt…

Contact the Office of the University Ombudsperson at ombud@msu.edu or (517) 353-8830

Authored by:

Shannon Burton

Posted on: Teaching Toolkit Tailgate

The Three “P’s” of Academic Integrity

Promote classroom discussions about integrity

Connect academic in...

Connect academic in...

Authored by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Thursday, Jul 30, 2020

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

First things first - put your students to work immediately

The primary goal: students should be working on day one"The First Days of School: How to Be an Effective Teacher" by Harry K. Wong and Rosemary T. Wong is a staple in teacher preparation programs and k-12 districts across the country. It is a comprehensive guide for teachers, particularly those new to the profession, focusing on techniques and strategies to establish effective classroom management from the very beginning of the school year. While the book is primarily focused on K-12 education, it offers principles and strategies that can be effectively adapted and applied to higher education settings. The application of these strategies in a university environment involves recognizing the unique context and needs of adult learners while maintaining the core principles of effective teaching. The book emphasizes the importance of the first days of school in setting the tone for the entire year. It discusses practical methods for creating a positive classroom environment, establishing routines, and building relationships with students. Wong advocates for the idea that effective teaching is not just about subject matter expertise but also involves being an effective manager of the classroom. This management includes clear communication of expectations, consistent procedures, and fostering a sense of respect and responsibility among students.A key theme in Wong's work is the concept of the teacher as a facilitator of learning rather than just a transmitter of knowledge. He suggests that well-organized classrooms with clear rules and procedures enable students to engage more effectively in the learning process. Specifically, he details pre-course and early-course actions that educators can take to help ensure the effective facilitation of learning. Before the Semester1. Course Design and Syllabus Preparation: Develop a detailed syllabus that outlines course objectives, expectations, grading policies, required materials, and a schedule of topics and assignments. Ensure that the syllabus aligns with the learning outcomes and includes policies on attendance, late submissions, academic integrity, and inclusivity. The Teaching Center provides syllabus templates in the semester start-up playlist.2. Learning Environment Setup: If teaching in a physical space, consider the classroom layout and how it can foster interaction and engagement. If teaching ina room you are not familiar with, visit the room before the first day of class to get to know the workings of the classroom technology cart. For online courses, organize the digital learning environment in D2L, ensuring that all resources are accessible and user-friendly. MSU IT offers multiple D2L training resources, also detailed in the semester start-up playlist here.3. Instructional Planning: Plan your lessons for the first few weeks. This includes lecture content, discussion questions, group activities, and any multimedia resources you intend to use. Think about how these align with your course objectives and how they cater to diverse learning styles.4. Communication Channels: Set up and familiarize yourself with the communication platforms you will use, whether it’s email, a learning management system, or online forums. Consider how you will use these tools to communicate with students and facilitate discussions. Consider using the Registrar's Office "email my class" tool for early semester communications.On the First Day1. Welcome and Introduction: Do all you can to arrive early to the classroom. If possible, greet students at the door as they enter. 2. Post the Agenda: Post the day's agenda and key learning outcomes. Make it clear to students what they will do during the class session. If possible, assign seats. This gives students a sense of place in the room and helps reduce students' first day stress.3. Put the Students to Work: The primary goal of the first moments of class is to get students working. Give students a task to complete immediately at the start of class; the task should be relevant to the course content and should yield a tangible deliverable. This will set the tone that the class is a place where things happen, where students work, and where learning is defined by activity. Often this first task involves having students demonstrate their prior knowledge of the course's concepts. 4. Save the Syllabus: The least effective way to spend time on the first day of school is to review the syllabus. Use 50 percent of the first class session for content-specific, important work. Use 40 percent of the time on personal introductions and community building, and use the last 10 percent on policy. Never underestimate the power of a strong start to a semester. Define your semester by spending the first day clearly establishing procedures, setting high expectations, and modelling the value of work. This tone-setting is vital to creating a sustainable culture of learning for the rest of the semester. Photo by Claudio Schwarz on Unsplash

Authored by:

Jeremy Van Hof

Posted on: #iteachmsu

First things first - put your students to work immediately

The primary goal: students should be working on day one"The First D...

Authored by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Tuesday, Jan 9, 2024

Posted on: #iteachmsu

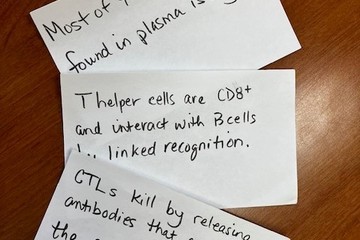

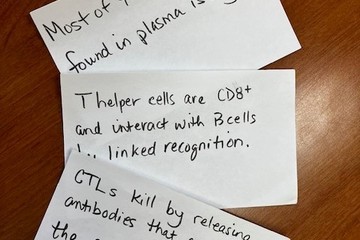

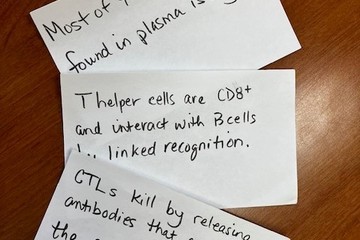

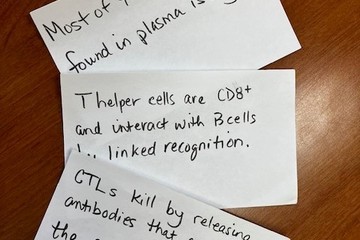

Low Tech Vocab Check

You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.-Inigo Montoya, The Princess Bride

Although that is not the line for which Mandy Patinkin's Inigo is best known, my observations of students in my introductory pathology and molecular diagnostics courses certainly was bringing it to mind more and more often. They were hearing and repeating the right words, but the precise meaning, so important in medicine, was somehow never quite grasped. For reasons I didn't completely understand, what had worked for years wasn't working in my classroom anymore, so I set out to find a practical solution. My first step was discovering reasons for the change. The extended version of that "why" I discovered is material for another whole article. Emphasis on context-based strategies for learning vocabulary in K-12 education, multi-tasking while studying, the effects of reading from screens, not reading at all, decreasing attention spans, and the collective effects of education during the COVID-19 pandemic were all likely contributors to students' "light" understanding of the necessary vocabulary. I was pretty discouraged when I realized that I couldn't change any of those things! However, I wasn't ready to give up, so I started looking in the literature for strategies and solutions. As you might imagine, not a lot has been published about teaching vocabulary to college students, but I did find some ideas when I read about teaching vocabulary to bilingual students and students with learning differences.When you are learning a new language (or struggling with various aspects of accessing your own), you may be missing or misunderstanding the meaning of new words even in context. My students were learning a new language, kind of, as they built their medical vocabulary, weren't they? With that hypothesis in mind, one deceptively simple activity stood out from this research, something known as a "Does it Make Sense" or DIMS activity. Few resources were needed and little prep time. It didn't take a lot of class time to accomplish. It seemed like a low risk place to start.I created my version of a DIMS activity this way. I found about 25 3 x 5 cards moldering in the back of my desk drawer. On them, in bold black marker, I printed short statements about the current unit in pathology. I was teaching immunology, seredipitously the lessons in which learning precise language is most important in the course. The statements I wrote each had an error, a word or two that needed to be changed for the statement to be correct. At the end of a lecture with about 20 minutes of class time left, I pulled out the cards and asked the students to form groups of 4-5. Once the groups were formed, I gave these brief instructions:

Choose one person to read the statement on the card aloud. You may need to read it more than once.

Discuss the statement. Each statement has an error. Determine the error in the statement in your group.

Then decide how to change the statement to make it correct.

When you have your correction ready, raise a hand and I will come and hear your answer. If you get stuck, raise your hand and I will come over and help.

I handed a card to each group, and let the discussions begin. When a group finished and they gave me a correct answer, I gave them another card. Some groups flew through card after card. Others took their time and needed a hint or two to decode their statement. All of the groups had great discussions, and they seemed to stay on task the whole time. In fact, no one, including me, noticed that the activity continued through the end of class and beyond. We had stayed an extra ten minutes when I finally noticed and sent them home! I had one of the best days in the classroom that I had had in a long time. From what I could see as I ran around the room from group to group, most of the students had that "aha" moment that we want for them, the moment they understand and learn something new. What did they learn? Did they learn proper use of every word in the vocabulary of immunology that day? Not at all, but that wasn't the point. The objective was to show them the importance of precise language in medicine and to encourage them to work harder on their own to master the new words in a new context. Based on my observations in class that day and casual student feedback, I think I can say mission accomplished! I plan to expand my use of this type of activity and other low tech approaches in the next few semesters. I want to collect more formal outcomes data and do some actual analysis beyond casual observation. My gut is telling me that I'm on to something. Watch this space for more, and if you are interested, feel free to contact me about collaboration!References:How Grades 4 to 8 Teachers Can Deliver Intensive Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension Interventions to Students With High-Functioning Autism Spectrum DisorderDanielle A. Cravalho, Zaira Jimenez, Aya Shhub, and Michael SolisBeyond Behavior 2020 29:1, 31-41

Although that is not the line for which Mandy Patinkin's Inigo is best known, my observations of students in my introductory pathology and molecular diagnostics courses certainly was bringing it to mind more and more often. They were hearing and repeating the right words, but the precise meaning, so important in medicine, was somehow never quite grasped. For reasons I didn't completely understand, what had worked for years wasn't working in my classroom anymore, so I set out to find a practical solution. My first step was discovering reasons for the change. The extended version of that "why" I discovered is material for another whole article. Emphasis on context-based strategies for learning vocabulary in K-12 education, multi-tasking while studying, the effects of reading from screens, not reading at all, decreasing attention spans, and the collective effects of education during the COVID-19 pandemic were all likely contributors to students' "light" understanding of the necessary vocabulary. I was pretty discouraged when I realized that I couldn't change any of those things! However, I wasn't ready to give up, so I started looking in the literature for strategies and solutions. As you might imagine, not a lot has been published about teaching vocabulary to college students, but I did find some ideas when I read about teaching vocabulary to bilingual students and students with learning differences.When you are learning a new language (or struggling with various aspects of accessing your own), you may be missing or misunderstanding the meaning of new words even in context. My students were learning a new language, kind of, as they built their medical vocabulary, weren't they? With that hypothesis in mind, one deceptively simple activity stood out from this research, something known as a "Does it Make Sense" or DIMS activity. Few resources were needed and little prep time. It didn't take a lot of class time to accomplish. It seemed like a low risk place to start.I created my version of a DIMS activity this way. I found about 25 3 x 5 cards moldering in the back of my desk drawer. On them, in bold black marker, I printed short statements about the current unit in pathology. I was teaching immunology, seredipitously the lessons in which learning precise language is most important in the course. The statements I wrote each had an error, a word or two that needed to be changed for the statement to be correct. At the end of a lecture with about 20 minutes of class time left, I pulled out the cards and asked the students to form groups of 4-5. Once the groups were formed, I gave these brief instructions:

Choose one person to read the statement on the card aloud. You may need to read it more than once.

Discuss the statement. Each statement has an error. Determine the error in the statement in your group.

Then decide how to change the statement to make it correct.

When you have your correction ready, raise a hand and I will come and hear your answer. If you get stuck, raise your hand and I will come over and help.

I handed a card to each group, and let the discussions begin. When a group finished and they gave me a correct answer, I gave them another card. Some groups flew through card after card. Others took their time and needed a hint or two to decode their statement. All of the groups had great discussions, and they seemed to stay on task the whole time. In fact, no one, including me, noticed that the activity continued through the end of class and beyond. We had stayed an extra ten minutes when I finally noticed and sent them home! I had one of the best days in the classroom that I had had in a long time. From what I could see as I ran around the room from group to group, most of the students had that "aha" moment that we want for them, the moment they understand and learn something new. What did they learn? Did they learn proper use of every word in the vocabulary of immunology that day? Not at all, but that wasn't the point. The objective was to show them the importance of precise language in medicine and to encourage them to work harder on their own to master the new words in a new context. Based on my observations in class that day and casual student feedback, I think I can say mission accomplished! I plan to expand my use of this type of activity and other low tech approaches in the next few semesters. I want to collect more formal outcomes data and do some actual analysis beyond casual observation. My gut is telling me that I'm on to something. Watch this space for more, and if you are interested, feel free to contact me about collaboration!References:How Grades 4 to 8 Teachers Can Deliver Intensive Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension Interventions to Students With High-Functioning Autism Spectrum DisorderDanielle A. Cravalho, Zaira Jimenez, Aya Shhub, and Michael SolisBeyond Behavior 2020 29:1, 31-41

Authored by:

Rachel Morris, Biomedical Lab Diagnostics

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Low Tech Vocab Check

You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it...

Authored by:

Monday, Feb 12, 2024

Posted on: Center for Teaching and Learning Innovation

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Syllabus Policy Examples: Attendance

This article provides an overview of example syllabus language for discourse, especially for Fall 2024. This post is the third part of the Civil Discourse in Classrooms series and playlist.

Attendance policies can vary widely for various factors, such as educator values, classroom size, and discipline. MSU does not have a specific attendance policy, but does state:

There is no university-wide regulation requiring class attendance. However, attendance is an essential and intrinsic element of the educational process. In any course in which attendance is necessary to the achievement of a clearly defined set of course objectives, it may be a valid consideration in determining the student's grade. It is the responsibility of the instructor to define the policy for attendance at the beginning of the course.

This statement makes it clear that while attendance is important to learning, there is not a specific policy from the university. However, if an educator wants to have a policy, then they must communicate this at the beginning of the course being sure to be clear how it will factor into grades, if applicable. Below, we will provide various pathway examples of attendance policies that can be adapted to individual educational contexts.

Attendance Policy Unrelated to Grades Example

Reflect: In this example, this educator, who has smaller class sizes without exams, values students’ agency to make their own decisions about attendance to place flexibility with life events. This educator believes that there is a natural consequence built in already if students don’t attend class, which is that they miss content.

Frame: An example framing could be, “Active learning and discussion needs everyone to participate and be present to their capacity. I understand that absences may occur and no excuse notes are needed.”

Set Expectations: An example of setting expectations could be, “Regularly missing class makes it difficult for your own and others’ learning processes.”

Communicate Outcomes: Finally, this policy will end with outcomes, and an example ending could be, “If there’s a regular pattern of absence, we will have a conversation about ways we can better support your learning.”

Attendance Policy Linked to Participation Grade Example

Reflect: In this example, this educator, who has discussion-based classes, values regular attendance because it is integral to everyone’s learning. They also want to build in some flexibility to life events.

Frame: An example framing could be, “Discussion and participation is an integral part of this class. Attendance is recorded for each class session and contributes to the participation component of the final grade.”

Set Expectations: An example of setting expectations could be, “Students may miss 3 class periods without question, and additional absences must be documented and communicated with the instructor as soon as possible. Excused absences with documentation include medical emergencies, family emergencies, religious observances, and university-sanctioned events.”

Communicate Outcomes: Finally, this policy will end with outcomes, and an example ending could be, “Unexcused absences beyond 3 missed class periods will result in no participation points for that day’s class (see grading scheme for more details on final grade calculation).”

Attendance Policy Linked to Final Grades Example

Reflect: In this example, this educator, who has hundreds of students in each class, values regular attendance to ensure students are engaging with the content. They want to make it transparent that they use a systematic attendance recording method.

Frame: An example framing could be, “Attendance is an essential and intrinsic element of the educational process.”

Set Expectations: An example of setting expectations could be, “Students must sit in their assigned seats for each class period. Attendance is recorded within the first five minutes of each class period based on presence in one’s assigned seat. Students must attend at least 90% of class sessions.”

Communicate Outcomes: Finally, this policy will end with outcomes, and an example ending could be, “For students that go below 90% of missed class sessions, there will be a 1% drop to the final grade for each class period below the 90%.”

Continue to read more about in the next article, “Classroom Norms & Disruptions,” or return to the Civil Discourse in the Classroom playlist.

Attendance policies can vary widely for various factors, such as educator values, classroom size, and discipline. MSU does not have a specific attendance policy, but does state:

There is no university-wide regulation requiring class attendance. However, attendance is an essential and intrinsic element of the educational process. In any course in which attendance is necessary to the achievement of a clearly defined set of course objectives, it may be a valid consideration in determining the student's grade. It is the responsibility of the instructor to define the policy for attendance at the beginning of the course.

This statement makes it clear that while attendance is important to learning, there is not a specific policy from the university. However, if an educator wants to have a policy, then they must communicate this at the beginning of the course being sure to be clear how it will factor into grades, if applicable. Below, we will provide various pathway examples of attendance policies that can be adapted to individual educational contexts.

Attendance Policy Unrelated to Grades Example

Reflect: In this example, this educator, who has smaller class sizes without exams, values students’ agency to make their own decisions about attendance to place flexibility with life events. This educator believes that there is a natural consequence built in already if students don’t attend class, which is that they miss content.

Frame: An example framing could be, “Active learning and discussion needs everyone to participate and be present to their capacity. I understand that absences may occur and no excuse notes are needed.”

Set Expectations: An example of setting expectations could be, “Regularly missing class makes it difficult for your own and others’ learning processes.”

Communicate Outcomes: Finally, this policy will end with outcomes, and an example ending could be, “If there’s a regular pattern of absence, we will have a conversation about ways we can better support your learning.”

Attendance Policy Linked to Participation Grade Example

Reflect: In this example, this educator, who has discussion-based classes, values regular attendance because it is integral to everyone’s learning. They also want to build in some flexibility to life events.

Frame: An example framing could be, “Discussion and participation is an integral part of this class. Attendance is recorded for each class session and contributes to the participation component of the final grade.”

Set Expectations: An example of setting expectations could be, “Students may miss 3 class periods without question, and additional absences must be documented and communicated with the instructor as soon as possible. Excused absences with documentation include medical emergencies, family emergencies, religious observances, and university-sanctioned events.”

Communicate Outcomes: Finally, this policy will end with outcomes, and an example ending could be, “Unexcused absences beyond 3 missed class periods will result in no participation points for that day’s class (see grading scheme for more details on final grade calculation).”

Attendance Policy Linked to Final Grades Example

Reflect: In this example, this educator, who has hundreds of students in each class, values regular attendance to ensure students are engaging with the content. They want to make it transparent that they use a systematic attendance recording method.

Frame: An example framing could be, “Attendance is an essential and intrinsic element of the educational process.”

Set Expectations: An example of setting expectations could be, “Students must sit in their assigned seats for each class period. Attendance is recorded within the first five minutes of each class period based on presence in one’s assigned seat. Students must attend at least 90% of class sessions.”

Communicate Outcomes: Finally, this policy will end with outcomes, and an example ending could be, “For students that go below 90% of missed class sessions, there will be a 1% drop to the final grade for each class period below the 90%.”

Continue to read more about in the next article, “Classroom Norms & Disruptions,” or return to the Civil Discourse in the Classroom playlist.

Posted by:

Bethany Meadows

Posted on: Center for Teaching and Learning Innovation

Syllabus Policy Examples: Attendance

This article provides an overview of example syllabus language for ...

Posted by:

NAVIGATING CONTEXT

Tuesday, Aug 13, 2024

Posted on: #iteachmsu

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Spring into Spring: Educator Development Opportunities with CTLI (Jan. & Feb.)

Demystifying [Online] Student Engagement

January 18, 2024, 11 a.m. – 12 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Ashley Moore

Join CTLI Affiliate and Assistant Professor, Dr. Ashley Moore, in a dialogue about common challenges engaging students in an online course setting. We’ll talk about how to set the stage for a warm classroom environment, different ways to check in with students, and pedagogical strategies to get student buy-in for your course—all grounded in humanizing praxis.Learn more and register here

Online Program Director Coffee Hour: Best Practices in course design, QM alignment, and D2L templates

January 18, 2024, 1 – 2 p.m., virtual via ZoomCTLI invites you to join us for the Online Program Directors Coffee Hour session for the month of January. We will be focusing this months discussion on best practices in online course design, alignment with Quality Matters, and D2L course templates available at MSU. Please contact Alicia Jenner (jennera1@msu.edu) for event invitation.

Introduction to Peer Dialogues

January 18, 2024, 2 – 3 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Jay Loftus

Peer dialogue is a structured methodology for observation and feedback. It is intended to be a colleague-to-colleague process to help improve instructional practice, and ultimately student learning experiences and outcomes. Unlike a formal review of instructional practice that may occur as part of tenure and promotion, peer dialogue is a collegial and collaborative practice aimed at improving skills and strategies. In part 1 of peer dialogues participants will learn about the process.Learn more and register here

Using Collaborative Discussion

January 24, 2024, 10 – 11:30 a.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Shannon Burton

CTLI is happy to host MSU's Office of the University Ombudsperson team as they share their expertise through the "2023-24 Conflict in Groups: Pedagogy, Projects and Possibilities" series. Learn more and register here

"Welcome to My Classroom" Series: Pedagogy of Care Panel

January 25, 2024, 10 – 11 a.m., virtual via ZoomMediated by Dr. Makena Neal | Panelists include Dr. Crystal Eustice (CSUS) & Dustin DuFort Petty (BSP)

We're excited to start the new calendar year with a panel of educators discussing the what a "pedagogy of care" means to them and what it looks like in their learning environments.Learn more and register here

Advising/Tutoring Appointment Systems Training

January 25, 2024, 2 – 3 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Katie Peterson and Patrick Beatty

Whether you are a new or current user of the Advising/Tutoring Appointment System, this session will provide guidance on different components of this system, including how to manage appointment availability, adding a student to you or another advisor’s schedule, and additional tips and tricks. Learn more and register here

Book Discussion: “Teaching on days after: educating for equity in the wake of injustice”

January 30, 2024, 1:30 – 3 p.m., virtual via ZoomFacilitated by Drs. Makena Neal and Ashley Moore

For our second discussion, we’ll be reading “Teaching on days after: educating for equity in the wake of injustice" by Alyssa Hadley Dunn (published by Teachers College Press in 2022). This title is available via the MSU Main Library as an eBook (ProQuest EBook Central).Learn more and register here

Boosting student engagement: Easy tactics and tools to connect in any modality

February 5, 2024, 1 – 2 p.m., virtual via ZoomFacilitated by Drs. Ellie Louson and Makena Neal

Using zoom chat, google docs and slides, word clouds, D2L, and other MSU tech tools, we will focus on low-barrier ways that instructors can connect with students, help students connect with each other, organize whole-class or small-group brainstorms, and translate effective in-person activities for hybrid or online classrooms.Learn more and register here

Taking Care of Yourself in Times of Uncertainty

February 8, 2024, 9 – 10 a.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Jaimie Hutshison of the WorkLife Office

We can be creatures of habit. Things that are expected and planned allow us to feel more in control of our lives and our time. This presentation will address best practices for self-care. Learn more and register here

Generative AI Open Office Hours

February 16, 2024, 12 – 1:30 p.m., virtual via ZoomHosted by Dr. Jeremy Van Hof & colleagues from the Enhanced Digitial Learning Initative

This time will be treated like "office hours", where any educator with questions or looking for futher conversation about Generative AI is welcome to join this zoom room whenever suits them!Learn more here

"Welcome to My Classroom" Series: Jessica Sender

February 20, 2024, 1 – 2 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Jessica Sender

This month, we are excited to hear from Jessica Sender, Health Sciences Librarian, Liaison to the College of Nursing, and CTLI Affiliate. Jessica will be showcasing the Anatomage Table (located in the Digital Scholarship Lab on 2West of the Main Library) and the ways it can be incorporated pedagogically to improve learning experiences. Learn more and register here

Dialogue and Deliberation

February 21, 2024, 10 – 11 a.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Shannon Burton

CTLI is happy to host MSU's Office of the University Ombudsperson team as they share their expertise through the "2023-24 Conflict in Groups: Pedagogy, Projects and Possibilities" series. Learn more and register here

January 18, 2024, 11 a.m. – 12 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Ashley Moore

Join CTLI Affiliate and Assistant Professor, Dr. Ashley Moore, in a dialogue about common challenges engaging students in an online course setting. We’ll talk about how to set the stage for a warm classroom environment, different ways to check in with students, and pedagogical strategies to get student buy-in for your course—all grounded in humanizing praxis.Learn more and register here

Online Program Director Coffee Hour: Best Practices in course design, QM alignment, and D2L templates

January 18, 2024, 1 – 2 p.m., virtual via ZoomCTLI invites you to join us for the Online Program Directors Coffee Hour session for the month of January. We will be focusing this months discussion on best practices in online course design, alignment with Quality Matters, and D2L course templates available at MSU. Please contact Alicia Jenner (jennera1@msu.edu) for event invitation.

Introduction to Peer Dialogues

January 18, 2024, 2 – 3 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Jay Loftus

Peer dialogue is a structured methodology for observation and feedback. It is intended to be a colleague-to-colleague process to help improve instructional practice, and ultimately student learning experiences and outcomes. Unlike a formal review of instructional practice that may occur as part of tenure and promotion, peer dialogue is a collegial and collaborative practice aimed at improving skills and strategies. In part 1 of peer dialogues participants will learn about the process.Learn more and register here

Using Collaborative Discussion

January 24, 2024, 10 – 11:30 a.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Shannon Burton

CTLI is happy to host MSU's Office of the University Ombudsperson team as they share their expertise through the "2023-24 Conflict in Groups: Pedagogy, Projects and Possibilities" series. Learn more and register here

"Welcome to My Classroom" Series: Pedagogy of Care Panel

January 25, 2024, 10 – 11 a.m., virtual via ZoomMediated by Dr. Makena Neal | Panelists include Dr. Crystal Eustice (CSUS) & Dustin DuFort Petty (BSP)

We're excited to start the new calendar year with a panel of educators discussing the what a "pedagogy of care" means to them and what it looks like in their learning environments.Learn more and register here

Advising/Tutoring Appointment Systems Training

January 25, 2024, 2 – 3 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Katie Peterson and Patrick Beatty

Whether you are a new or current user of the Advising/Tutoring Appointment System, this session will provide guidance on different components of this system, including how to manage appointment availability, adding a student to you or another advisor’s schedule, and additional tips and tricks. Learn more and register here

Book Discussion: “Teaching on days after: educating for equity in the wake of injustice”

January 30, 2024, 1:30 – 3 p.m., virtual via ZoomFacilitated by Drs. Makena Neal and Ashley Moore

For our second discussion, we’ll be reading “Teaching on days after: educating for equity in the wake of injustice" by Alyssa Hadley Dunn (published by Teachers College Press in 2022). This title is available via the MSU Main Library as an eBook (ProQuest EBook Central).Learn more and register here

Boosting student engagement: Easy tactics and tools to connect in any modality

February 5, 2024, 1 – 2 p.m., virtual via ZoomFacilitated by Drs. Ellie Louson and Makena Neal

Using zoom chat, google docs and slides, word clouds, D2L, and other MSU tech tools, we will focus on low-barrier ways that instructors can connect with students, help students connect with each other, organize whole-class or small-group brainstorms, and translate effective in-person activities for hybrid or online classrooms.Learn more and register here

Taking Care of Yourself in Times of Uncertainty

February 8, 2024, 9 – 10 a.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Jaimie Hutshison of the WorkLife Office

We can be creatures of habit. Things that are expected and planned allow us to feel more in control of our lives and our time. This presentation will address best practices for self-care. Learn more and register here

Generative AI Open Office Hours

February 16, 2024, 12 – 1:30 p.m., virtual via ZoomHosted by Dr. Jeremy Van Hof & colleagues from the Enhanced Digitial Learning Initative

This time will be treated like "office hours", where any educator with questions or looking for futher conversation about Generative AI is welcome to join this zoom room whenever suits them!Learn more here

"Welcome to My Classroom" Series: Jessica Sender

February 20, 2024, 1 – 2 p.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Jessica Sender

This month, we are excited to hear from Jessica Sender, Health Sciences Librarian, Liaison to the College of Nursing, and CTLI Affiliate. Jessica will be showcasing the Anatomage Table (located in the Digital Scholarship Lab on 2West of the Main Library) and the ways it can be incorporated pedagogically to improve learning experiences. Learn more and register here

Dialogue and Deliberation

February 21, 2024, 10 – 11 a.m., virtual via ZoomPresented by Dr. Shannon Burton

CTLI is happy to host MSU's Office of the University Ombudsperson team as they share their expertise through the "2023-24 Conflict in Groups: Pedagogy, Projects and Possibilities" series. Learn more and register here

Posted by:

Makena Neal

Posted on: #iteachmsu

Spring into Spring: Educator Development Opportunities with CTLI (Jan. & Feb.)

Demystifying [Online] Student Engagement

January 18, 2024, 11 a.m. ...

January 18, 2024, 11 a.m. ...

Posted by:

PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

Monday, Jan 8, 2024